Skip to main content

Notes

table of contents

Chapter 2

Benefits Evaluation Framework

Francis Lau, Simon Hagens, Jennifer Zelmer

2.1 Introduction

The Benefits Evaluation (BE) Framework was published in 2006 as the result of a collective effort between

Canada Health Infoway (Infoway) and a group of health informaticians. Infoway

is an independent not-for-profit corporation with the mission to accelerate the

development, adoption and effective use of digital health innovations in

Canada. The health informaticians were a group of researchers and practitioners

known for their work in health information technology (HIT) and health systems data analysis. These individuals were engaged by Infoway to

be members of an expert advisory panel providing input to the pan-Canadian

benefits evaluation program being established by Infoway at the time. The

expert advisory panel consisted of David Bates, Francis Lau, Nikki Shaw, Robyn

Tamblyn, Richard Scott, Michael Wolfson, Anne McFarlane and Doreen Neville.

At the time in Canada, the increased focus on evaluation of eHealth, both

nationally and in the provinces and territories, reflected similar interest

internationally. There was an increasing demand for evidence-informed

investments, for information to drive optimization, and for accountability at

project completion (Hagens, Zelmer, Frazer, Gheorghiu, & Leaver, 2015). The expert advisory panel recognized that a framework was a

necessary step to convert that interest into focused action and results.

The intent of the BE Framework was to provide a high-level conceptual scheme to guide eHealth

evaluation efforts to be undertaken by the respective jurisdictions and

investment programs in Canada. An initial draft of the BE Framework was produced by Francis Lau, Simon Hagens, and Sarah Muttitt in early

2005. It was then reviewed by the expert panel members for feedback. A revised

version of the framework was produced in fall of 2005, and published in Healthcare Quarterly in 2007 (Lau, Hagens, & Muttitt, 2007). Supporting the BE Framework, the expert panel also led the development of a set of indicator

guides for specific technologies and some complementary tools to allow broad

application of the framework. Since its publication, the BE Framework has been applied and adapted by different jurisdictions, organizations

and groups to guide eHealth evaluation initiatives across Canada and elsewhere.

This chapter describes the conceptual foundations of the BE Framework and the six dimensions that made up the framework. We then review the

use of this framework over the years and its implications on eHealth evaluation

for healthcare organizations.

2.2 Conceptual Foundations

The BE Framework is based on earlier work by DeLone and McLean (1992, 2003) in

measuring the success of information systems (IS) in different settings, the systematic review by van der Meijden, Tange,

Troost, and Hasman (2003) on the determinants of success in inpatient clinical

information systems (CIS), and the synthesis of evaluation findings from published systematic reviews in

health information systems (HIS) by Lau (2006) and Lau, Kuziemsky, Price, and Gardner (2010). These published

works are summarized below.

2.2.1 Information Systems Success Model

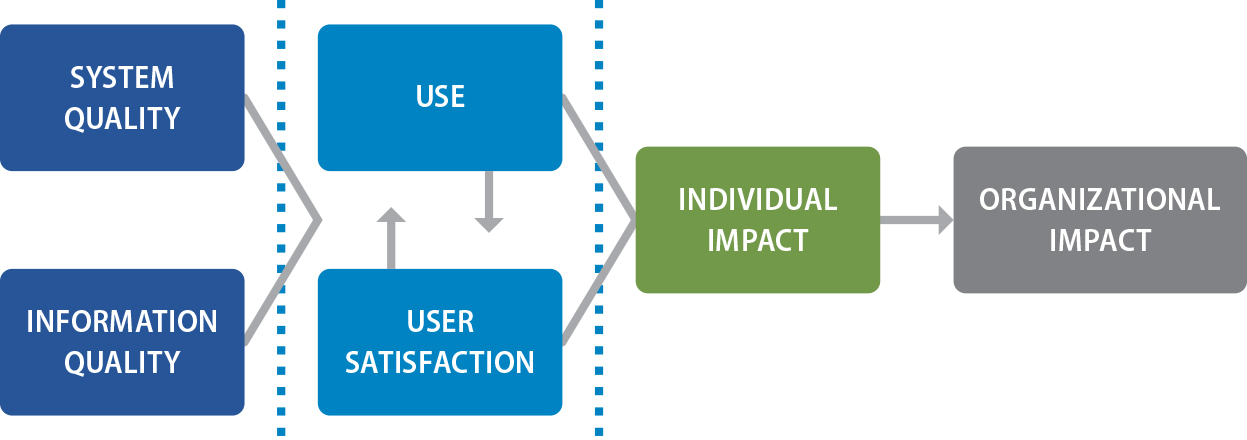

The original IS Success Model published by DeLone and McLean in 1992 was derived from an

analysis of 180 conceptual and empirical IS studies in different field and laboratory settings. The original model has six

dimensions of IS success defined as system quality, information quality, use, user satisfaction,

individual impact, and organizational impact (Figure 2.1). Each of these

dimensions represents a distinct construct of “success” that can be examined by a number of quantitative or qualitative measures.

Examples of these measures for the six IS success dimensions are listed as follows:

- System quality – ease of use; convenience of access; system accuracy and flexibility; response time

- Information quality – accuracy; reliability; relevance; usefulness; understandability; readability

- Use – amount/duration of use; number of inquiries; connection time; number of records accessed

- User satisfaction – overall satisfaction; enjoyment; software and decision-making satisfaction

- Individual impact – accurate interpretation; decision effectiveness, confidence and quality

- Organizational impact – staff and cost reductions; productivity gains; increased revenues and sales

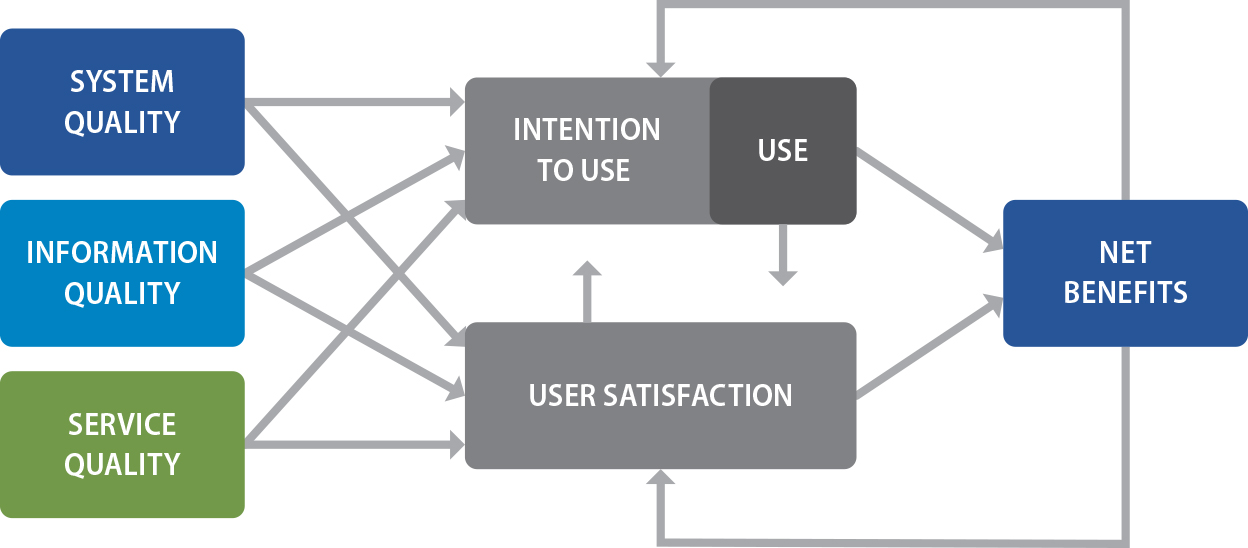

In 2003, DeLone and McLean updated the IS Success Model based on empirical findings from another 285 journal papers and

conference proceedings published between 1992 and 2002 that validated, examined

or cited the original model. In the updated model a service quality dimension

was added, and the individual and organizational impact dimensions were

combined as a single construct called net benefits (Figure 2.2). The addition

of service quality reflected the need for organizations to recognize the

provision of IS service support beyond the technology as a determinant of IS success. Examples of service quality measures are staff reliability, empathy and responsiveness. On the other hand, the net benefits dimension was chosen to simplify the

otherwise increasing number and type of impacts being reported such as group,

industry and societal impacts. Also the inclusion of the word “net” in net benefits was intentional, as it emphasized the overall need to achieve positive impacts that

outweigh any disadvantages in order for the IS to be considered successful.

The IS Success Model by DeLone and McLean is one of the most widely cited conceptual

models that describe the success of IS as a multidimensional construct. It is also one of the few models that have

been empirically validated in numerous independent laboratory and field

evaluation studies across different educational, business and healthcare

settings.

Figure 2.1. IS success model.

Note. From “Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable,” by W. H. DeLone and E. R. McLean, 1992, Information Systems Research, 3(1), p. 87. Copyright 1992 by INFORMS, http://www.informs.org. Reprinted with

permission.

Figure 2.2. Updated IS success model.

Note. From “The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update,” by W. H. DeLone and E. R. McLean, 2003, Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), p. 24. Copyright 2003 by Taylor & Francis. Reprinted with permission.

2.2.2 Clinical Information Systems Success Model

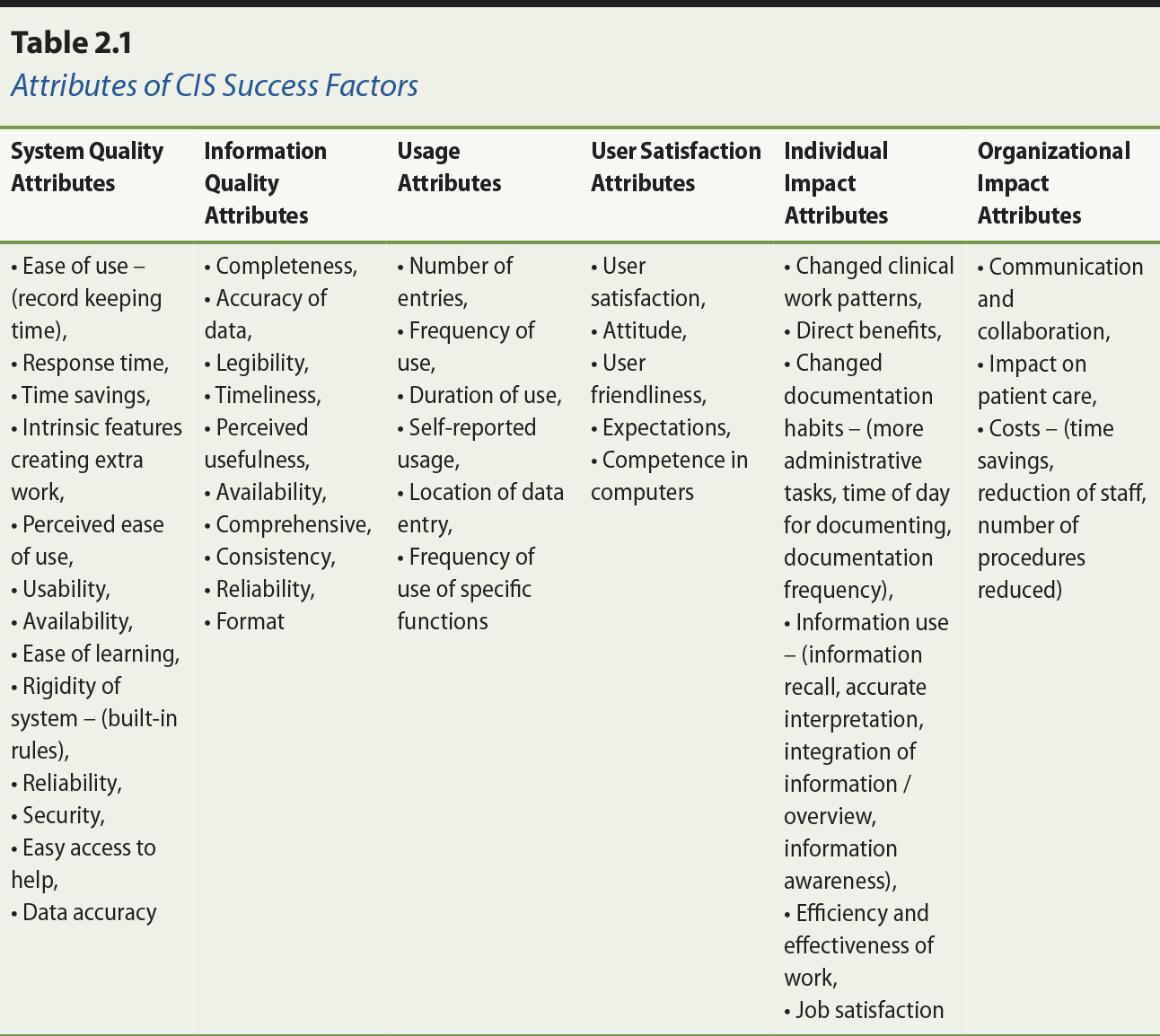

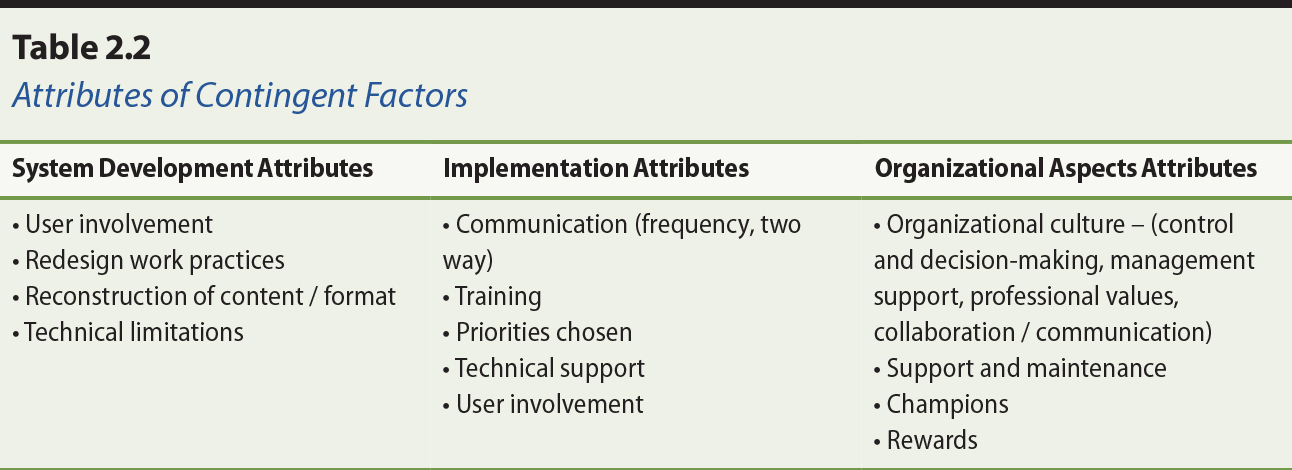

Van der Meijden et al. (2003) conducted a literature review on evaluation

studies published from 1991 to 2001 that identified attributes used to examine

the success of inpatient clinical information systems (CIS). The review used the IS Success Model developed by DeLone and McLean as the framework to determine

whether it could correctly categorize the reported attributes from the

evaluation studies. In total, 33 studies describing 29 different CIS were included in the review, and 50 attributes identified from these studies

were mapped to the six IS success dimensions (Table 2.1). In addition, 16 attributes related to system

development, implementation, and organizational aspects were identified as

contingent factors outside of the six dimensions in the IS Success Model (Table 2.2).

Note. From “Determinants of success of clinical information systems: A literature review,” by M. J. van der Meijden, H. J. Tange, J. Troost, and A. Hasman, 2003, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 10(3), p. 239. Copyright 2003 by Oxford University Press, on behalf of the

American Medical Informatics Association. Adapted with permission.

Note. From “Determinants of success of clinical information systems: A literature review,” by M.J. van der Meijden, H. J. Tange, J. Troost, and A. Hasman, 2003, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 10(3), p. 241. Copyright by Oxford University Press, on behalf of the American

Medical Informatics Association. Adapted with permission.

Since its publication in 2003, the CIS Success Model by van der Meijden and colleagues (2003) has been widely cited

and applied in eHealth evaluation studies. The CIS Success Model can be considered an extension of the original IS Success Model in that it recognizes the influence and importance of contingent

factors related to the system development, implementation and organizational

aspects that were not included in the original model.

2.2.3 Synthesis of Health Information System Reviews

Lau (2006) examined 28 systematic reviews of health information system (HIS) evaluation studies published between 1996 and 2005. From an initial synthesis

on 21 of the published reviews pertaining to clinical information systems/tools

and telehealth/telemedicine evaluation studies, Lau identified 60 empirical

evaluation measures in 20 distinct categories of success factors based on the

six IS success dimensions in the revised DeLone and MacLean model (i.e., system,

information and service quality, use and user satisfaction, and net benefits).

These empirical evaluation measures were reconciled with the success measures

reported in the original and revised DeLone and MacLean models, as well as the

attributes identified in the van der Meijden et al. model. Additional findings

from the Lau review that were supplementary to the BE Framework included the clinical domains, study designs and evaluation measures

used in the evaluation studies. These findings provided an initial empirical

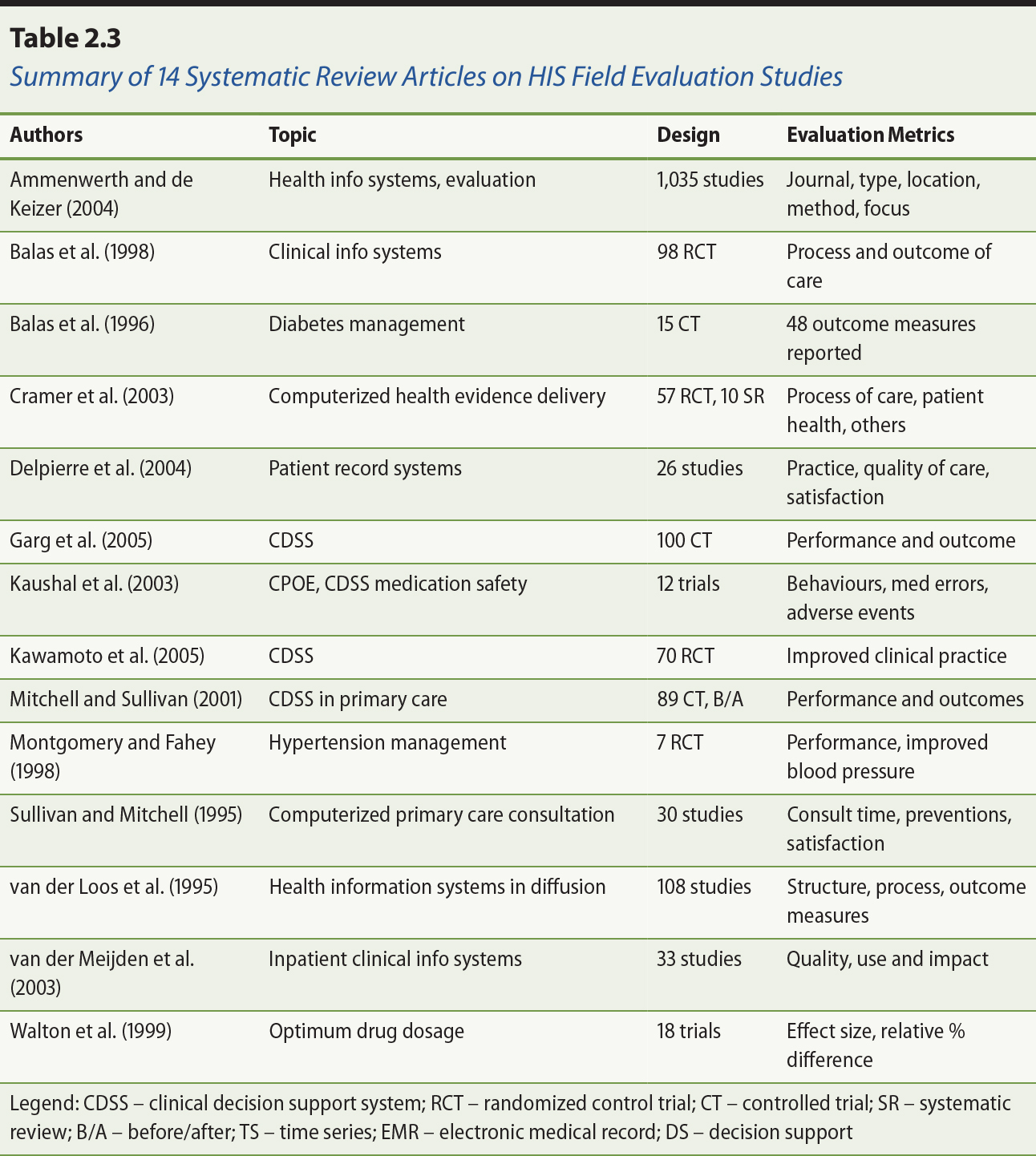

evidence base for the potential application of the BE Framework dimensions, categories and measures (Lau, 2006). Selected findings for

14 of the initial 21 systematic reviews examined are shown in Table 2.3. See

also the separate additional references section for Table 2.3.

Note. From “Increasing the rigor of health information system studies through systematic

reviews,” by F. Lau, 2006, a presentation to 11th International Symposium on Health Information Management Research (iSHIMR), Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

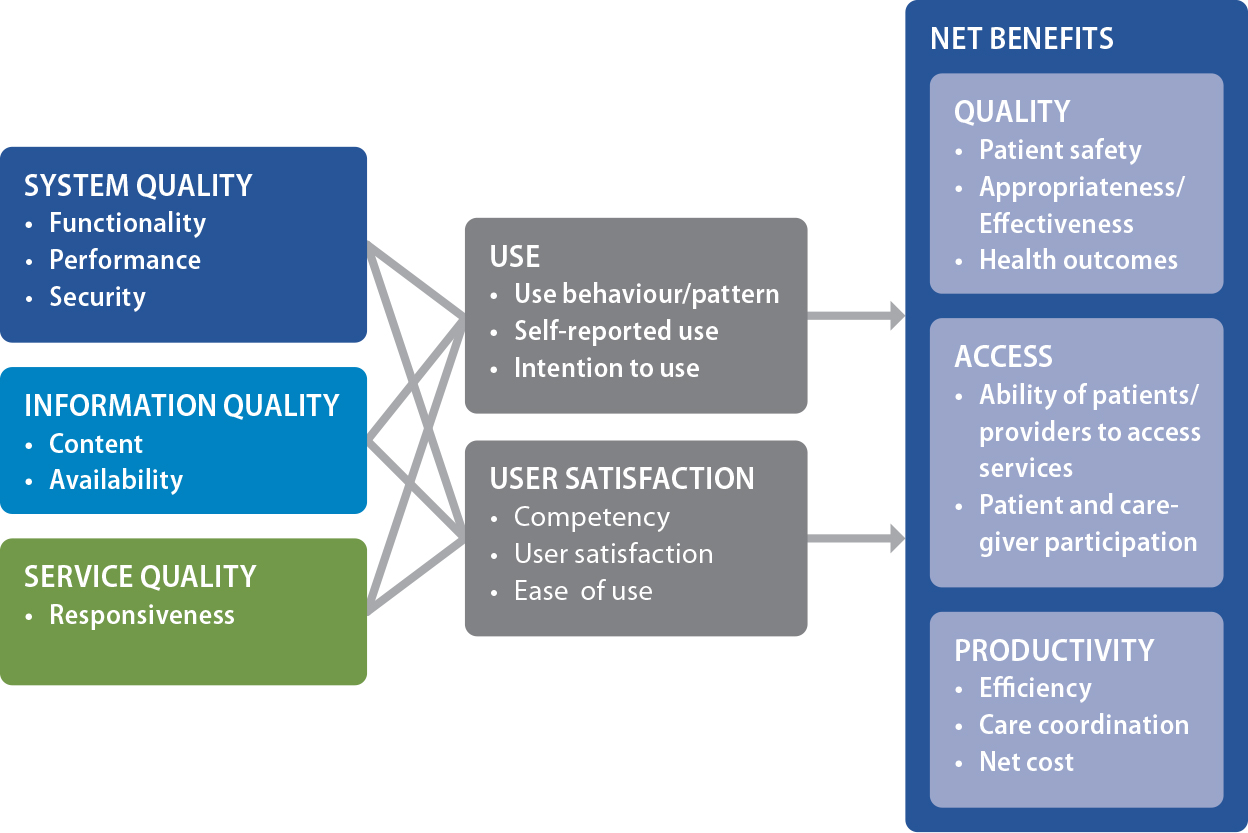

2.3 Benefits Evaluation Framework Dimensions

The BE Framework is based on all six dimensions of the revised DeLone and MacLean IS Success Model, which are system, information and service quality, use and user

satisfaction, and net benefits. A total of 20 categories and 60 subcategories

of evaluation measures are defined in the BE Framework. They are based on the measures identified in the van der Meijden et

al. (2003) CIS Success Model and the Lau et al. (2010) HIS review synthesis. In the BE Framework, the net benefits are further grouped into three subcategories of care

quality, access and productivity. These subcategories are from the original

benefits measurement framework defined by Infoway to determine the impact of

digital health broadly on national healthcare renewal priorities (Infoway,

2005).

When creating the BE Framework, Infoway recognized the importance of organizational and contextual

factors on the adoption and impact of eHealth systems. However, these factors

were considered out-of-scope at the time in order to reduce the complexity of

the framework. The scope was also tailored to increase its acceptance by

stakeholder organizations, as many of the eHealth project teams who would be

overseeing evaluation were not well positioned to investigate and report on the

broader issues. The BE Framework is shown in Figure 2.3. Note that there are other measures in the IS and CIS success models that are not in the BE Framework. They were excluded for such pragmatic reasons as the perceived

subjective nature of the data and the difficulty in their collection.

Figure 2.3. Infoway benefits evaluation (BE) framework.

Note. Copyright 2016 by Canada Health Infoway Inc., http://www.infoway-inforoute.ca.

Reprinted with permission.

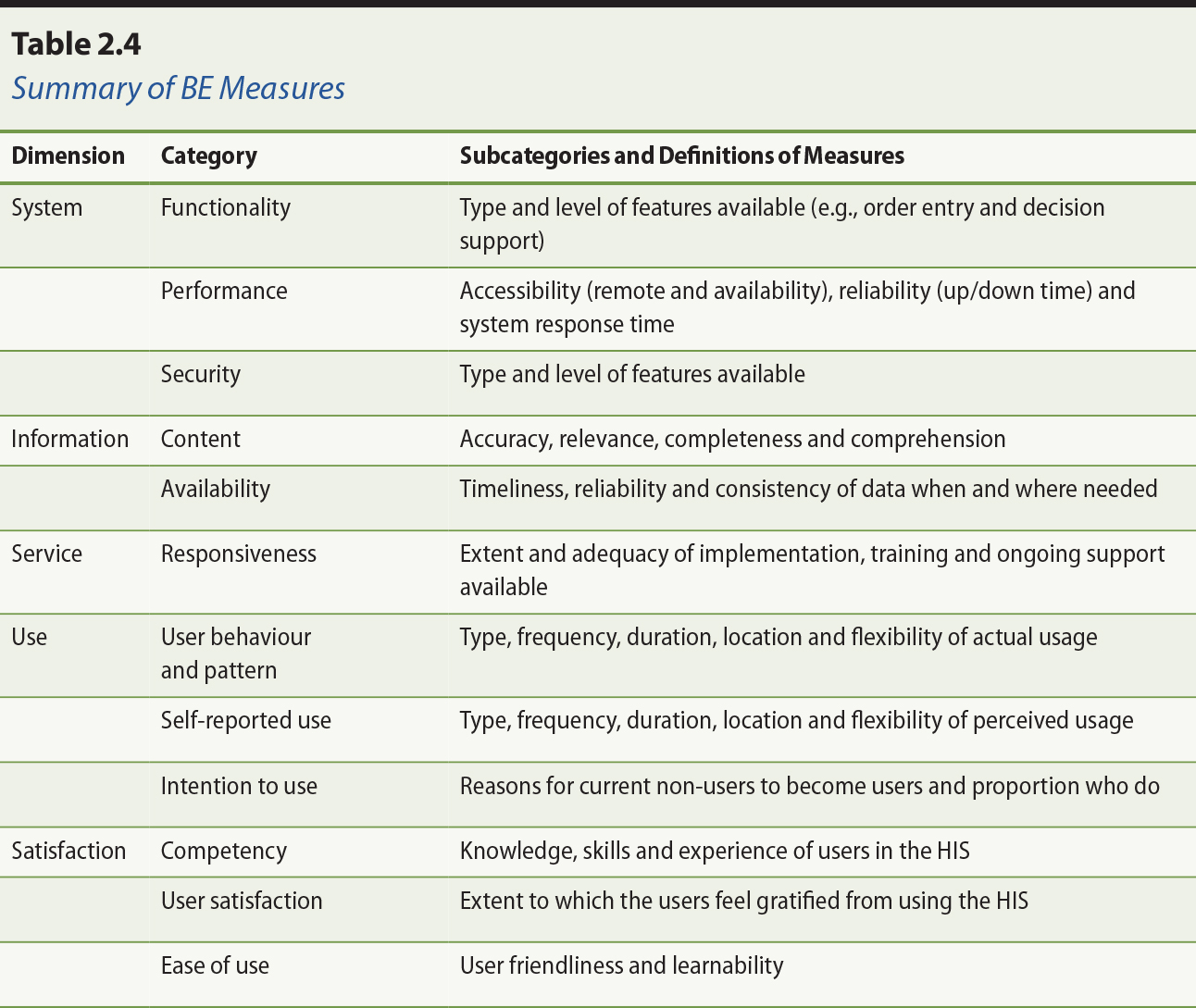

2.3.1 Health Information Technology Quality

There are three HIT quality dimensions, namely system, information, and service.

System quality refers to the technical aspects of the HIT and has three categories of measures on system functionality, performance and

security. Functionality covers the type and level of HIT features present such as order entry with decision support for reminders and

alerts. Performance covers the technical behaviour of the HIT in terms of its accessibility, reliability and response time. Security covers

the ability to protect the integrity and use of the data captured, and to

ensure only authorized access to the HIT.

Information quality refers to the characteristics of the data in the system and has two categories

on the quality of the content and its availability. Content covers the

accuracy, reliability, completeness and comprehension of the data. Availability

covers the timeliness of accessing the data when and where needed.

Service quality refers to HIT implementation, training and ongoing support by staff and has one category on

responsiveness. Examples of responsiveness are the extent and adequacy of user

training and technical support available. Not included are service empathy and

assurance from the IS success model which were considered too subjective to evaluate at that time.

Note that for each of the BE Framework dimensions and categories there are further breakdowns into

subcategories and measures. See section 2.3.4 for a complete list of the

defined HIT quality measures.

2.3.2 Use and User Satisfaction

The use dimension in the BE Framework has three categories which are usage behaviour and pattern,

self-reported use, and intention to use. Usage behaviour and pattern cover

actual HIT usage in terms of type, frequency, duration, location and flexibility. One

example is the volume of medication orders entered by providers on the nursing

units in a given time period. Self-reported use covers perceived HIT usage reported by users in terms of type, frequency, duration, location and

flexibility. Intention to use is the proportion of and factors causing

non-users of an implemented HIT to become active users of the system. The satisfaction dimension has three

categories, namely competency, user satisfaction, and ease of use. Competency

covers the knowledge, skills and experience of the users in the HIT. User satisfaction covers the extent to which the users feel gratified from

using the HIT to accomplish their tasks. Ease of use covers the extent to which the users

feel the HIT is both easy to learn and easy to use.

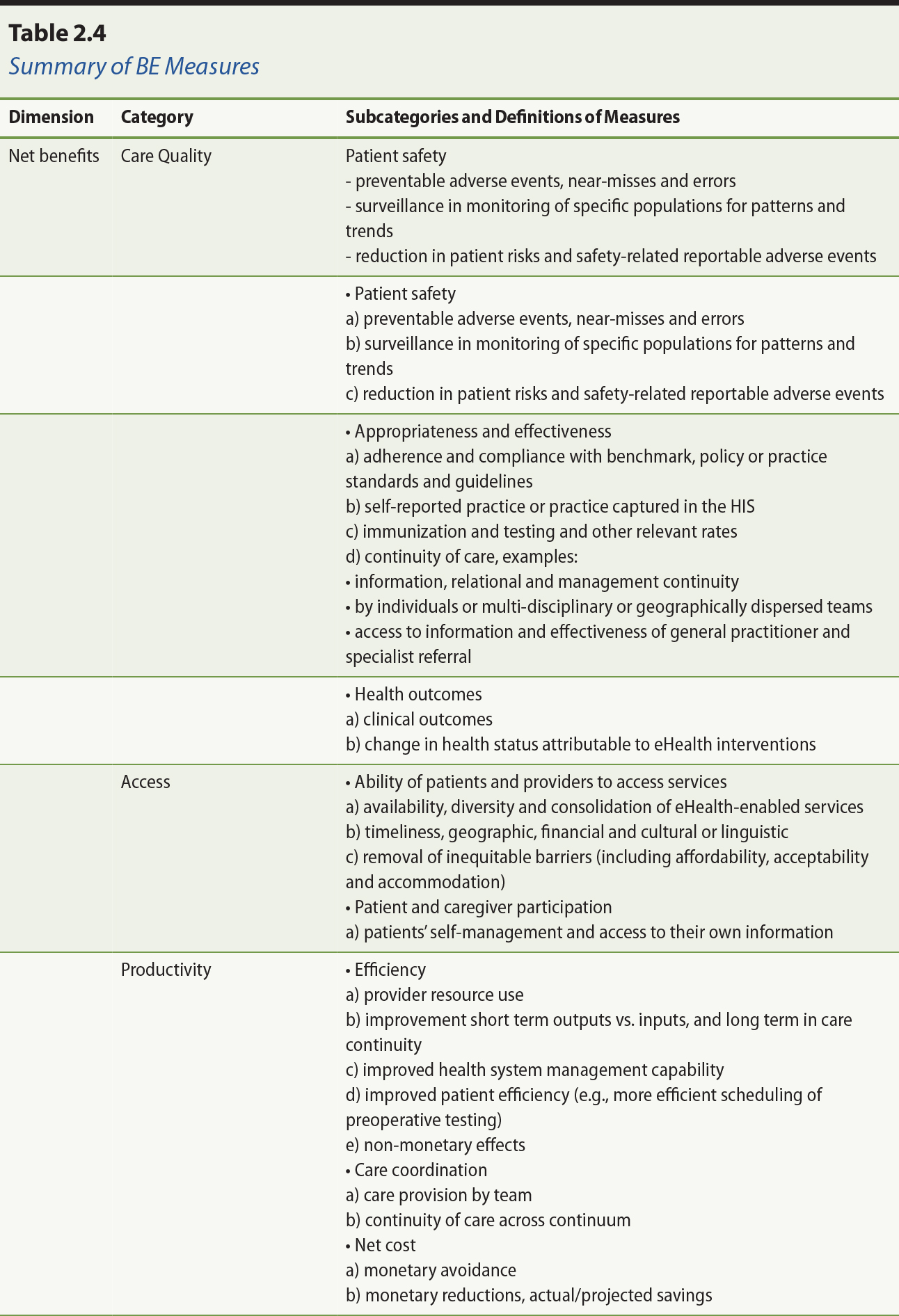

2.3.3 Net Benefits

The net benefits dimension has three categories of measures on care quality,

access and productivity, respectively. Care quality has three subcategories:

patient safety, appropriateness and effectiveness, and health outcomes. Patient

safety includes adverse events, prevention, surveillance, and risk management.

Appropriateness includes the adherence and compliance to benchmarks, policy or

practice standards, and self-reported practices or practice profiles captured

in the system. Effectiveness includes continuity of care with individuals or

local/dispersed teams and referral of services. Health outcomes include short-term

clinical outcomes and longer-term change in the health status of patients

attributable to HIT interventions.

Access has two subcategories that cover the ability of the patient to access

care, which includes enabling access to care through technology (e.g.,

videoconferencing) and driving improvements in access (e.g., wait time

information systems), and the extent of patient/caregiver participation in

these services. Productivity has three subcategories: efficiency, care

coordination, and net cost. Efficiency includes resource use, output and care

continuity improvement, and health systems management capability. Care

coordination includes care provision by teams and continuity of care across

settings. Net cost includes monetary avoidance, reduction and saving.

2.3.4 Summary of Benefit Evaluation Measures

The BE Framework dimensions, categories, subcategories and measures are summarized in

Table 2.4. Note that these are suggested measures only, and are not an

exhaustive list of measures reported in the literature. Healthcare

organizations may choose to adopt these measures or adapt and extend the list

to include new measures to suit their needs.

Note. From “A proposed benefits evaluation framework for health information systems in

Canada,” by F. Lau, S. Hagens, and S. Muttitt, 2007, Healthcare Quarterly, 10(1), p. 115. Copyright 2007 by Longwoods™ Publishing Corp. Reprinted with permission.

2.4 Benefit Evaluation Framework Usage

Since its debut in 2006, the BE Framework has been applied, adapted and cited in different evaluation reports,

reviews, studies and commentaries. In this section we describe the companion

resources that were created along with the framework. Then we summarize

evaluation studies conducted in Canada that applied, adapted and cited the

framework, followed by studies from other countries. Last, we include an

example of a survey tool that can be used to evaluate the adoption of eHealth

systems.

2.4.1 Companion Resources

The BE Framework is helpful in describing factors that influence eHealth success. But

there should also be guidance and resources in place to help practitioners

apply the framework in specific field evaluation studies. Guidance can be in

the form of suggested evaluation questions, methods, designs and measures that

are appropriate for the type of eHealth system and adoption stage involved, as

well as the logistics for collecting and analyzing the data needed in the

study. Another form of guidance required relates to managing evaluation

activities, from structuring stakeholder engagement and gaining buy-in, to

finding skilled evaluators, overseeing studies, and communicating results.

Resources can be in the form of sample evaluation study plans, data collection

tools, best practices in eHealth evaluation, completed evaluation reports and

published peer-reviewed evaluation studies. As part of the initial release of

the BE Framework in 2006, Infoway commissioned leading experts to develop indicator

guides and compiled a BE Indicators Technical Report (Infoway, 2006) and a System and Use Assessment (SUA) survey tool (Infoway, 2006) as two companion resources. These resources were

developed in collaboration with the Infoway BE expert advisory panel, eight subject matter experts, and two consultant teams.

The 2006 BE Indicators Technical Report (Infoway, 2006) includes a detailed description of

the BE Framework, suggested evaluation questions, indicators and measures for specific

eHealth programs, criteria for selecting appropriate BE indicators, and examples of tools and methods used in completed evaluation

studies. The report covers six program areas, which are diagnostic imaging,

drug information systems, laboratory information systems, public health

systems, interoperable Electronic Health Records (iEHRs) and telehealth. These were some of the core initial investment programs

funded by Infoway where it was necessary to assess tangible benefits to the

jurisdictions and healthcare organizations as co-funders of these programs.

Version 2.0 of the BE Indicators Technical Report was released in 2012 with expanded content

(Infoway, 2012). The report still covers six program areas but laboratory

information system has been merged with interoperable EHR as one section, and electronic medical records (EMR) for physician/nurse practitioner offices has been added as a new section. In

Version 2.0 there are many more examples of published evaluation studies

including those from Canadian jurisdictions and healthcare organizations. A BE planning template has also been added to facilitate the creation of a practical

evaluation plan for any eHealth system, and provide some of the practical

guidance on managing evaluation activities. Since the publication of Version

2.0, additional program indicator sets and tools have been developed for

telepathology, consumer health solutions and ambulatory EMR.

The SUA survey tool was introduced in 2006 as a multipart semi-structured questionnaire to collect

information from users on the quality of the eHealth system and its usage in

the organization. The questionnaire has since been adopted as a standardized

Infoway survey tool to collect comparable information on the quality and use of

eHealth systems being evaluated in Canada (Infoway, 2012). The SUA survey tool is aligned with the HIT quality, use and satisfaction dimensions of the BE Framework in terms of the questions used. The current version of this survey

tool has eight sections of questions and guidance on how to administer the

survey and analyze the results for reporting. These sections are on overall

user satisfaction, system quality, information quality, service quality, public

health surveillance, system usage, other comments, and demographic information.

The survey can be adapted or expanded to include specific questions tailored to

a particular eHealth system, such as the perceived accuracy of the images from

the diagnostic imaging system being evaluated (Infoway, 2012).

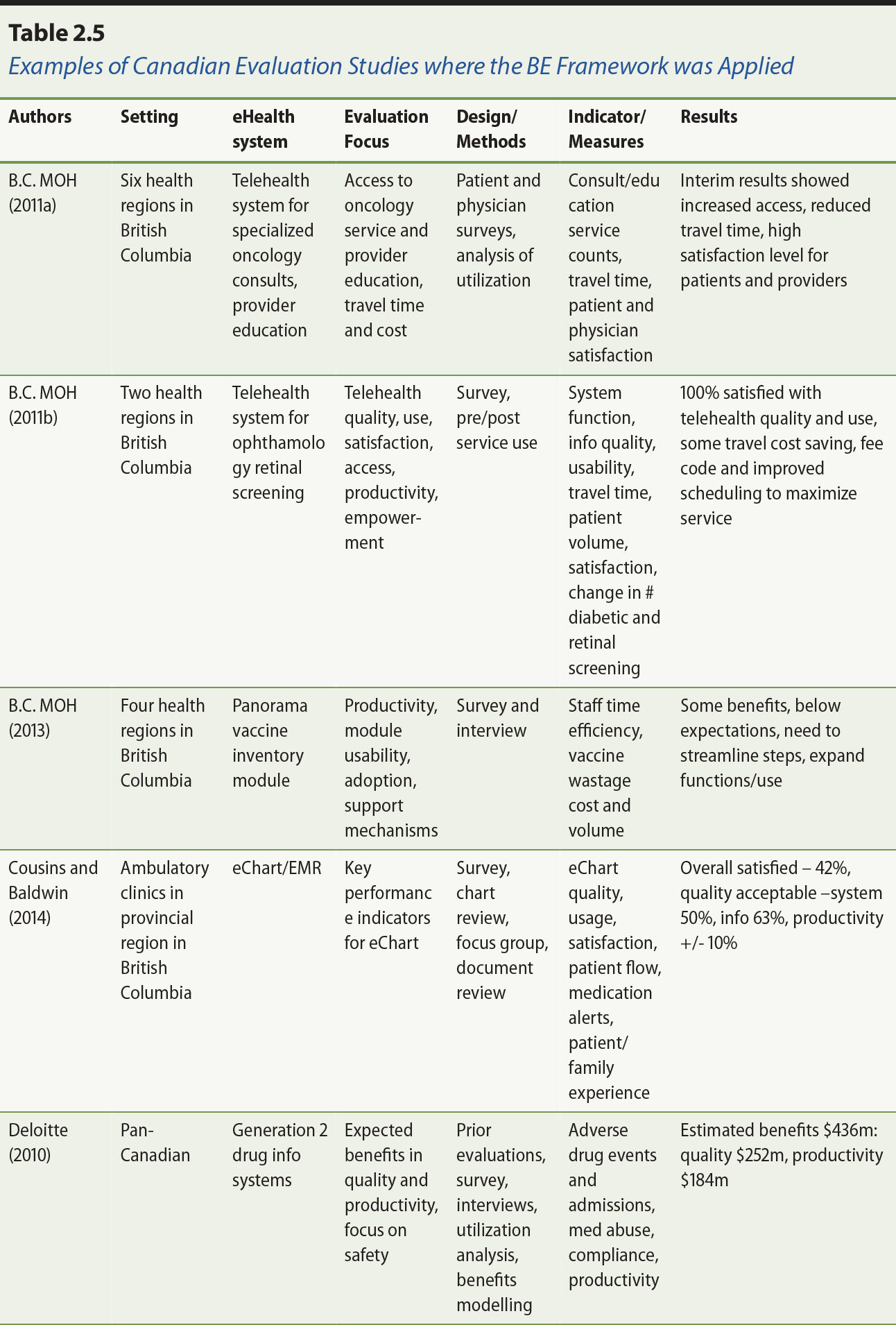

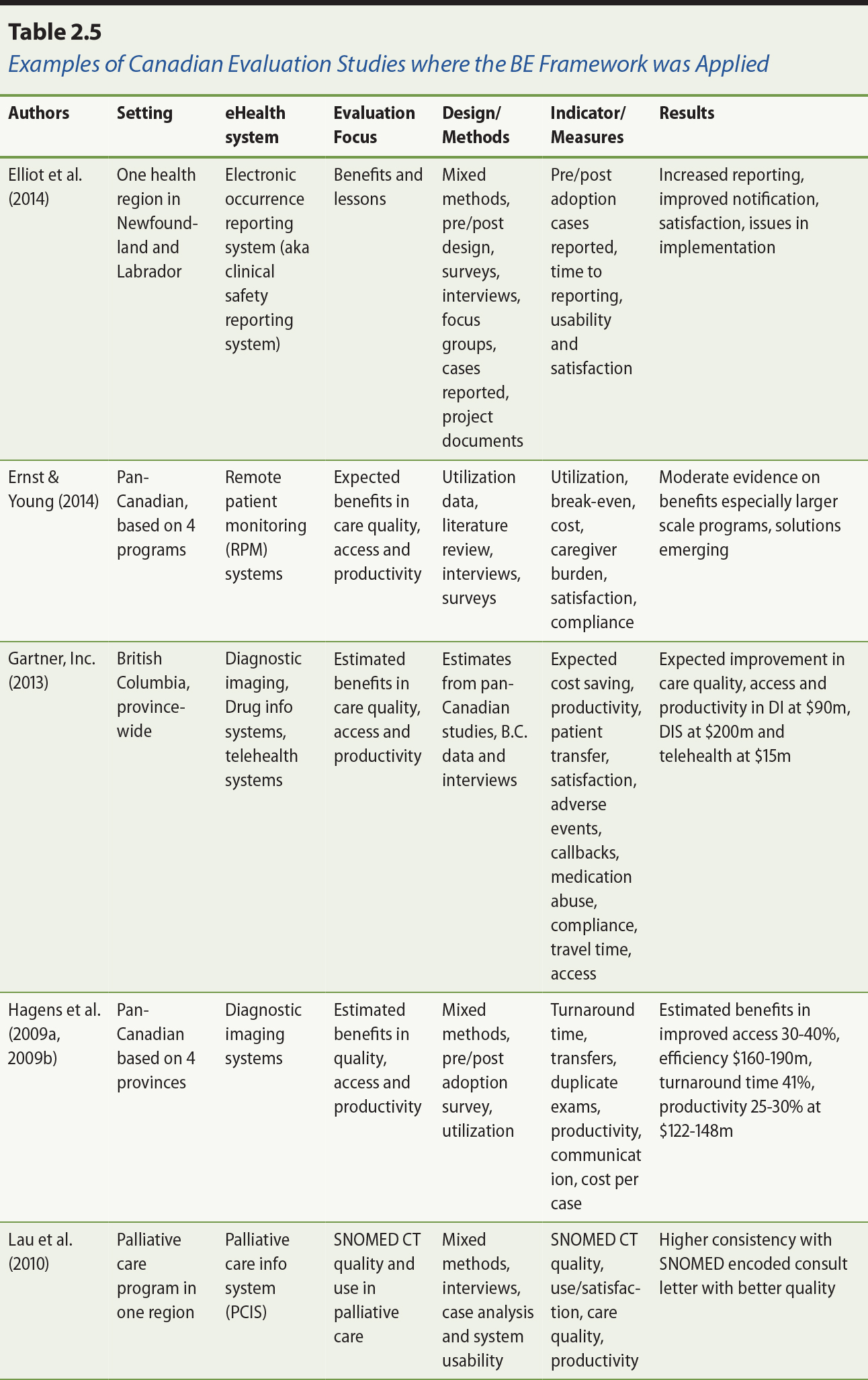

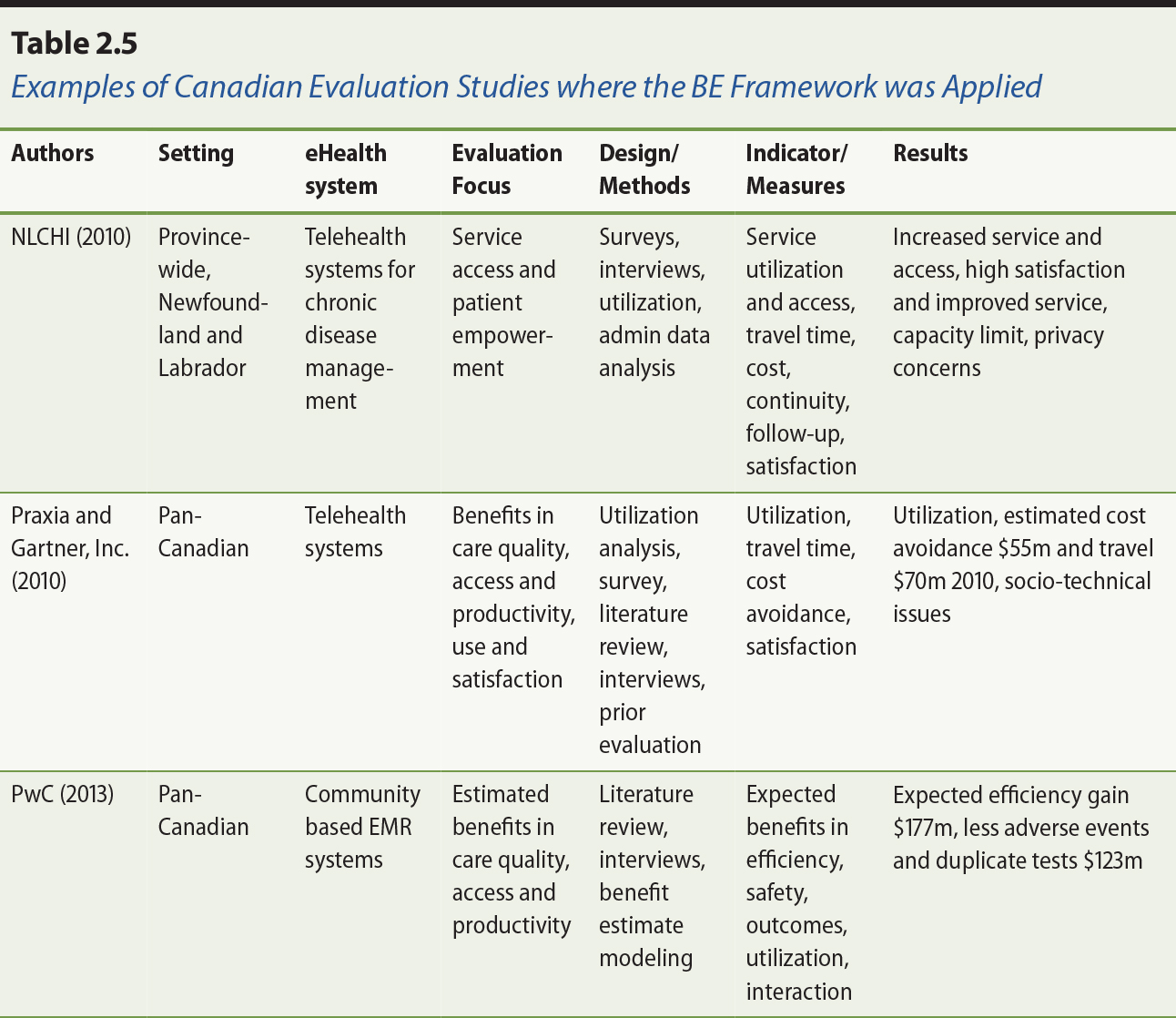

2.4.2 Benefit Evaluation Framework Usage in Canada

Over the years, the BE Framework has been applied in over 50 evaluation studies across Canada. As

examples, Table 2.5 shows 13 Canadian evaluation studies conducted over the

past six years. See also the separate additional references section for Table

2.5. Six of these studies were related to telehealth, covering such clinical

areas as ophthalmology, oncology and chronic disease management (British

Columbia Ministry of Health [MOH], 2011a; B.C. MOH, 2011b; Gartner Inc., 2013; Praxia Information Intelligence & Gartner, Inc., 2010; Ernst & Young, 2014; Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information [NLCHI], 2010). Two studies covered drug information systems (Deloitte, 2010; Gartner

Inc., 2013). Two studies covered diagnostic imaging systems (Gartner Inc.,

2013; Hagens et al., 2009a). Two studies were on EMR systems for ambulatory and community care settings, respectively

(PricewaterhouseCoopers [PwC], 2013; MOH, 2014). There was also one study each on vaccine inventory management (B.C. MOH, 2013), electronic occurrence reporting for patient safety (Elliot, 2014) and SNOMED (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine) Clinical Terms (CT)1 use in palliative care (Lau, 2010).

Most of these evaluation studies focused on satisfaction, care quality,

productivity and access dimensions of the BE Framework, with the addition of measures specific to eHealth systems as needed.

Examples include turnaround time for imaging test results, patient travel time

and cost, and SNOMED CT term coverage in palliative care. Most studies used mixed methods to collect and

analyse data from multiple sources. Reported methods include survey, interview,

literature review, service data analysis and modelling of benefit estimates.

Reported data sources include provider and patient surveys, interview and focus

group data, service utilization data, prior evaluation reports and published

peer-reviewed evaluation studies and systematic reviews. Note that many of the

evaluation studies were based on perceived benefits from providers and

patients, or projected benefits based on model cost estimates.

The BE Framework has also been cited in a number of Canadian evaluation studies,

commentaries and student reports. For instance, in their evaluation of a

provincial drug information system, Mensink and Paterson (2010) adapted the use

and satisfaction dimensions of the BE Framework to examine its adoption and evolution over time. Similarly Shachak et

al. (2013) extended the HIT service quality dimension to include different end user support themes such as

onsite technical and data quality support by knowledgeable staff. In their

commentary on EHR success strategy, Nagle and Catford (2008) emphasized the need to incorporate

benefits evaluation as a key component toward EHR success. O’Grady and colleagues (2009) discussed collaborative interactive adaptive

technologies (e.g., social media). Six graduate-level theses that drew on the BE Framework have also been published. These include the evaluation studies on: a

scanning digital prescriber order system by Alsharif (2012); end user support

for EMR by Dow (2012); electronic occurrence reporting on patient safety by Elliot

(2010); EMR implementation in an ambulatory clinic (Forland, 2008); a multidisciplinary

cancer conferencing system detailed by Ghaznavi (2012); and characteristics of

health information exchanges in literature (Ng, 2012).

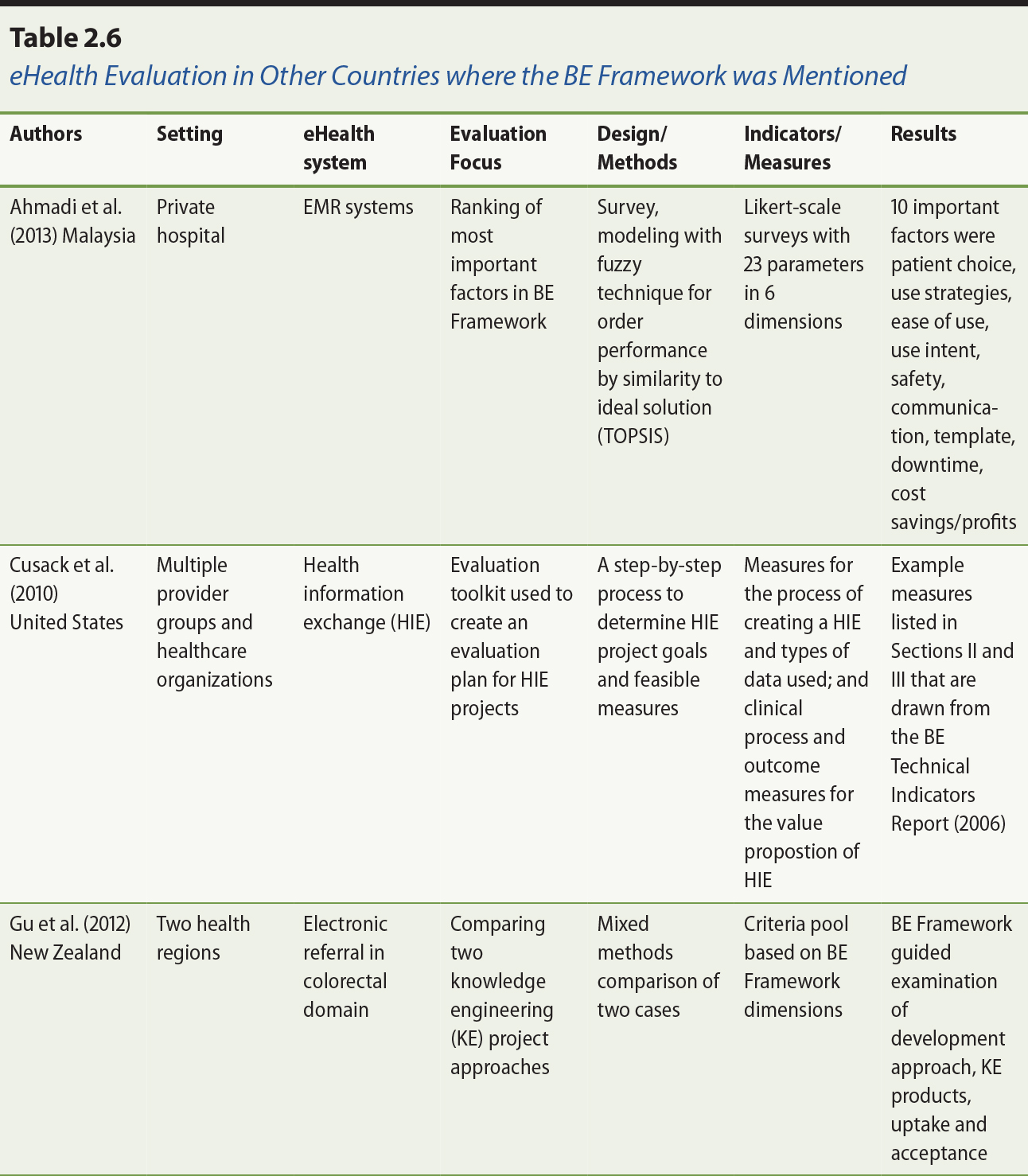

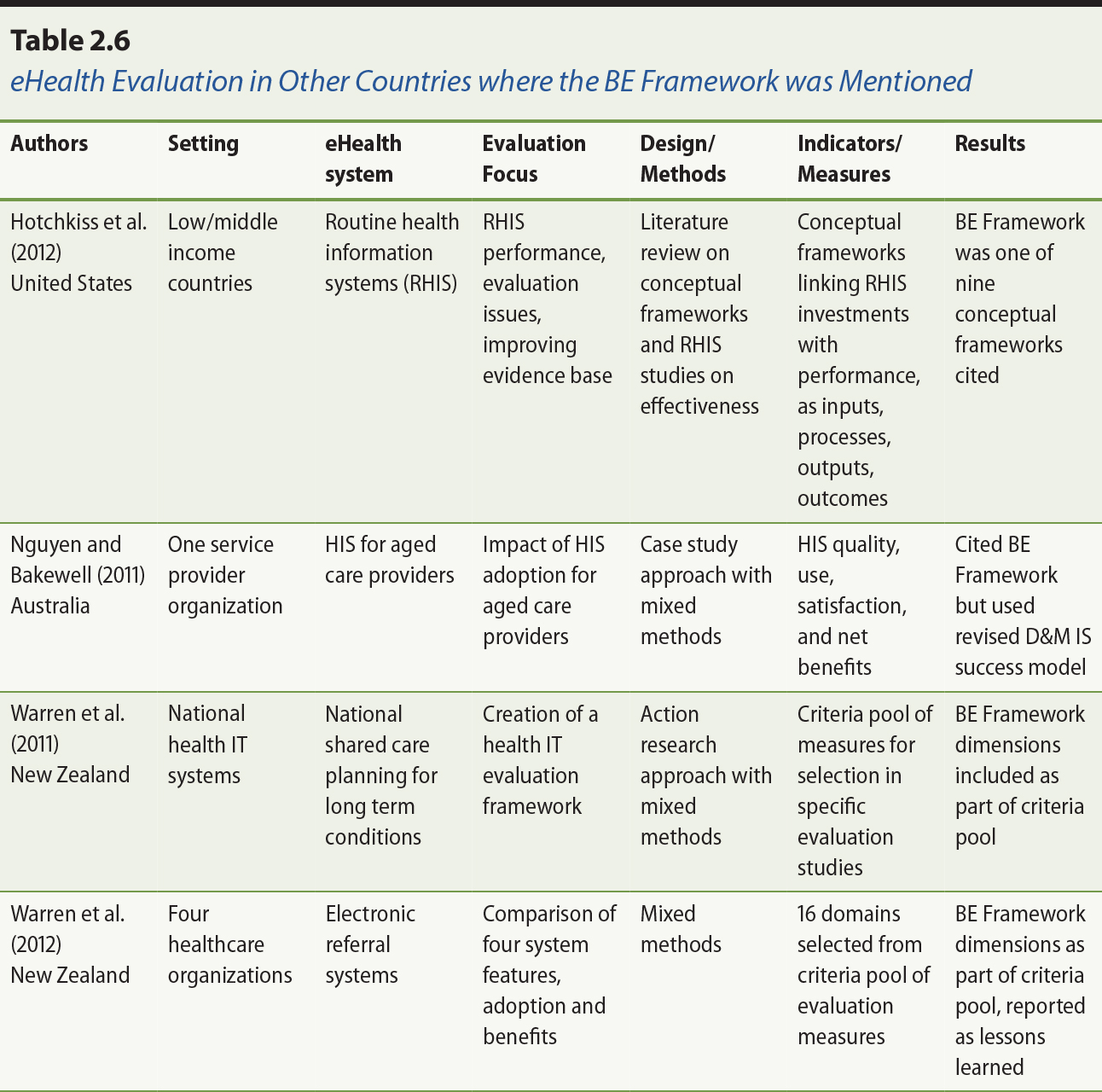

2.4.3 Benefit Evaluation Framework Usage in Other Countries

The BE Framework has also been adapted or cited by health informaticians from other

countries in their eHealth evaluation work. In New Zealand, for example,

Warren, Pollock, Day, Gu, and White (2011) and Warren, Gu, Day, and Pollock

(2012) have incorporated the BE Framework as part of their standardized criteria pool of evaluation measures to

be used selectively when evaluating eHealth systems. The criteria pool covers

work and communication patterns, organizational culture, safety and quality,

clinical effectiveness, IT system integrity, usability, vendor factors, project management, participant

experience, and leadership and governance. Warren and colleagues advocated the

use of action research to conduct evaluation based on a select set of

evaluation measures from the criteria pool. This approach has been applied

successfully in the evaluation of electronic referral systems (Gu, Warren, Day,

Pollock, & White, 2012; Warren et al., 2012).

In their literature review of routine health information systems (RHIS) in low- and middle-income countries, Hotchkiss, Dianna, and Foreit (2012)

examined nine conceptual frameworks including the BE Framework for adaptation to evaluate the performance of RHIS and their impact on health system functioning. Ahmadi, Rad, Nilashi, Ibrahim,

and Almaee (2013) applied a fuzzy model called Technique for Order Performance

by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) to identify the 10 most important factors in hospital EMR adoption based on 23 factors derived from the BE Framework. In addition, the evaluation toolkit for health information exchange

projects from the United States Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

references a number of the measures from the BE Indicators Technical Report (Infoway, 2006) as recommendations for U.S. health information exchange projects (Cusack, Hook, McGowan, Poon, & Atif, 2010). A summary on the use of the BE Framework by these authors is shown in Table 2.6. See also the separate

additional references section for Table 2.6.

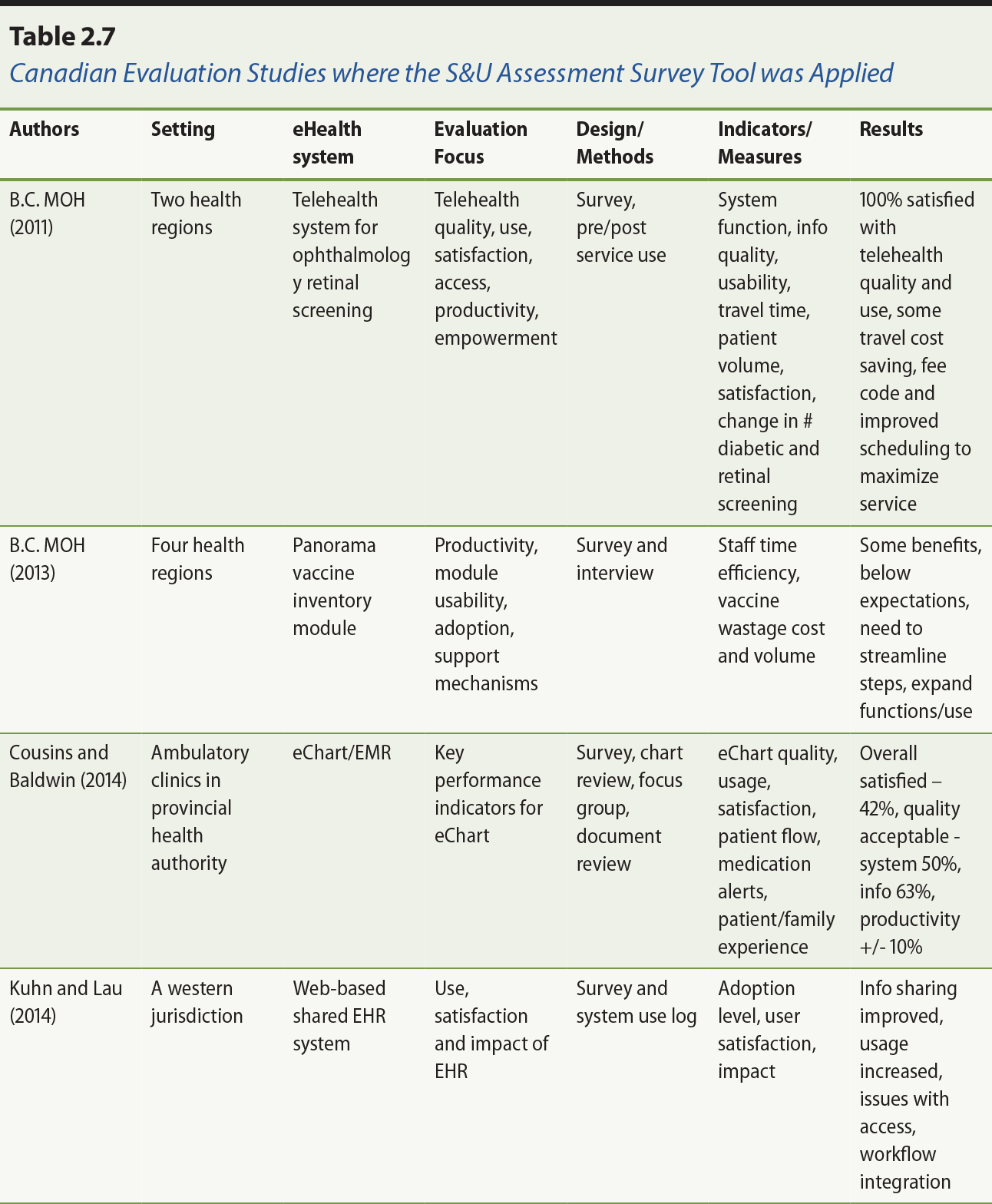

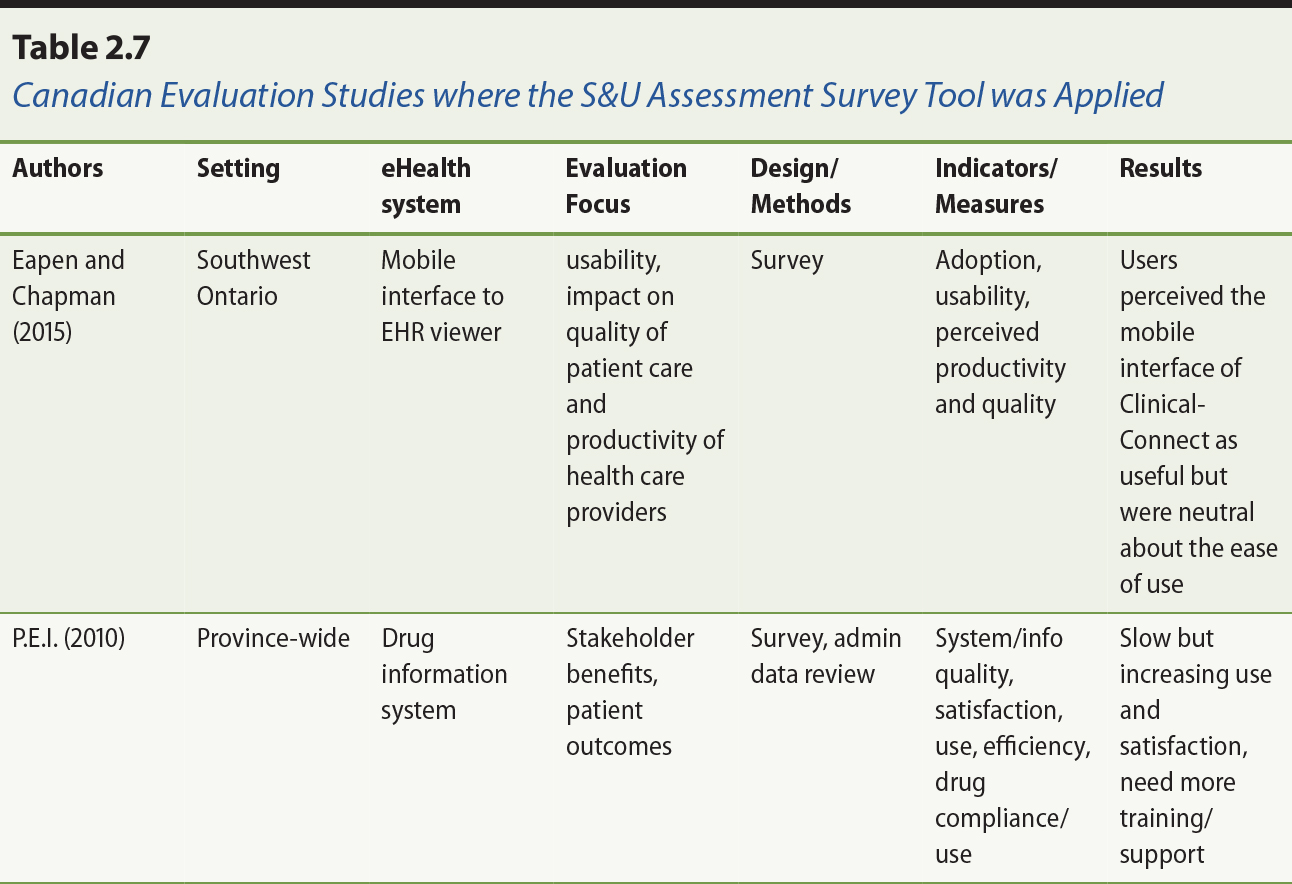

2.4.4 System and Use Assessment Survey Tool Usage

The System and Use Assessment (SUA) survey tool has been applied in different eHealth evaluation studies across

Canada. Recent examples include the evaluation of teleophthalmology and vaccine

inventory management systems (Ministry of Health [MOH], 2011, 2013) and eChart (Cousins & Baldwin, 2014) in British Columbia, shared EHR in a western jurisdiction (Kuhn & Lau, 2014), and the drug information system in Prince Edward Island (Prince

Edward Island [P.E.I.], 2010). A summary of these evaluation studies and how the survey tool was

applied is shown in Table 2.7. See also the separate additional references

section for Table 2.7.

There are also evaluation studies where the SUA survey has been adapted or cited. For instance, one Canadian jurisdiction – Nova Scotia – adapted the SUA survey tool to include more specific questions in the evaluation of their

interoperable EHR picture archival and communication (PAC) and diagnostic imaging (DI) systems (for details, see Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health

Information [NLCHI], 2014). Many of these studies are also available on the Canada Health Infoway

website. Other Canadian researchers adapted the survey tool to examine the

quality and use of physician office EMRs (Paterson et al., 2010). In the United States, Steis et al. (2012) adapted the

survey tool to examine user satisfaction with an electronic dementia assessment

tool. In Saudi Arabia, Bah et al. (2011) adapted the tool to determine the

level and extent of EHR adoption in government hospitals.

2.5 Implications

The BE Framework has proved to be a helpful conceptual scheme in describing and

understanding eHealth evaluation. The BE Indicators Report and the SUA survey tool have become useful resources for healthcare organizations to plan

and conduct evaluation studies on specific eHealth systems. The published

evaluation studies that incorporated the BE Framework have provided a growing empirical evidence base where such studies

can be reported, compared and aggregated over time. That said, there are both

conceptual and practical implications with the BE Framework that should be considered. These implications are described below.

2.5.1 Conceptual Implications

There are conceptual implications related to the BE Framework in terms of its scope, definition and perspective. For scope, the BE Framework has purposely excluded organizational and contextual factors to be

manageable. Note that the IS success model by DeLone and McLean (1992, 2003) has also made no mention of

organizational and contextual factors. There was an assumption in that work

that the IS involved were mature and operational systems with a stable user base, which

made adoption issues less central. Yet many healthcare organizations are

continuing to adopt and/or adapt eHealth systems due to changing legislation,

strategies and technologies. As such, organizational and contextual factors can

have a great deal of influence on the success of these eHealth systems. This

limitation is evident from the contingent factors identified in the CIS review by van der Meijden et al. (2003) and in the published evaluation studies

from Canada and elsewhere.

This gap was one of the drivers for the development of the complementary

National Change Management (CM) Framework (Infoway, 2012). Infoway facilitated the development of this

framework though the pan-Canadian Change Management Network, with the intent of

providing projects with practical tools to successfully implement eHealth

change. Measurement is at the centre of the framework, surrounded by governance

and leadership, stakeholder engagement, communications, training and workflow

analysis and integration. Infoway has encouraged the use of the BE and CM frameworks in concert.

For definition, while the BE Framework dimensions, categories and measures have been established from

empirical evidence over time, they are still concepts that can be interpreted

differently based on one’s experience and understanding of the meaning of these terms. In addition, the

evaluation measures in the BE Framework are not exhaustive in what can be measured when evaluating the

adoption and impact of myriad eHealth systems in different healthcare settings.

As such, the caveat is that the definition of concepts and measures can affect

one’s ability to capture key aspects of specific eHealth systems for reporting,

comparison and aggregation as part of the growing eHealth evidence base.

For perspective, it should be made clear that benefits evaluation and eHealth

success are concepts that are dependent on the views and intentions of the

stakeholders involved. There are many questions concerning what is considered “success” including: Who defines success? Who benefits from success? What is the

trade-off to achieve success? These are questions that need to be addressed

early when planning the eHealth system and throughout its design,

implementation and evaluation stages. In short, the BE Framework can be perceived differently according to the various perspectives of

stakeholders.

2.5.2 Practical Implications

There are also practical implications with the BE Framework in terms of how it is applied in real-life settings. One question

raised frequently is how one should apply the framework when planning an

evaluation study in an organization. To do so, one needs to consider the intent

of the evaluation with respect to its focus, feasibility and utility.

For focus, one should identify the most important questions to be addressed and

prioritize them accordingly in the evaluation. The BE Framework has a rich set of measures covering different aspects of eHealth

adoption and impact, but one should not attempt to include all of them within a

single study. For instance, if the focus of a study is to demonstrate the

ability of an eHealth system to reduce medication errors, then one should

select only a few key patient safety measures such as the incidents of adverse

drug events reported over two or more time periods for comparison.

For feasibility, one should determine the availability of the data for the

measures needed in the evaluation, as well as the time, resources and expertise

available to design the study, collect and analyze the data, and report on the

findings. For example, randomized controlled trials are often considered the

gold standard in evaluating healthcare interventions. Yet it may be infeasible

for the organization that is implementing an eHealth system to conduct such a

trial since it is still adjusting to the changes taking place with the system.

Similarly, an organization may not have the baseline data needed or the

expertise available to conduct evaluation studies. In these situations the

organization has to decide how feasible it is to capture the data or acquire

the expertise needed. Capacity to conduct evaluation is another feasibility

consideration, as more complex evaluations may require specialized skill sets

of evaluators, funding, leadership support or other inputs that are limiting

factors for some organizations.

For utility, one needs to determine the extent to which the evaluation efforts

and results can inform and influence change and be leveraged for added value.

The planning and conduct of an evaluation study can be a major undertaking

within an organization. Executive and staff commitment is necessary to ensure

the results and issues arising from the study are addressed to reap the

benefits to the system. To maximize the utility of an evaluation study and its

findings, one should systematically document the effort and results in ways

that allow its comparison with studies from other organizations, and

aggregation as part of the evolving empirical evidence base.

2.6 Summary

This chapter described the BE Framework as a conceptual scheme for understanding eHealth results. The

framework has six dimensions in system, information and service quality, use

and satisfaction, and net benefits, but organizational and contextual factors

are considered out-of-scope. Since its debut in 2006, the BE Framework has been applied, adapted and cited by different jurisdictions,

organizations and groups in Canada and elsewhere as an overarching framework to

plan, conduct and report eHealth evaluation studies. Additional studies

continue to be published on a regular basis. Recognizing its limitations in

addressing contexts, there is a growing evidence base in the use of the BE Framework to evaluate the success of eHealth systems across different healthcare

settings.

References

Alsharif, S. (2012). Evaluation of medication turnaround time following implementation of scanning

digital prescriber order technology. MSc Internship Report in Health Informatics, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Bah, S., Alharthi, H., Mahalli, A. A. E., Jabali, A., Al-Qahtani M., & Al-Kahtani, N. (2011). Annual survey on the level and extent of usage of electronic

health records in government-related hospitals in eastern province, Saudi

Arabia. Perspectives in Health Information Management,8(Fall), 1b.

DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (1992). Information systems success: The quest for the dependent

variable. Information Systems Research, 3(1), 60–95.

DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (2003). The DeLone and McLean model of information systems

success: A ten-year update. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), 9–30.

Dow, R. (2012). The impact of end-user support on electronic medical record success in Ontario

primary care: A critical case study. MSc thesis in Information, University of Toronto.

Elliott, P. G. (2010). Evaluation of the implementation of an electronic occurrence reporting system at

Eastern Health, Newfoundland and Labrador (Phase One). PhD dissertation in Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s.

Forland, L. (2007). Evaluating the implementation of an electronic medical record for a health

organization-affiliated family practice clinic. MSc thesis in Health Informatics. University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada.

Ghaznavi, F. (2012). Design and evaluation of a multidisciplinary cancer conferencing platform. MSc thesis in Biomedical Engineering. Chalmers University of Technology and

University of Toronto.

Hagens, S., Zelmer, J., Frazer, C., Gheorghiu, B., & Leaver, C. (2015, February). Valuing national effects of digital health

investments: An applied method. Paper presented at Driving quality in informatics: Fulfilling the promise, an international conference addressing information technology and

communication in health, Victoria, BC, Canada.

Infoway. (2005). Canada Health Infoway Inc. corporate business plan 2005–06. Toronto: Author.

Infoway. (2006). Benefits evaluation survey process — System & use assessment survey. Canada Health Infoway benefits evaluation indicators technical report. Version

1.0, September 2006. Toronto: Author. Retrieved from https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/en/component/edocman/resources/toolkits/change-management/national-framework/monitoring-and-evaluation/resources-and-tools/991-benefits-evaluation-survey-process-system-use-assessment-survey

Infoway. (2012). Benefits evaluation survey process — System & use assessment survey. Canada Health Infoway benefits evaluation indicators technical report. Version

2.0, April 2012. Toronto: Author.

Kuhn, K., & Lau, F. (2014). Evaluation of a shared electronic health record. Healthcare Quarterly, 17(1), 30–35.

Lau, F. (2006). Increasing the rigor of health information system studies

through systematic reviews? In R. Abidi, P. Bath, & V. Keselj (Eds.), Proceedings of 11th International Symposium on Health Information Management

Research(iSHIMR). July 14 to 16, Halifax, NS, Canada.

Lau, F., Hagens, S., & Muttitt, S. (2007). A proposed benefits evaluation framework for health

information systems in Canada. Healthcare Quarterly, 10(1), 112–118.

Lau, F., Kuziemsky, C., Price, M., & Gardner, J. (2010). A review on systematic reviews of health information system

studies. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association, 17(6), 637–645. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2010.004838

Mensink, N., & Paterson, G. (2010). The evolution and uptake of a drug information system: The

case of a small Canadian province. In C. Safran, H. Marin, & S. Reti (Eds.), MEDINFO 2010 (pp. 352–355). Amsterdam: IOS Press. doi: 10.3233/978-1-60750-588-4-352.

Nagle, L. M., & Catford, P. (2008). Toward a model of successful electronic health record

adoption. Healthcare Quarterly, 11(3), 84–91.

Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information [NLCHI]. (2014). Nova Scotia post-implementation survey and interview results, March

2014. Retrieved from https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/en/component/edocman/resources/reports/benefits-evaluation/2099-atlantic-canada-iehr-labs-benefits-evaluation-project-phase-2-nova-scotia

Ng, Y. (2012). Key characteristics of health information exchange: A scoping review. MSc report in Health Informatics. University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada.

O’Grady, L., Witterman, H., Bender, J. L., Urowitz, S., Wiljer, D., & Jadad, A. R. (2009). Measuring the impact of a moving target: Towards a dynamic

framework for evaluating collaborative adaptive interactive technologies. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11(2), e20.

Paterson, G., Shaw, N., Grant, A., Leonard, K., Delisle, E., Mitchell, S., ...

Kraetschmer, N. (2010). A conceptual framework for analyzing how Canadian

physicians are using electronic medical records in clinical care. In C. Safran,

S. Reti, & H. F. Marin (Eds.), Proceedings of the 13th World Congress on Medical Informatics (pp. 141–145). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Shachak, A., Montgomery, C., Dow, R., Barnsley, J., Tu, K., Jadad, A. R., & Lemieux-Charles, L. (2013). End-user support for primary care electronic

medical records: a qualitative case study of users’ needs, expectations, and realities. Health Systems, 2(3), 198–212. doi: 10.1057/hs.2013.6

Steis, M. R., Prabhu, V. V., Kang, Y., Bowles, K. H., Fick, D., & Evans, L. (2012). Detection of delirium in community-dwelling persons with

dementia. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics,16(1). Retrieved from http://ojni.org/issues/?=1274

van der Meijden, M. J., Tange, H. J., Troost, J., & Hasman, A. (2003). Determinants of success of clinical information systems: A

literature review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 10(3), 235–243.

References Cited in Tables

Table 2.3

Ammenwerth, E., & de Keizer, N. (2004). An inventory of evaluation studies of information

technology in health care. Trends in evaluation research, 1982-2002. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 44(1), 44–56.

Balas, A. E., Boren, S. A., & Griffing, G. (1998). Computerized management of diabetes: a synthesis of

controlled trials. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 5(S), 295–299.

Balas, A. E., Austin, S. M., Mitchell, J. A., Ewigman, B. G., Bopp, K. D., & Brown, G. D. (1996). The clinical value of computerized information services. Archives of Family Medicine, 5(5), 271–278.

Cramer, K., Hartling, L., Wiebe, N., Russell, K., Crumley, E., Pusic, M., & Klassen, T. P. (2003). Computer-based delivery of health evidence: A systematic review of randomized

controlled trials and systematic reviews of the effectiveness of the process of

care and patient outcomes. Final report, part I. Edmonton, AB: Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

Delpierre, C., Cuzin, L., Fillaux, J., Alvarez, M., Massip, P., & Lang T. (2004). A systematic review of computer-based patient record systems

and quality of care: More randomized clinical trials or a broader approach? International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 15(5), 407–416.

Garg, A. X., Adhikari, N. K. J., McDonald, H., Rosas-Arellano, M. P., Devereaux,

P. J., Beyene, J., Sam, J., & Haynes, R. B. (2005). Effects of computer-based clinical decision support

systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293(10), 1223–1238.

Kaushal, R., Shojania, K. G., & Bates, D. W. (2003). Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical

decision support systems on medication safety. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(12), 1409–1416.

Kawamoto, K., Houlihan, C. A., Balas, E. A., & Lobach, D. F. (2005). Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support

systems: A systematic review of trials to identify features critical to

success. British Medical Journal, 330(7494), 765–768.

Mitchell, E., & Sullivan, F. A. (2001). A descriptive feast but an evaluative famine:

systematic review of published articles on primary care computing during

1980-97. British Medical Journal,322(7281), 279–282.

Montgomery, A. A., & Fahey, T. (1998). A systematic review of the use of computers in the management

of hypertension. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 52(8), 520–525.

Sullivan, F., & Mitchell, E. (1995). Has general practitioner computing made a difference to

patient care? British Medical Journal,311(7009), 848–852.

van der Loo, R. P., Gennip, E. M. S. J., Bakker, A. R., Hasman, A., & Rutten, F. F. H. (1995). Evaluation of automated information systems in

healthcare: An approach to classify evaluative studies. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 48(1/2), 45–52.

van der Meijden, M. J., Tange, H. J., Troost, J., & Hasman, A. (2003). Determinants of success of clinical information systems: A

literature review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 10(3), 235–243.

Walton, R., Dovey, S., Harvey, E., & Freemantle, N. (1999). Computer support for determining drug dose: systematic

review and meta analysis. British Medical Journal,318(7189), 984–990.

Table 2.5

British Columbia Ministry of Health [MOH]. (2011a). Evaluating the benefits: Telehealth — TeleOncology. Initial benefits evaluation assessment. Victoria, BC: Ministry of Health.

British Columbia Ministry of Health [MOH]. (2011b). Evaluating the benefits: Telehealth — teleOphthalmology. Inter Tribal Health Authority and the Ministry of Health Services. Victoria, BC: Ministry of Health.

British Columbia Ministry of Health [MOH]. (2013). Panorama vaccine inventory module. Benefits evaluation report. Victoria, BC: Ministry of Health.

Cousins, A., & Baldwin, A. (2014). eChart ambulatory project: EMR benefits measurement in a tertiary care facility. eHealth Conference, Vancouver, BC, June 3, 2014.

Deloitte. (2010). National impacts of generation 2 drug information systems. Technical Report, September 2010. Toronto: Canada Health Infoway. Retrieved

from https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/en/component/edocman/resources/reports/331-national-impact-of-generation-2-drug-information-systems-technical-report-full

Elliott, P., Martin, D., & Neville, D. (2014). Electronic clinical safety reporting system: A benefits

evaluation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2(1), e12.

Ernst & Young. (2014). Connecting patients with providers: A pan-Canadian study on remote patient

monitoring. Toronto: Canada Health Infoway. Retrieved from

https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/en/component/edocman/resources/reports/benefits-evaluation/1890-connecting-patients-with-providers-a-pan-canadian-study-on-remote-patient-monitoring-executive-summary

Gartner, Inc. (2013). British Columbia eHealth benefits estimates. Stamford, CT: Author.

Hagens, S., Kwan, D., Savage, C., & Nenadovic, M. (2009a). The impact of diagnostic imaging investments on the

Canadian healthcare system. Electronic Healthcare, 7(4), Online Exclusive.

Hagens, S., Kraetschmer, N., & Savage, C. (2009b). Findings from evaluations of the benefits of diagnostic

imaging systems. In J. G. McDaniel (Ed.), Advances in information technology and communication in health (pp. 136–141). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Lau, F., Lee, D., Quan, H., & Richards, C. (2010). An exploratory study to examine the use of SNOMED CT in a palliative care setting. Electronic Healthcare, 9(3), e12–e24.

Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information [NLCHI]. (2010). Evaluating the benefits — Newfoundland and Labrador provincial telehealth program: Chronic disease

management. St. John’s: Author.

Praxia Information Intelligence, & Gartner, Inc. (2010). Telehealth benefits and adoption: Connecting people and providers across Canada. Toronto and Stamford, CT: Authors.

PricewaterhouseCoopers [PWC]. (2013). The emerging benefits of electronic medical record use in community-based care. Toronto: Canada Health Infoway.

Table 2.6

Ahmadi, H., Rad, M. S., Nilashi, M., Ibrahim, O., & Almaee, A. (2013). Ranking the micro level critical factors of electronic

medical records adoption using toopsis method. Health Informatics — An International Journal (HIIJ), 2(4), 19–32.

Cusack, C. M., Hook, J. M., McGowan, J., Poon, E., & Atif, Z. (2010). Evaluation toolkit. Health information exchange projects, 2009 update (AHRQ Publication No. 10-0056-EF). Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Gu, Y., Warren, J., Day, K., Pollock, M., & White, S. (2012). Achieving acceptable structured eReferral forms. In K.

Butler-Henderson & K. Gray (Eds.), Proceedings of the 5th Australasian workshop on Health Informatics and Knowledge

Management(HIKM, 2012), Melbourne (pp. 31–40). Darlinghurst, Australia: Australian Computer Society.

Hotchkiss, D., Dianna, M., & Foreit, K. (2012). How can routine health information systems improve health systems functioning in

low-resource settings? Chapel Hill, NC: MEASURE Evaluation.

Nguyen, L., & Bakewell, L. (2011). Impact of nursing information systems on residential care

provision in an aged care provider. In ACIS 2011: Proceedings of the 22nd Australasian Conference on Information Systems :

Identifying the information systems discipline (pp. 1–10). Sydney: AIS eLibrary.

Warren, J., Pollock, M., Day, K., Gu, Y., & White, S. (2011). A framework for health IT evaluation. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health.

Warren, J., Gu, Y., Day, K., & Pollock, M. (2012). Approach to health innovation projects: Learnings from

eReferrals. Health Care and Informatics Review Online, 16(2), 17–23.

Table 2.7

British Columbia Ministry of Health [MOH]. (2011). Evaluating the benefits: Telehealth — teleOphthalmology. Inter Tribal Health Authority and the Ministry of Health Services. Victoria, BC: Ministry of Health.

British Columbia Ministry of Health [MOH]. (2013). Panorama vaccine inventory module (Benefits Evaluation Report). Victoria, BC: Ministry of Health.

Cousins, A., & Baldwin, A. (2014). eChart ambulatory project: EMR benefits measurement in a tertiary care facility. eHealth Conference, Vancouver, BC, June 3, 2014.

Eapen, B. R., & Chapman, B. (2015). Mobile access to ClinicalConnect: A user feedback survey on

usability, productivity, and quality. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 3(2), e35. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4011

Kuhn, K., & Lau, F. (2014). Evaluation of a shared electronic health record. Healthcare Quarterly, 17(1), 30–35.

Prince Edward Island [P.E.I.]. (2010). Prince Edward Island drug information system — Evaluation report. Charlottetown: Government of Prince Edward Island.

1 In 2014, the International Health Terminology Standards Development

Organisation (IHTSDO) responsible for SNOMED CT officially changed the name so SNOMED CT no longer refers to Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms, but

rather just SNOMED Clinical Terms. It has become a trade name rather than an acronym.

Annotate

EPUB