Skip to main content

Notes

table of contents

Evaluation of Personal Health Services and Records

24.1 Introduction

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) has changed information management practices at points of care, but it is also

empowering patients and individuals to take a more active role in their health

and care. Through consumer-focused health ICT, such as personal health records and personal health services (e.g., health

apps), people have the ability to be more engaged in their health. This is a

rapidly expanding market, yet the body of evidence showing the benefits of

these tools is smaller than it should be given the size of the market. Before

we describe some of the evidence, we should define some of the types of

consumer-focused health ICT.

There are many different terms used to describe aspects of consumer health ICT with, of course, sometimes overlapping and confusing definitions. For this

chapter, we will define and use the following:

- Personal Health Service(s)

- Personal Health Record

- Personal Health Information

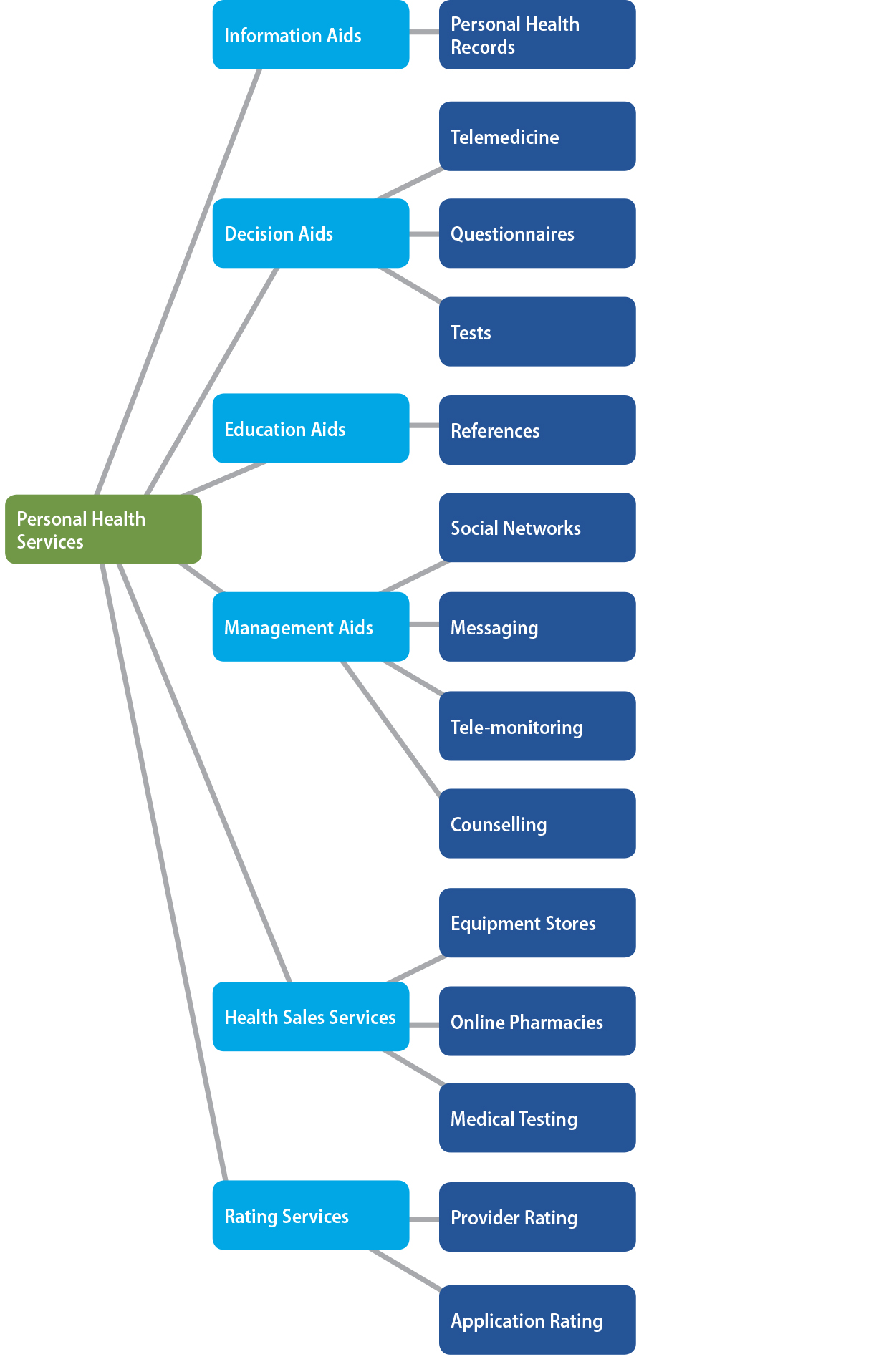

Personal Health Services (PHS) are more broadly defined than PHRs. These are any consumer-focused health ICT tools that can help people to engage in their own care. We have included PHRs in the broader taxonomy of PHS (see Figure 24.1). PHS do not necessarily have the mandate to provide a longitudinal record and can be

focused on a specific aspect of healthcare or wellness. For example, they could

provide information about foods or they could be a diet mobile health app that

lets you track your diet. A PHS could support home telemedicine or it could be an activity tracker. More

streamlined services have the advantage of focusing on a particular health

behaviour (e.g., quitting smoking, screening for a diagnosis, or improving

health literacy about a condition) and may be used in a targeted way to support

a specific health issue, assess for current risk, or help a person with a

behaviour change.

A Personal Health Record (PHR), also sometimes referred to as Personal Controlled Health Record (PCHR), is an ICT application designed to allow patients (or their designated caregivers) to

store and manage their personal health information (PHI). The American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) defines the PHR as an:

electronic, universally available, lifelong resource of health information

needed by individuals to make health decisions. Individuals own and manage the

information in the PHR, which comes from healthcare providers and the individual. The PHR is maintained in a secure and private environment, with the individual

determining rights of access. The PHR is medical and health information that is directed and maintained by the

patient and is separate from and does not replace the legal record of any

provider. (AHIMA, 2005)

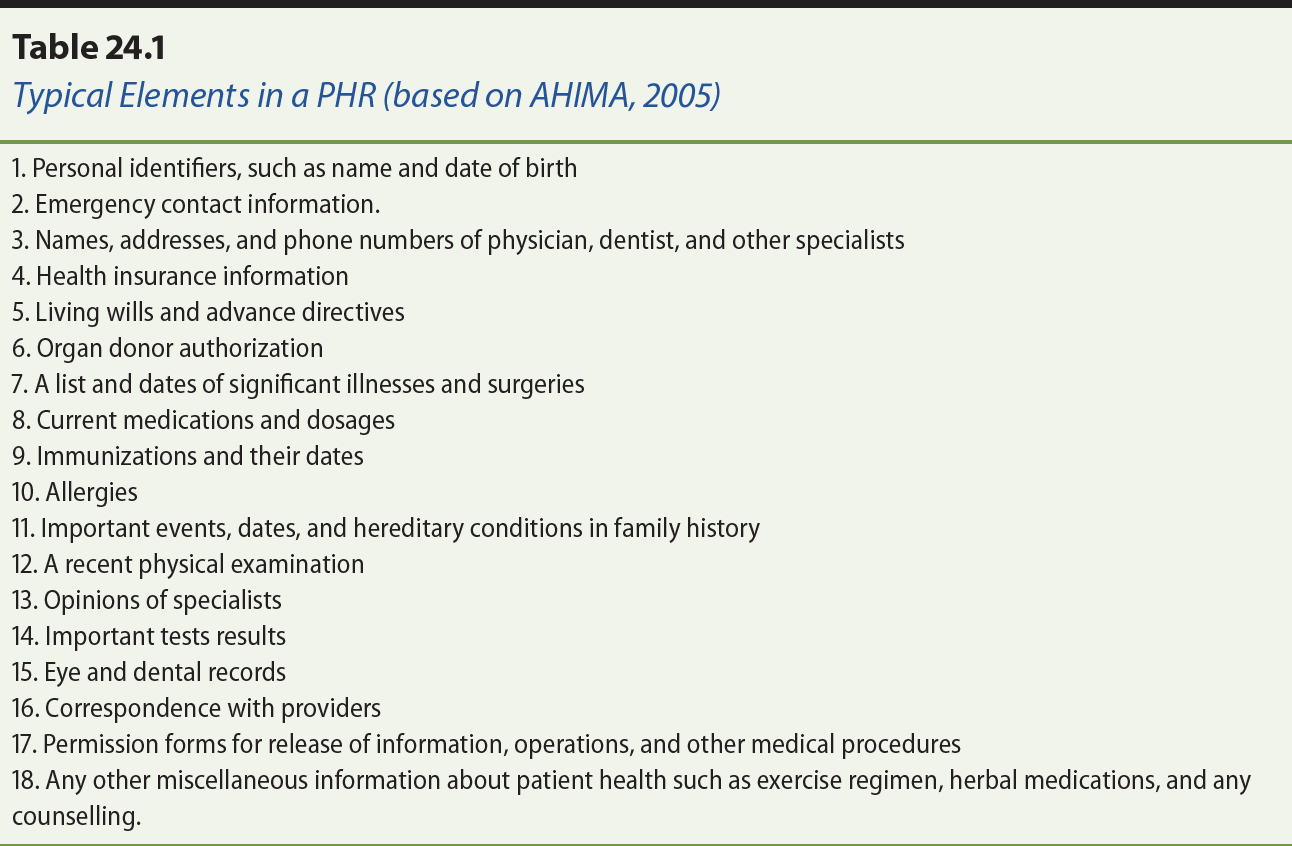

The specific data elements stored within a PHR varies between different application providers. Table 24.1 has some examples.

Some PHR systems are highly comprehensive, storing a wide amount of information about

patients. In other cases, the PHR application may deliberately be narrow in scope in an effort to maintain a

separation between consumer information and that in the custody and control of

a healthcare provider, but still maintain the concept of a longitudinal record.

PHRs that are tightly connected to a provider-based Electronic Medical Record (EMR) and represent subsets of the data represented in the corresponding provider

record are called tethered PHRs. In contrast, untethered PHRs are stand-alone and may provide users with the functionality to export/import

their personal health data to/from selected provider-based EMR systems, based on defined interoperability interfaces.

Figure 24.1. A breakdown of the broad range of personal health services.

PHRs are a place to store and manage personal health information (defined below).

Thus they can be considered an information aid for patients: a place to review,

recall or share personal health information when needed to support care.

However, PHRs may also integrate patient-centric knowledge bases or decision-support that

extends beyond the basic function of storing information. Such advanced

functionality may help with wellness activities, the management of chronic

diseases or other targeted health problems, such as addictions, obesity, and

mental health. Some of these functions are also available in Personal Health

Services, so there is admittedly overlap between a focused PHR and robust Personal Health Services.

Personal Health Information(PHI), in contrast to both PHS and PHR, is not an application where the information resides, but is the information

about an individual. It is information about an individual and that individual’s health, and can include information on diagnoses, medications, encounters with

care, lab results, health activities, and functional status. Table 24.1

provides application functions and also types of PHI.

Personal health information can reside in a number of ICT systems from consumer-focused ICT to provider-focused ICT and from health ICT to non-health ICT systems, such as government systems or insurance systems.

Personal Health Services have many potential benefits to multiple stakeholders.

This assumes that the PHS is properly designed, implemented, promoted, adopted, and, more importantly,

that it offers services that the users need and find useful. Some of the

reported potential benefits include: improving patient engagement in and

accountability for their own care; enabling patients to better manage their

health information and the information of their family members; providing

essential information to patients and other healthcare providers in emergencies

or while travelling; improving communication between patient and provider; and

reducing administrative costs (Tang, Ash, Bates, Overhage, & Sands, 2006). More specifically, potential benefits can be grouped into three

broad categories: (a) benefits to the consumer (i.e., the intended user of the PHS — the patient); (b) benefits to the consumer’s circle of care (i.e., caregivers, healthcare providers); and (c) benefits to

the overall healthcare system.

One often-stated purpose of using a PHS, such as a PHR, is supporting the user to engage in their care through accessing credible

health information. This can include both personal health information (their

own PHI) and general health information related to their health, such as information on

medications, health conditions, or how to exercise. Consumers can use credible

and evidence-based information to become better informed about their health,

which allows them to improve their own illness and wellness management. Many

chronic conditions require a degree of self-management, such as lifestyle

changes, adherence to medications, self-monitoring (e.g., blood pressure, blood

sugars). PHS can enable users to better manage their own chronic conditions by providing

tools, reminders and feedback. The chronic care model (Bodenheimer, Wagner, & Grumbach, 2002) highlights the need for engaged patients, and PHS can be one way of both engaging and empowering patients in their chronic disease

management.

PHS can improve communication between users and healthcare providers, such as

enabling users to provide information on function between visits, ask more

informed questions, as well as manage prescriptions, refills, and appointments

(Tang et al., 2006). Further, when patients share their PHI with healthcare providers, the providers can gain valuable information on daily

function, adherence, behaviours and symptoms that might not be easily captured

during visits for care. This can help with decision-making, lead to improved

communication, and result in better overall understanding of the issues around

the progress of a disease or wellness management, both by the provider and by

the patient (Tang et al., 2006). Informal caregivers, too, can benefit from

access to a patient’s PHR as a tool for communicating across the team, and to better understand the needs

and treatments and rationale for treatments.

PHS can also provide another treatment option for providers to offer to patients.

As evidence develops, providers will be able to increasingly suggest PHS options to help people with a range of health conditions such as asthma,

diabetes, fertility, glaucoma, HIV, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension (Price et al., 2015) and, in all likelihood,

other conditions in the future.

Potential PHS benefits to the healthcare system include reduced healthcare costs due to the

potential improved management of various chronic conditions. This, however, is

very much dependent on the actual capabilities of the PHS and how well it is adopted by its users. In addition, PHS have the potential to improve management of overall wellness; they emphasize

prevention, which, in turn, may help reduce overall healthcare system costs in

time (Tang et al., 2006). Although there is a potential, this is far from

proven and there is much evaluation to do to better understand the impact of PHS. Also to be considered is the effort that consumers will put into managing

their PHI through these various services (Ancker et al., 2015). Despite the potential

benefits, the evidence for PHSs and PHRs is limited and there are challenges to adopting these tools.

Personal Health Services, especially digital PHS, are relatively new and rapidly evolving. We do not yet know all of the

positive impacts or the unintended consequences of these tools.

24.3.1 Accuracy & Safety

One challenge that has been considered is the fact that the accuracy of PHI recorded online by patients (and their informal caregivers) is dependent on the

way it is collected, not to mention other factors such as computer literacy and

age of the person recording the information (Kim & Kim, 2010). The provenance1 of the PHI entered into PHR applications is important for judging its accuracy. For example, PHI data such as prescriptions and diagnoses that are entered by patients based on

recalling their memories of prior visits with care providers may have lower

accuracy than data directly downloaded from provider-facing (clinical)

information systems or entered based on written reports. Conversely, data is

that is recorded by people prospectively about their behaviours (e.g., diet,

exercise, medication adherence) may be more accurate than what is recalled or

described in a physician visit. PHRs have been found effective in increasing the data quality of provider

medication lists (Wright et al., 2008). Provenance of PHI is increasingly important as PHS and other systems are interconnected. Unfortunately, provenance information is

rarely kept in PHS and PHRs, which may compromise the objective of ensuring accuracy of PHI.

While PHRs are not considered medical devices in the classical sense, their

implementation may introduce hazards that require careful consideration.

Patient safety with PHS is a voiced concern from a provider perspective, both in terms of considering

data of unclear accuracy and origin in clinical decision-making, as well as in

terms of the potential safety ramifications of allowing patients to access

clinical data that they may not properly understand (Wynia, Torres, & Lemieux, 2011).

Patient controlled PHRs have been a safety concern in cases where patients are free to withhold

certain information from providers and in emergency situations (Chen & Zhong, 2012) or when access or sharing is not clear. Conversely, patients may

assume, incorrectly, that data is immediately shared and a message or comment

that is urgent and written in a PHS or PHR is viewed by a healthcare provider, for example, when it might not be. The

reverse is also true, as it has been argued that intelligent “assistant” services based on PHRs can help improve the safety of certain consumers, for example by providing

self-management support to patients with heart failure (Ferguson et al., 2010).

PHS and PHRs can provide many potential benefits but may also create new barriers, in

particular for populations with low technological or health literacy. The

adoption of various PHSs may create a health “digital divide”. Evidence for the significant impact of technology literacy has been shown in

several studies (Hilton et al., 2012; Wagner et al., 2012). Age has been

validated as a predictor for technology literacy. In a randomized trial, Wagner

et al. (2012) found that likelihood of PHR use decreased with age. Technology literacy in elderly populations has shown to

be a significant barrier. Kim and colleagues have shown that low-income,

elderly populations have a significant disadvantage of accessing online PHR services (Kim et al., 2007, 2009). These results agree with studies by Lober et

al. (2006), who also researched the impact of cognitive impairment and

disability in elderly populations.

Consumers do not commonly understand the medical terminology used by providers

or in provider-centric records. Translating that terminology to plain language

that is accessible to consumers requires significant effort if done manually.

Automated solutions have been developed based on ontological engineering

methods (Bonacina, Marceglia, Bertoldi, & Pinciroli, 2010) and data extraction from social health networks (Doing-Harris & Zeng-Treitler, 2011). Aside from the terminology, there is the question of how

much support consumers need in documenting and interpreting important medical

information, in particular their online test results. One study of consumer

support needs indicated that educational and psychosocial support services were

less frequently used than technical support (Wiljer et al., 2010).

PHI may be highly sensitive and thus needs to be carefully protected. There is

significant interest in PHI from a variety of legitimate parties, including various sectors of industry

(e.g., pharmaceuticals and marketers), employers, insurers, but also for

fraudulent use (e.g., identity theft, credit crime). Besides patient privacy,

provider privacy must also be considered, as the PHR may open up information to consumers and other parties that has traditionally

been kept in private EHRs or EMRs, accessible only to physicians.

Privacy concerns are among the most important barriers perceived by both

patients (Chhanabhai & Holt, 2007; Hoerbst, Kohl, Knaup, & Ammenwerth, 2010; Wen, Kreps, Zhu, & Miller, 2010) and providers (Wynia et al., 2011). Although the PHI maintained in PHS is equally sensitive to that information maintained in provider-facing systems,

PHR systems are not generally subject to the same privacy regulations and legal

protections.

Granular privacy controls that let consumers choose what data to share with

which healthcare provider are easier to interpret by users. However, such an

ability to withhold PHI raises significant care and liability issues (Cushman, Froomkin, Cava, Abril, & Goodman, 2010). Social networking features, while popular, are also challenging

as consumers have difficulty correctly interpreting their privacy controls

(Hartzler et al., 2011).

Cohort effects may be observed based on particular groups of consumer

populations; younger consumers tend to be more willing to share their PHI (Cushman et al., 2010). Particularly vulnerable populations, such as consumers

with conditions that are associated with social stigma, may require dedicated

considerations, for example, people with mental health conditions (Ennis, Rose,

Callard, Denis, & Wykes, 2011) and people living with HIV/AIDS (Kahn et al., 2010). Research on the latter population has indicated a high

willingness to share PHI with providers and a lower willingness to share with other non-professionals

(Teixeira, Gordon, Camhi, & Bakken, 2011).

Because of the patient-centric nature of PHSs and PHRs, traditional privacy consent directives such as identity-based access (“share PHI only with my doctor, Dr. X”) and role-based access (“share my PHI with all doctors”) are limited and fall short. The first alternative is considered too

restrictive to support a continuum of collaborative care around the patient

where the patient may have wished a new emergency room physician to have access

to PHI in an emergency. The second alternative is considered too broad (i.e.,

providing little protection). Specific process-based privacy models have been

developed in response to this problem (Mytilinaiou, Koufi, Malamateniou, & Vassilacopoulos, 2010). A related issue is emergency access to PHI in cases where the consumer is not able to provide consent (Chen & Zhong, 2012).

While, there have been several reviews completed examining the expected and

actual benefits of PHS, there is still a relative lack of evidence on the benefits of PHS. This is due, in part, to the rapidly changing nature of PHS and its various platforms. Smartphones and wearable technologies, for example,

are radically altering platforms where various PHS apps are being developed.

Genitsaridi, Kondylakis, Koumakis, Marias, and Tsiknakis (2015) reviewed and

evaluated 25 PHR systems based on four main requirements: free and open source software

requirement, Web-based system requirement, specific functionality requirements,

and architectural / technical requirements. Only four (MyOscar, Indivo-X,

Tolven, and OpenMRS) out of the 25 PHR systems reviewed met the free and open source software and Web-based

requirements, which were considered as basic requirements for a PHR system regardless of its functionality level. These four PHR systems, in addition to six other highly popular PHR systems, were then evaluated based on specific functionality requirements

(i.e., recording of a problem, diagnosis, and treatment, self-health

monitoring, communication management, security and access control, and

intelligence factors) as well as architectural requirements (i.e., stand-alone,

tethered, or interconnected). This study determined that there is a need for

better design of PHRs in order to improve self-management and integration into care processes

(Genitsaridi et al., 2015).

There is early evidence to support the use of PHRs in some chronic conditions. Based on a systematic review, there is evidence

that PHRs can be used to benefit the following: asthma, diabetes, fertility, glaucoma, HIV, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension (Price et al., 2015). There is a small body

of empirical evidence demonstrating benefit; however, many of these are

short-term studies looking only at changes in behaviour or early clinical

outcomes.

There are many factors that can impact the realization of benefits of PHS and PHR, beyond just the features and qualities (such as usability) of the tools

themselves. Thus, it is important to consider a wide range of factors in

evaluation including, among others: the PHS tool itself; the people who use it directly; the people who use it indirectly

(e.g., care providers who see summary information); the context of use; the

integration with care; the incentives (e.g., incentives from health insurance).

One key issue to consider when evaluating PHS is the interest and capacity of people to manage their health through

electronic means. As discussed previously, a health digital divide is possible

if services are available through PHS. Consider predictors of use of your users that include education, technical

knowledge, and health knowledge (Kim & Abner, 2016). Thus, evaluation (and implementation training) should carefully

consider the level of health and technological literacy of the users.

Kaiser Permanente, one of the largest health delivery organizations in the

United States, began implementing PHR solutions for their members in 2004. The PHR platform, My Health Manager, was tethered to their electronic health record (EHR) and included not only information services, but also provided means for secure

communication between patients and providers. The system was well received and

had been adopted by 2.4 million patients by 2008 (Silvestre, Sue, & Allen, 2009). By 2013, 65% of all eligible Kaiser Permanente members were

registered in My Health Manager. Early studies showed a significant decrease in office visits (26.2%) within a

period of three years, while at the same time there was a ninefold increase in

online consultations (phone visits) and a dramatic increase in

patient-generated secure messages (Chen, Garrido, Chock, Okawa, & Liang, 2009). Member satisfaction and health outcomes remained largely

unchanged over the three-year study, with a few exceptions, particularly with

respect to certain chronic disease conditions such as HbA1c control,

antidepressant medication management, and osteoporosis management in female

populations, which developed negatively. Further studies have also shown that

the PHR use has been correlated with significant health benefits in subpopulations such

as people with diverse languages and ethnicity (Garrido et al., 2015). However,

language and ethnicity both influenced the likelihood of members signing up to

the PHR system.

A recent study on Kaiser Permanente’s patient outcome improvements focused on virtual doctor-patient communication

(Reed, Graetz, Gordon, & Fung, 2015). My Health Manager provides the ability for patients and providers to communicate over e-mail as

well as schedule appointments and maintain many other health management aspects

online. Over 50% of study participants had used the e-mail feature at least

once, and almost 50% of participants prefer e-mail as the first method of

contact when it comes to their medical concerns. This resulted in 42% of

respondents reporting a reduction in phone contact and 36% of respondents

reporting a reduction in in-person visits. Overall, the use of the My Health Manager system resulted in 32% of users with chronic conditions improving their overall

health (Reed et al., 2015). In addition, the results of another study suggest

that using tools for health care management (i.e., online medication refills)

can result in improving medication adherence (Lyles et al., 2016).

Kaiser Permanente’s portal also provides users with access to information about prevention, health

promotion, and care gaps. In addition to improved communication and reduction

in office visits and phone calls, users of My Health Manager are more likely to participate in certain preventive measures, such as cancer

screening, hemoglobin A1c testing, and pneumonia vaccination (Henry, Shen,

Ahuja, Gould, & Kanter, 2016).

The National Health Service (NHS) in England attempted an implementation of a public nationwide PHR called HealthSpace in 2007. A three-year evaluation was completed by the Healthcare Innovation and

Policy Unit at the London School of Medicine and Dentistry (Greenhalgh, Hinder,

Stramer, Bratan, & Russell, 2010). It was initially inspired by the Kaiser Permanente model

outlined above. The NHS’ goals for this PHR were personalizing care, empowering patients, reducing NHS costs, and improving data quality and health literacy. HealthSpace included a basic account that would allow a person to record their own data

(e.g., blood pressures) and an advanced account where they could gain access to

their summary care record (a subset of PHI shared from the patient’s GP) and interact with their GP (to book appointments, message with questions). Additional features were planned

over time.

The evaluation of HealthSpace was a mixed method, multilevel case study. It covered the policy development,

implementation, and patient experience using both qualitative and quantitative

methods to develop a rich picture of HealthSpace.

The policy and project documentation that was evaluated in this case study

highlighted a focus on the technical and managerial aspects of implementing a PHR, with less focus on understanding the user requirements (e.g., through

observation and detailed analysis and testing). The evaluation highlighted a

design gap in user expectations and needs with respect to how the system was

implemented. The deployment of this particular PHR, unfortunately, resulted in poor initial uptake mostly due to a lack of

interest, perceived usefulness and ease of use, and a cumbersome account

creation process. During the PHR evaluation, HealthSpace users expressed disappointment in specific data being unavailable, the need for

data self-entry, and an inability to share their information with their

healthcare providers seamlessly. The study highlighted that HealthSpace was not aligned with the “attitudes, self-management practices, [and] identified information needs” of its potential users (Greenhalgh et al., 2010). The expected benefits of HealthSpace were not realized, in large part, due to this gap.

PHS and PHRs have the potential for wide ranging impact on care — both directly for the patient and indirectly for the care providers, care

organizations, and the overall healthcare system. Thus, we suggest considering

evaluation using a broad framework such as the Clinical Adoption Framework (see

chapter 3), which includes concepts from micro-level evaluation (system, use,

and patient level outcomes) to meso-level and macro-level influencing factors.

Also, we encourage the use of multiple methods when evaluating PHS, and a plan that incorporates various assessments to occur over time to see how

the PHSs are incorporated into health and wellness behaviours and into healthcare

systems. With multi-method studies, one can also develop feedback loops into

the PHS programs, using evaluation in an action research framework to improve the

chance of success and positive impact of using these tools. Large, single

trials, at this stage, may not be able to provide the richness of answers

needed to understand how PHSs are being used and why they are achieving (or not achieving) their outcomes.

Also, it is important to consider how to incorporate the rate of change of PHS features and functions into the evaluation, as these are rapidly evolving tools.

For example, evaluation can begin prior to system implementation by modelling

out the goals of the PHS implementation and related activities and mapping these into the meso- and

macro-level contexts. This may, for example, quickly highlight disconnects

between the goals of the PHS and macro-level aspects such as legislation or funding limitations for

providers (e.g., no mechanism for remuneration for e-communication). Usability

evaluations (both usability inspections with experts and usability testing with

potential users) can be completed with early prototypes. Once implemented,

pilot studies can explore user experience as well as the indirect experience of

providers when patients have access to PHS. Future studies can then begin to look at changes in behaviour and changes in

outcomes, both clinical and health system (e.g., numbers of visits, numbers of

e-visits, and capacity to see patients).

PHSs and PHRs are being increasingly implemented as part of health care systems. Despite the

efforts in implementation and adoption, the advertising of apps and wearables,

et cetera, there is still a gap in sufficient evaluation of PHS. We need a better understanding of how these tools are used and what the impact

these tools have on long-term outcomes, both health outcomes and such health

system outcomes as capacity and cost.

When planning an evaluation for PHS it is important to consider the goals and plan an evaluation based on those

goals and the potential direct and indirect impacts over time. Unintended

consequences should be considered. Depending on the scope of the PHS, the evaluation should be broad, assessing impact across the continuum of care

(i.e., across the patient’s circle of care). To do this, we advocate for multi-method studies that will

evaluate the design and adoption of the PHS tools early and throughout its life cycle. A deeper understanding of user needs

early (e.g., during concept design, the establishment of projects, the

development of policy) will better ensure that the final product meets the

actual needs of users. Finally, consider evaluation across the range of

dimensions in the Clinical Adoption Framework (see chapter 3) to provide a

breadth that is needed to understand the impact of PHS across the micro, meso and macro levels of the healthcare system.

American Health Information Management Association [AHIMA]. (2005). The role of the personal health record in the EHR. Journal of AHIMA, 76(7), 64A–64D.

Ancker, J. S., Witteman, H. O., Hafeez, B., Provencher, T., Van de Graaf, M., & Wei. E. (2015). The invisible work of personal health information management

among people with multiple chronic conditions: Qualitative interview study

among patients and providers. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(6), e137. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4381 PMID: 26043709 PMCID: 4526906

Bodenheimer, T., Wagner, E. H., & Grumbach, K. (2002). Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(14), 1775–1779.

Bonacina, S., Marceglia, S., Bertoldi, M., & Pinciroli, F. (2010). Modelling, designing, and implementing a family-based

health record prototype. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 40(6), 580–590. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2010.04.002

Chen, C., Garrido, T., Chock, D., Okawa, G., & Liang, L. (2009). The Kaiser Permanente electronic health record: Transforming

and streamlining modalities of care. Health Affairs, 28(2), 323–333. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.323

Chen, T., & Zhong, S. (2012). Emergency access authorization for personally controlled

online health care data. Journal of Medical Systems, 36(1), 291–300. doi: 10.1007/s10916-010-9475-2

Chhanabhai, P., & Holt, A. (2007). Consumers are ready to accept the transition to online and

electronic records if they can be assured of the security measures. Medscape General Medicine, 9(1), 8.

Cushman, R., Froomkin, A. M., Cava, A., Abril, P., & Goodman, K. W. (2010). Ethical, legal and social issues for personal health

records and applications. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 43(5), S51–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.05.003

Doing-Harris, K., & Zeng-Treitler, Q. (2011) Computer assisted update of consumer health vocabulary

through mining of social network data. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(2), e37. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1636

Ennis, L., Rose, D., Callard, F., Denis, M., & Wykes, T. (2011). Rapid progress or lengthy process? Electronic personal health

records in mental health. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 11(1), 117. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-117

Ferguson, G., Quinn, J., Horwitz, C., Swift, M., Allen, J., & Galescu, L. (2010). Towards a personal health management assistant. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 43(5 Suppl), S13–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.05.014

Garrido, T., Kanter, M., Meng, D., Turley, M., Wang, J., Sue, V., & Scott, L. (2015). Race/ethnicity, personal health record access, and quality of

care. American Journal of Managed Care, 21(2), e103–e113.

Genitsaridi, I., Kondylakis, H., Koumakis, L., Marias, K., & Tsiknakis, M. (2015). Evaluation of personal health record systems through the

lenses of EC research projects. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 59, 175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2013.11.004

Greenhalgh, T., Hinder, S., Stramer, K., Bratan, T., & Russell, J. (2010). Adoption, non-adoption, and abandonment of a personal

electronic health record: Case study of HealthSpace. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 341(7782), 1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5814

Hartzler, A., Skeels, M. M., Mukai, M., Powell, C., Klasnja, P., & Pratt, W. (2011, October). Sharing is caring, but not error free: transparency of granular controls for

sharing personal health information in social networks. Proceedings of the American Medical Informatics Association Annual Symposium,

Washington, DC (pp. 559–568). Retrieved from

http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3243199&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract

Henry, S. L., Shen, E., Ahuja, A., Gould, M. K., & Kanter, M. H. (2016). The online personal action plan. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(1), 71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.014

Hilton, J. F., Barkoff, L., Chang, O., Halperin, L., Ratanawongsa, N., Sarkar,

U., … Kahn, J. S. (2012). A cross-sectional study of barriers to personal health

record use among patients attending a safety-net clinic. PloS One, 7(2), e31888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031888

Hoerbst, A., Kohl, C. D., Knaup, P., & Ammenwerth, E. (2010). Attitudes and behaviors related to the introduction of

electronic health records among Austrian and German citizens. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 79(2), 81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.11.002

Kahn, J. S., Hilton, J. F., Van Nunnery, T., Leasure, S., Bryant, K. M., Hare,

C. B., & Thom, D. H. (2010). Personal health records in a public hospital: experience at

the HIV/AIDS clinic at San Francisco General Hospital. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 17(2), 224–228. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2009.000315

Kim, S., & Abner, E. (2016). Predictors affecting personal health information management

skills. Informatics for Health & Social Care, 41(3), 211.

Kim, E. -H., & Kim, Y. (2010). Digital divide: Use of electronic personal health record by different population

groups. Proceedings of the 32nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Buenos Aires (pp. 1759–1762). doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2010.5626732

Kim, E. -H., Stolyar, A., Lober, W. B., Herbaugh, A. L., Shinstrom, S. E.,

Zierler, B. K., … Kim, Y. (2007). Usage patterns of a personal health record by elderly and disabled users. American Medical Informatics Association Annual Symposium Proceedings, Chicago

(pp. 409–413). Retrieved from http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2655817&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract

Kim, E. –H., Stolyar, A., Lober, W. B., Herbaugh, A. L., Shinstrom, S. E., Zierler, B.

K., … Kim, Y. (2009). Challenges to using an electronic personal health record by a

low-income elderly population. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11(4), e44.

Lober, W. B., Zierler, B., Herbaugh, A., Shinstrom, S. E., Stolyar, A., Kim, E.

H., & Kim, Y. (2006). Barriers to the use of a personal health record by an elderly population.American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) Annual Symposium Proceedings, Washington, DC (pp. 514–518).

Lyles, C. R., Sarkar, U., Schillinger, D., Ralston, J. D., Allen, J. Y., Nguyen,

R., & Karter, A. J. (2016). Refilling medications through an online patient portal:

Consistent improvements in adherence across racial/ethnic groups. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association,23(e1), e28–e33. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv126

Mytilinaiou, E., Koufi, V., Malamateniou, F., & Vassilacopoulos, G. (2010). A context-aware approach to process-based PHR system security. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 156, 201–213.

Price, M., Bellwood, P., Kitson, N., Davies, I., Weber, J., & Lau, F. (2015). Conditions potentially sensitive to a personal health record (PHR) intervention, a systematic review. BioMed Central Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 15(1), 32. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0159-1

Reed, M., Graetz, I., Gordon, N., & Fung, V. (2015). Patient-initiated e-mails to providers: Associations with

out-of-pocket visit costs, and impact on care-seeking and health. The American Journal of Managed Care, 21(12), e632.

Silvestre, A., Sue, V. M., & Allen, J. Y. (2009). If you build it, will they come? The Kaiser Permanente

model of online health care. Health Affairs, 28(2), 334–344. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.334

Tang, P. C., Ash, J. S., Bates, D. W., Overhage, J. M., & Sands, D. Z. (2006). Personal health records: Definitions, benefits, and

strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 13(2), 121–126. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2025

Teixeira, P. A., Gordon, P., Camhi, E., & Bakken, S. (2011). HIV patients’ willingness to share personal health information electronically. Patient Education and Counseling, 84(2), e9–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.07.013

Wagner, P. J., Howard, S. M., Bentley, D. R., Seol, Y., & Sodomka, P. (2010). Incorporating patient perspectives into the personal health

record: Implications for care and caring. Perspectives in Health Information Management / AHIMA, American Health Information Management Association, 7, 1e.

Wagner, P. J., Dias, J., Howard, S., Kintziger, K. W., Hudson, M. F., Seol, Y., & Sodomka, P. (2012). Personal health records and hypertension control: A

randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 19(4), 626–634. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000349

Wen, K., Kreps, G., Zhu, F., & Miller, S. (2010). Consumers’ perceptions about and use of the internet for personal health records and

health information exchange: Analysis of the 2007 health information national

trends survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(4), e73. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1668

Wiljer, D., Leonard, K. J., Urowitz, S., Apatu, E., Massey, C., Quartey, N. K., & Catton, P. (2010). The anxious wait: Assessing the impact of patient accessible

EHRs for breast cancer patients. BioMed Central Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 10(1), 46–46.

doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-10-46

doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-10-46

Wright, A., Poon, E. G., Wald, J., Schnipper, J. L., Grant, R., Gandhi, T. K., … Middleton, B. (2008). Effectiveness of health maintenance reminders provided directly to patients. Proceedings of the American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) Annual Symposium, Washington, DC (p. 1183). Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18999087

Wynia, M. K., Torres, G. W., & Lemieux, J. (2011). Many physicians are willing to use patients’ electronic personal health records, but doctors differ by location, gender, and

practice. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 30(2), 266–273. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0342

1 Provenance is lineage of data, such as who entered the data, who may have

approved it, reviewed it, and modified it over time.

Annotate

EPUB