Skip to main content

Notes

table of contents

Chapter 23

Evaluation of Electronic Medical Records in Primary Care

A Case Study of Improving Primary Care through Health Information Technology

Lynne S. Nemeth, Francis Lau

23.1 Introduction

Translating research into practice continues to be a challenge within primary

care, evidenced by the inconsistent performance in delivery of recommended

healthcare (McGlynn et al., 2003). Organizational support for improvement and

implementation of guideline-based care in small primary care practices, where

the majority of healthcare is delivered, is often fragmented and underdeveloped

(Fisher, Berwick, & Davis, 2009).

Workflows in the primary care office are sometimes complicated and inefficient,

and replacing paper records with an EMR system does not fix these inefficiencies (Miller & Sim, 2004). To improve quality when implementing the EMR, workflow redesign is important (Fiscella & Geiger, 2006). Smaller primary care practices that operate outside of large

healthcare systems often lack systematic resources that assist them to set

priorities for quality improvement (QI), and develop the staff that provide and support clinical care. Time and

resources are needed to address the steep learning curve and the knowledge

development needs of the non-clinician staff. A flexible change management

strategy (Lorenzi, Kouroubali, Detmer, & Bloomrosen, 2009) and strategic planning is needed when adopting electronic

medical records that can be used beyond the ways of a paper medical record

system (Baron, 2007).

HIT adoption may be the catalyst to stimulate a process of change in the provision

of primary care service delivery that improves the practice as a system. When

all members of the primary care team have timely access to patient information,

the overall coordination of care can be improved, and team members can take on

new roles that enhance the quality of healthcare. Yet using EMRs, clinical decision support systems, order entry, appointment schedules, and

test results reporting systems requires the adoption and the creation of best

practices in implementation, use and maintenance of the systems. Transformation

of primary care is needed to redesign the system for improved care

coordination, quality and safety, which benefit from better use of HIT (Meyers & Clancy, 2009). A coherent model to assist practices with implementation of

evidence-based guidelines using HIT, grounded in the real-world experiences of small primary care offices, can

engage newer practices on the path to improve the quality and effectiveness of

the healthcare delivered.

23.2 Case Study: Improving Primary Care Through Health Information Technology

23.2.1 Aims

A series of seven studies that focused on Translation of Research into Practice

(TRIP) within the Practice Partner Research Network (PPRNet), a primary care practice-based research network in the United States, were

selected for secondary analysis to synthesize a decade of learning regarding

how to use health information technology (HIT) to improve quality in primary care practices. A comparative case analysis of

the findings of the seven studies created new insights regarding improving

quality using HIT. The specific aims of this project were:

- Complete a mixed methods secondary analysis to synthesize findings on using information technology (IT) to improve quality in primary care across seven nationally funded PPRNet initiatives.

- Examine current perspectives of PPRNet-TRIP participants on team development and on methods for developing and sustaining QI efforts.

- Integrate findings from PPRNet’s previous studies with the current perspectives of practice representatives to refine the overarching theory-based “PPRNet-TRIP QI Model”.

23.2.2 Background, Context, Settings, and Participants

PPRNet has conducted a consecutive series of research studies focused on TRIP funded by several United States agencies (Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality [AHRQ], National Cancer Institute [NCI], and National Institute for Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse [NIAAA]) since 2001. This national practice-based research network was established in

1995, at the Medical University of South Carolina. Up to 225 practices from 43

states in the U.S. participated in PPRNet activities through the quarterly extraction of electronic health record data

from their practices, for benchmarking and quality improvement, and

participation in PPRNet research trials and demonstration projects awarded during this time. Network

participants shared best practices in improving quality on selected areas of

interest at annual network meetings convened to form a collaborative learning

community hosted by PPRNet investigators. This particular study was implemented to reach across a body

of research that had focused on specific clinical areas for improvement, to

generate overarching lessons learned from a decade of specific research that

translated research into practice using electronic health records (EHRs).

23.2.3 Methods (Study Design, Data Sources/Collection)

Aim 1:

The mixed methods data from seven PPRNet studies were merged into an NVivo 9.0 database for qualitative secondary

analysis. The studies focused on the following indicators and were funded by

the following agencies.

- TRIP-II (cardiovascular disease and stroke secondary prevention) AHRQ

- A-TRIP (36 primary care indicators) AHRQ

- AA-TRIP (alcohol screening, brief intervention) NIAAA

- C-TRIP (colorectal cancer [CRC] screening) NCI

- MS-TRIP (medication safety) AHRQ

- SO-TRIP (screening, immunizations and diabetes care management) AHRQ

- AM-TRIP (alcohol screening, brief intervention, medication) NIAAA

Data were incorporated from the variety of sources from the participation of 134

practices (e-mail, meeting notes, site visit evaluations, focus groups,

interviews, observations, memos) for analyses within the NVivo 9.0 database. Additionally, the performance data on PPRNet measures were reviewed to identify practices that were effective in

implementing changes to improve performance in their practices on selected

measures. In the review of these various data, concepts related to how

practices revised clinical processes, procedures and roles were clarified and

compared across studies. Practice strategies for improvement within practices were examined after intense

immersion with the data, and a cross-case comparison method enabled discovery

of common features of each of the cases. Each of the studies listed above was

considered a case. An inductive and deductive process was used iteratively in

coding the data. The aim of these analyses were to draw out new ideas, to

expand on concepts previously noted in these studies, and also to fit data into

categories representing newer strategies that evolved over the decade. Current

literature representing the advances over the decade in HIT, quality and patient-centred care were used to search more deductively for

evidence of characteristics of these trends. An emphasis on data reduction was

needed to minimize redundancy/overlap in concepts and to improve the clarity of

a model for improvement that might be used to develop practices that are newer

in their adoption of HIT.

Aim 2:

The 2011 and 2012 PPRNet annual meetings provided opportunities to review the current perspectives of

PPRNet-TRIP participants. These diverse, national audiences of PPRNet practice members participated in the meetings held in Charleston, South

Carolina for networking and dissemination of best practices related to

Medication Safety, Standing Orders, Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention,

and Judicious Use of Antibiotics for Acute Respiratory Infections. Participants

represented rural, urban, community-based family and internal medicine

practices and included clinicians, clinical staff, practice managers, HIT support staff, and other office staff, primarily from small- to medium-sized

practices, but including a number of larger practices as well. Field notes were

taken regarding the Medication Safety component of the 2011 meeting that

reflected how practices that participated in the MS-TRIP 2 project made improvements in their practice, why working on medication safety

mattered to them, case examples of best practice strategies, and how these

improvements related to efforts towards Patient Centred Medical Home (PCMH), meaningful use, and other aspects of performance review. Practices shared

their best practice plans, and discussed timelines for implementing these

plans.

A theme of the 2011 annual meeting focused on using PPRNet reports and quality improvement approaches to achieve Patient Centred Medical

Home (PCMH) and other quality recognitions. One of the specific components of the 2011

meeting included a presentation of “Lessons Learned from 10 years of Translating Research into Practice” (Nemeth, 2011), and a panel of practice staff and providers from four practices

that had exemplified numerous strategies that were learned from Aim 1. The practice panel provided an opportunity to seek the perspectives of other

practices on how team development and sustaining quality improvement occurred

in practice. Field notes were collected at this meeting (the 2011 meeting

included 113 participants, with 57 practices represented) to document the

discussion. Topics included: practice progress towards improving quality

through participation in PPRNet; what has evolved and improved; how this was accomplished; and what is most

important to develop a team practice, to adopt and use HIT tools, to transform practice culture and quality, and to activate patients.

There was a deep review of concepts, discussion of strategies and many

questions and dialogue from the meeting participants, including discussion of

potentially missing components from the model.

An interview guide was pretested with four practices, and these four practices

presented their views on practice development and sustainability for QI at a panel presentation. Telephone interviews followed up the annual 2011

meeting to gain perspectives of other providers and staff that had participated

in PPRNet research. Interviews were conducted between 2011 and 2012, in the context of

current research underway within each practice, or practice initiatives to

improve and capture additional practice revenue from payer initiatives, such as

Patient Centred Medical Home pilots or Meaningful Use. The practice activities

underway during the years 2010 through 2012 incorporated new interests in

incentives with healthcare reform legislation passed.

The 2012 annual meeting included 98 practice participants, from 46 practices. In

a session related to promoting the judicious prescribing of antibiotics for

acute respiratory infections, we gathered practice perspectives in field notes

related to the use of a template for clinical decision support, how to embed

patient education into a structured visit guided by a template, and how to

respond to patients requesting antibiotics when they were not indicated.

Regarding the AM-TRIP project, we collected practice comments regarding the use of alcohol screening

and brief interventions, and medication management for high-risk drinkers. The

discussion reflected challenges with patients, reluctance from providers and

nursing staff and how these were overcome in practices that participated in

this study. Practice participants who did not participate in this study had the

opportunity to learn from these practices, and raise awareness of the progress

of other participating practices in improving performance on alcohol screening,

intervention and treatment. Field notes taken during these sessions documented

additional perspectives to the qualitative data that underlies the refined

model.

Aim 3:

This aim involved a creative synthesis in mapping the key concepts as variables

that impact the process of improving primary care. Once the four key concepts

were identified, the inputs and outputs related to these activities were mapped

as a visual logic model. Yet, the visual representation of the relationships

between these concepts evokes an understanding that makes practical sense to

many practicing clinicians and their staff who provide primary care. After

developing the visual figure the concepts and model were reviewed and, after an

iterative process of revision and presentation to numerous audiences, the new PPRNet model was finalized. A logic model was added to more clearly specify how the

model can be used as an implementation and evaluation framework similar to

other implementation science efforts.

23.2.4 Results (Principal Findings, Outcomes, Discussion, Conclusions,

Significance, Implications)

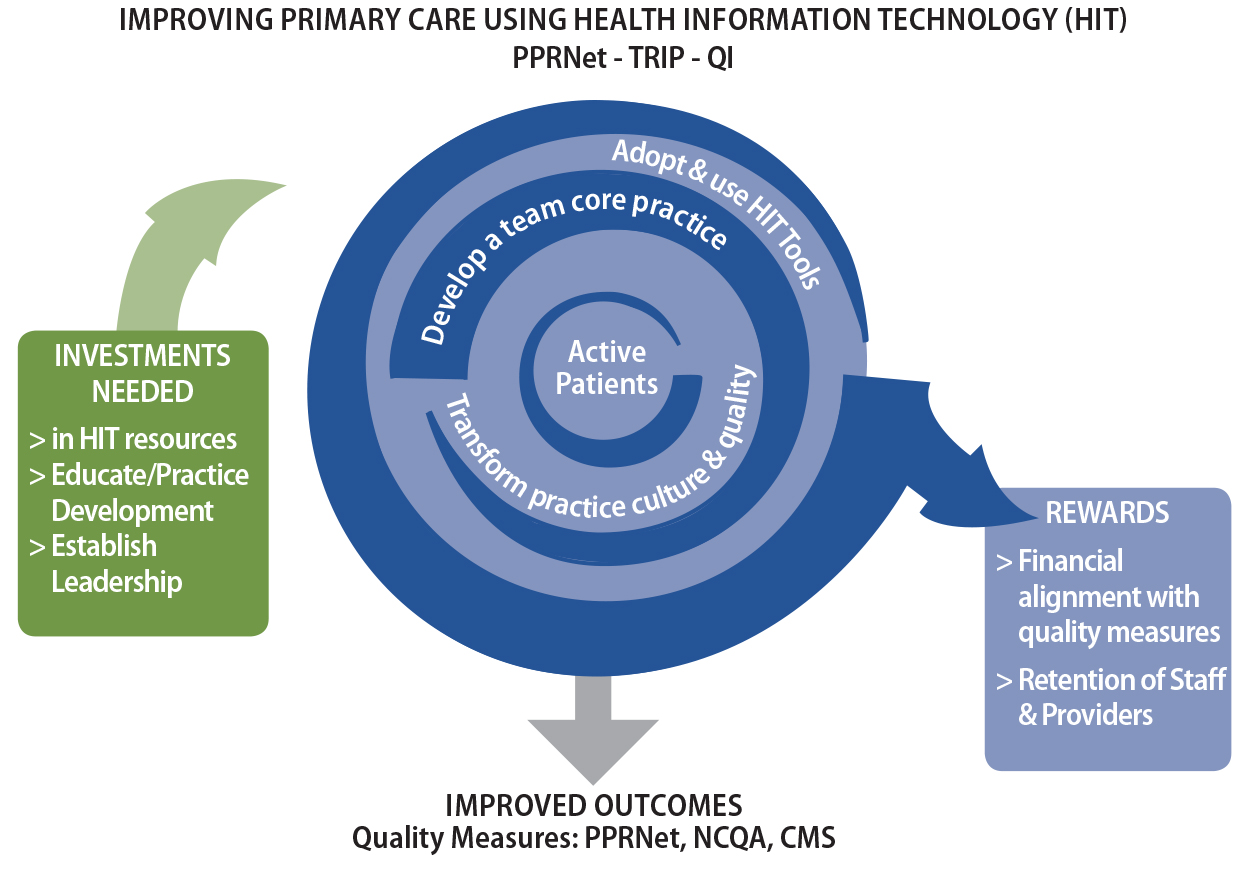

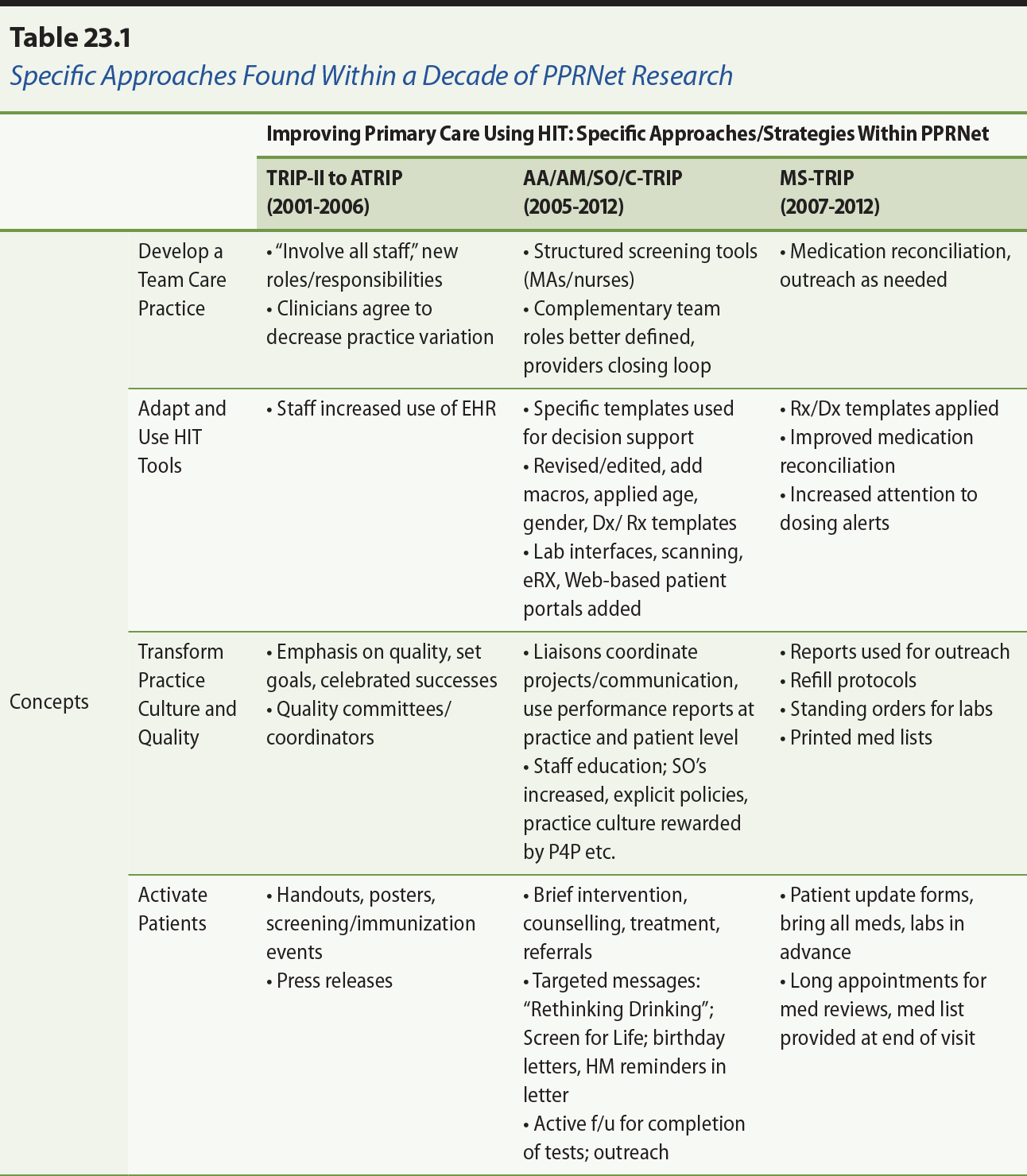

Aim 1. Secondary analysis of seven studies. The original PPRNet-TRIP QI model was developed through grounded theory development in the TRIP-II and A-TRIP studies which were formative to the subsequent PPRNet body of research. It became clear after lengthy immersion in the data,

reflecting on the evolution of practice activities over the decade, that

greater sophistication about how to improve on quality measures had occurred,

and that many practices were highly motivated to achieve a competitive

position. Four main concepts central to the new framework were identified:(a) developing a team care practice; (b) adapting and using HIT tools; (c) transforming the practice culture and quality; and (d) activating

patients.The four concepts emphasize the complex interactions and roles within primary

care practice, and interventions related to improvement on performance

measures. Figure 23.1 presents the framework, and Figure 23.1 elaborates how

the concepts in the early studies led to more sophisticated and complex

practice transformation.

Aim 2: Examine current perspectives of PPRNet-TRIP practice participants on team development and on methods for sustaining QI efforts. Twenty interviews were conducted with primary care providers of practices in PPRNet after the development of the revised model. The findings of these interviews

contributed to furthering an understanding of how practices developed their

teams, and what enabled them to sustain their efforts to improve. These

interviews elaborated provider perspectives about how they have developed

during a more recent trend towards rewards for quality and performance in

ambulatory care, a desire for designation as patient-centred medical homes, and

participation in early pilots from commercial payers, Medicare and Medicaid

demonstration projects, and meaningful use.

The key perspectives included support for developing enhanced roles for staff in

the practice to collect more data from patients, acting on decision support,

reminders, and alerts provided within the EHR, and implementing routine actions that save the provider time during clinical

encounters. The need for technical support to ensure that the EHR was set up correctly to provide the needed health information to be alerted was

clearly articulated, and often the role of technical support was provided by a

lead physician who was more technically savvy than others or more inclined to

take on this responsibility. In practices that lacked this internal leadership,

and in larger practices, IT support staff were needed and worked with a lead provider. Care coordination

and outreach to follow up on patients not at goals for values of quality

measures, or for those that needed chronic care management, was clearly

becoming a more important activity in practices that wanted to act on the

performance data that was generated within PPRNet reports. The activities related to increasing patient-centredness and patient

activation were newer activities in many of the practices, and the EHR resources proved to be a very important component of reaching out to patients

using Web portals, letters, and after-visit summaries and reminders to patients

to follow up on issues that were important to their care. Most of these

additional activities were undertaken to reap financial rewards for the quality

of care that the practice was aiming for.

The interviews established validity for the revisions to the PPRNet-Translating Research into Practice (TRIP) QI model that had been used within practices to improve quality of care using HIT.

Figure 23.1. PPRNet-TRIP QI: A refined framework guiding primary care improvement.

Note.From “Lessons learned from 10 years of translating research into practice,” by L. Nemeth, 2011, a presentation to the 16th annual meeting of the Practice

Partner Research Network (PPRNet), Medical University of South Carolina,

Charleston, SC. [Acknowledgement: AHRQ R03HS018830].

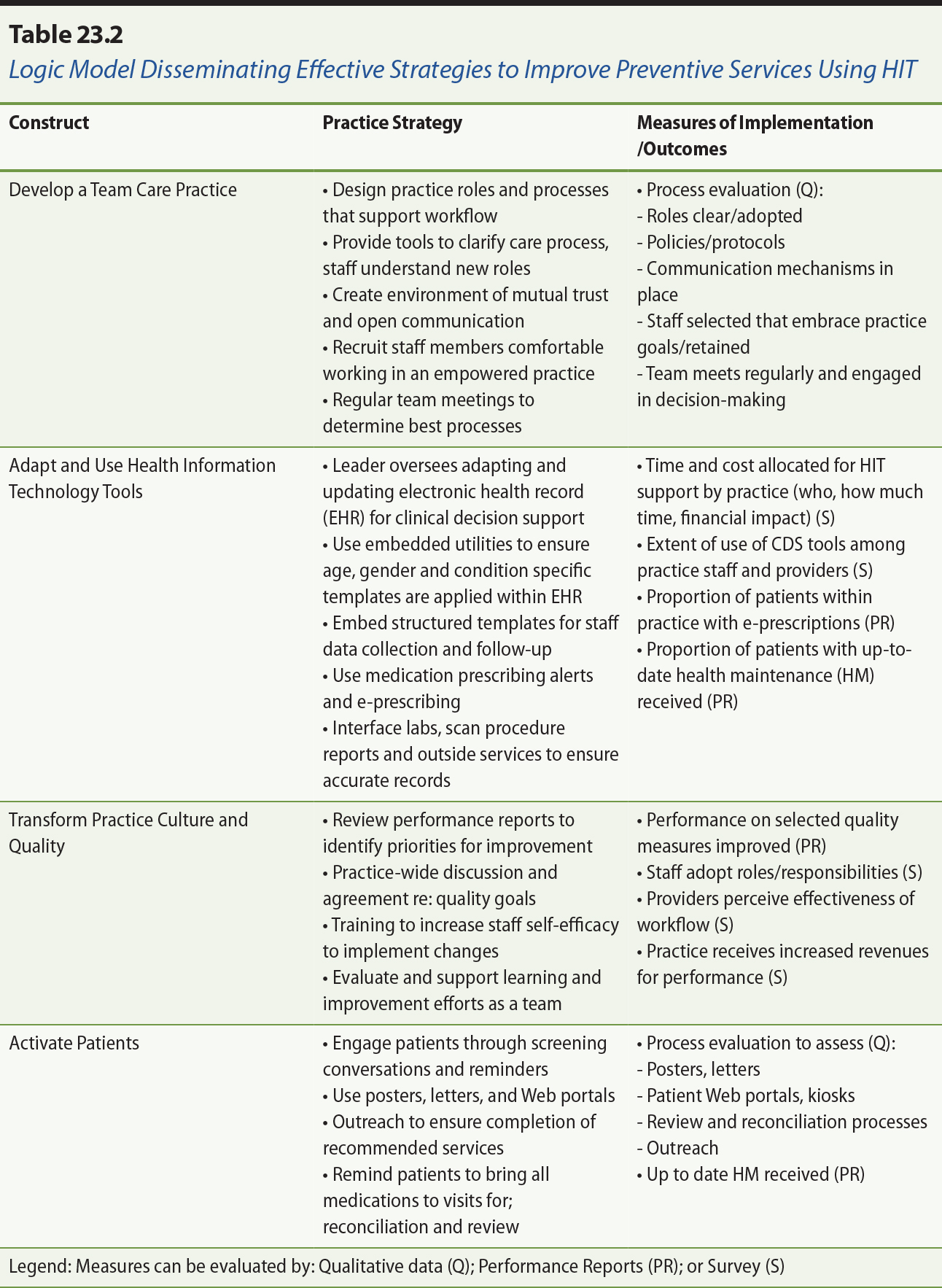

Aim 3: Integrate findings from PPRNet’s previous studies with the current perspectives of practice representatives to

refine the overarching theory-based “PPRNet-TRIP QI Model”. The four concepts in the new model — “Improving Primary Care through Health Information Technology” (IPC-HIT) — provide clear areas of focus for developing primary care practices towards high

performance on quality measures using HIT. Figure 23.1 presents the concepts and relationships of the framework. The

inputs to the process viewed as a logic model include that practices must

decide to make investments in HIT resources, which require the financial capacity and time to be allocated for

selection and learning to use the EHR. Education of the providers and staff is required, and leaders must be

appointed to ensure appropriate use of new systems. In some practices this

required hiring HIT coordinators, and in others a technically savvy clinician might take the lead.

Outputs of the process shown in the centre of the model in the figure include:

(a) financial rewards to the practice for their accomplishments in improvement,

and (b) retention of staff and providers who work together to increase value in

the healthcare services provided. Outcomes are demonstrated performance

improvements on measures that are important to the practice, such as PPRNet quality measures, and how they stand on these measures compared to the other

practices in PPRNet as noted by PPRNet medians and benchmarks (90th percentile).

Primary care practices that have used EHRs, participated in PPRNet practice-based research to improve the translation of research into practice,

or have been willing to share their strategies, successes, barriers, and

rewards have been able to make improvements towards higher performance. This

learning community has provided opportunities for reciprocal knowledge

dissemination from researchers to clinicians and vice versa. The lessons of

this decade of research together provide a model for other practices newer in

the transition and adoption of EHR tools to improve quality using their enhanced teams and a quality culture to

activate patients.

To explain these concepts in more detail, Table 23.1 presents “what” (concepts) and explains “how” (strategies) improvements in primary care have been made during participation

in PPRNet studies.

The logic model for IPC-HIT is presented in Table 23.2. For practices that are implementing the IPC-HIT model the following strategies and measures should be considered.

Note. From “Making sense of electronic medical record adoption as complex interventions in

primary health care,” by F. Lau, L. Nemeth, and J. Kim, 2012, a presentation to the Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research (CAHSPR) conference, Montreal. [Acknowledgement: AHRQ R03HS018830].

Acknowledgement: AHRQ R03HS018830 (Final progress report to AHRQ, 2013,

unpublished)

23.2.5 Issues, Guidance and Implications

Developing a Team Care Practice adds an understanding that providers engage their staff as partners to achieve

quality outcomes with patients. Front office staff members who receive and

schedule patients for follow-up care need to fully understand the goals for

improvement that the practice has set, to increase the follow through by

patients. Clinical staff participated to a larger extent in role expansion when

they were clear about the goals, what the practice wanted to do as a team, and

knew what their role expectations were.

Adapting and Using Health Information Tools involves developing more sophisticated use of the HIT tools available in the practice’s EHR. Effective use of EHR features requires practice customization related to patient populations served,

and practice patterns. Some degree of HIT expertise is needed to be able to customize these tools to provide efficient and

accurate data that drives reminders, alerts and any other decision support that

is needed to deliver quality primary care. This may require the allocation of

practice-based resources to ensure this component is managed effectively.

Transformation of Practice Culture and Quality is a process that evolves from engagement as a team, and using data from

performance to inspire practices to develop new approaches. This occurs while

learning, evaluating and reflecting on practice-specific progress in the

improvement efforts that have been prioritized, and the research evidence that

has been translated into practice.

Lastly, Activate Patients is the focus of practice-based efforts to improve. This often was seen as a

paradigm shift from an era of provider-dominated healthcare agendas to a focus

on developing patient-centredness in an era of stakeholder-engaged teams

seeking to improve knowledge regarding healthcare decisions and behaviours,

activation of patients as partners in their care, and understanding of values

and preferences of patients. In this study we learned that by using HIT tools, practice teams can reach out to patients to provide and validate recorded

health information data, present needed services, request patient decisions and

ensure medications are reconciled, and monitor chronic conditions as needed.

Noted within this synthesis of seven studies were both barriers and facilitators

to improvement in primary care using HIT.

- Barriers included: lack of practice leadership, vision and goals related to improvement using HIT; lack of provider agreement and consensus on approaches; need for HIT technical support, expertise and resources for using HIT effectively; staff and provider turnover, organizational change or change in practice ownership.

- Facilitators included: having practice policies and protocols; staff education and follow-up by leaders and clinicians; enhanced communication processes; streamlined tools and templates to improve workflow and efficiency; having a practice-wide approach that reinforced consistent staff expectations for adoption of expanded roles; and having providers close the loop on what practice staff initiate.

New questions and hypotheses were generated by this research. Most importantly,

the introduction of the four concepts in the IPC-HIT model provide direction to practices that want to improve their workflow and

processes to achieve goals of improved healthcare delivery to their activated

patients. By introducing the concepts and example practice strategies for

improving primary care through HIT, there should be corresponding implementation plans and measurement of outcomes

such as noted in the logic model in Table 23.2. Some examples of the hypotheses

related to processes and outcomes found in this table include:

- Staff will adopt expanded roles with clear policies and protocols regarding using the HIT in their work with patients.

- Providers will close the loop with patient care when staff members initiate patient services that are warranted by practice protocol.

- HIT will be supported by a designated leader within the practice, who will educate staff and providers regarding changes.

- Performance on clinical quality measures show improvement after developing practice teams with this model.

- Financial revenues are increased related to performance on clinical quality measures.

- Providers and staff are retained in practices that provide attention to the four concepts in the model.

A primary limitation to this research should be noted. The principal

investigator was the qualitative analyst of the original research and this

synthesis. Limited resources to review the wealth of qualitative data obtained

in the primary studies precluded analytic support. However, with the assistance

of the primary researchers, and review by the member practices in PPRNet, it was clear that the model was supported as valid. Overcoming this

limitation, it should be noted that the strength of the research was that it

was conducted in a national network and not limited to a specific geographic

region. Participants in PPRNet were clear about how they develop their staff toward high performance, and have

a track record evidenced in their performance data that demonstrated the

effective approaches resulted in clear improvements.

23.3 Summary

Over the past decade, PPRNet established a theoretically-informed framework for translating research into

practice (TRIP) in small- to medium-sized primary care practices that use the Practice Partner® electronic medical record (EMR). The PPRNet-TRIP Quality Improvement (QI) Model included three components: an intervention model, an improvement model,

and a practice development model that assists practices with implementation of

strategies to improve on selected performance measures. During the course of

the present research, we have streamlined the most important components to four

main concepts that can provide an organizing framework for improvement.

This research included a robust evaluation of the mixed methods data and lessons

learned from a decade of PPRNet-TRIP. The experience of PPRNet research participants and researchers enhanced understanding of the PPRNet-TRIP components and how practices improve primary care quality with their health

information technology and team-based approaches to care. The cross-case

analyses conducted through this research generated important themes, provided

new insights, and generated new hypotheses about factors that improve the

quality of care through the use of EMRs. The new framework will provide practical guidance for practices that are

undertaking these efforts to achieve meaningful use, patient centred medical

home recognition and paths for improved financial resources pertaining to

quality improvement in primary care practice.

References

Baron, R. J. (2007). Quality improvement with an electronic health record:

Achievable, but not automatic. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147(8), 549–552.

Fiscella, K., & Geiger, H. J. (2006). Health information technology and quality improvement for

community health centers. Health Affairs,25(2), 405–412. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.405

Fisher, E. S., Berwick, D. M., & Davis, K. (2009). Achieving health care reform — How physicians can help. New England Journal of Medicine, 360(24), 2495–2497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0903923

Lau, F., Nemeth, L. S., & Kim, J. (2012, May 30). Making sense of electronic medical record adoption as complex interventions in

primary health care. Presentation to the Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research

(CAHSPR) Conference, Montreal.

Lorenzi, N., Kouroubali, A., Detmer, D., & Bloomrosen, M. (2009). How to successfully select and implement electronic

health records (EHR) in small ambulatory practice settings. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 9(1), 15.

McGlynn, E. A., Asch, S. M., Adams, J., Keesey, J., Hicks, J., DeCristofaro, A.,

& Kerr, E. A. (2003). The quality of health care delivered to adults in the

United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 348(26), 2635–2645.

Meyers, D. S., & Clancy, C. M. (2009). Primary care: Too important to fail. Annals of Internal Medicine, 150(4), 272–273.

Miller, R. H., & Sim, I. (2004). Physicians’ use of electronic medical records: barriers and solutions. Health Affairs, 23(2), 116–126.

Nemeth, L. S. (2011, August 21–23). Lessons learned from 10 years of translating research into practice. Presentation to the 16th annual meeting of the Practice Partner Research

Network (PPRNet), Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC.

Annotate

EPUB