Skip to main content

Notes

table of contents

Chapter 9

Methods for Literature Reviews

Guy Paré, Spyros Kitsiou

9.1 Introduction

Literature reviews play a critical role in scholarship because science remains,

first and foremost, a cumulative endeavour (vom Brocke et al., 2009). As in any

academic discipline, rigorous knowledge syntheses are becoming indispensable in

keeping up with an exponentially growing eHealth literature, assisting

practitioners, academics, and graduate students in finding, evaluating, and

synthesizing the contents of many empirical and conceptual papers. Among other

methods, literature reviews are essential for: (a) identifying what has been

written on a subject or topic; (b) determining the extent to which a specific

research area reveals any interpretable trends or patterns; (c) aggregating

empirical findings related to a narrow research question to support

evidence-based practice; (d) generating new frameworks and theories; and (e)

identifying topics or questions requiring more investigation (Paré, Trudel, Jaana, & Kitsiou, 2015).

Literature reviews can take two major forms. The most prevalent one is the “literature review” or “background” section within a journal paper or a chapter in a graduate thesis. This section

synthesizes the extant literature and usually identifies the gaps in knowledge

that the empirical study addresses (Sylvester, Tate, & Johnstone, 2013). It may also provide a theoretical foundation for the proposed

study, substantiate the presence of the research problem, justify the research

as one that contributes something new to the cumulated knowledge, or validate

the methods and approaches for the proposed study (Hart, 1998; Levy & Ellis, 2006).

The second form of literature review, which is the focus of this chapter,

constitutes an original and valuable work of research in and of itself (Paré et al., 2015). Rather than providing a base for a researcher’s own work, it creates a solid starting point for all members of the community

interested in a particular area or topic (Mulrow, 1987). The so-called “review article” is a journal-length paper which has an overarching purpose to synthesize the

literature in a field, without collecting or analyzing any primary data (Green,

Johnson, & Adams, 2006).

When appropriately conducted, review articles represent powerful information

sources for practitioners looking for state-of-the art evidence to guide their

decision-making and work practices (Paré et al., 2015). Further, high-quality reviews become frequently cited pieces of

work which researchers seek out as a first clear outline of the literature when

undertaking empirical studies (Cooper, 1988; Rowe, 2014). Scholars who track

and gauge the impact of articles have found that review papers are cited and

downloaded more often than any other type of published article (Cronin, Ryan, & Coughlan, 2008; Montori, Wilczynski, Morgan, Haynes, & Hedges, 2003; Patsopoulos, Analatos, & Ioannidis, 2005). The reason for their popularity may be the fact that reading

the review enables one to have an overview, if not a detailed knowledge of the

area in question, as well as references to the most useful primary sources

(Cronin et al., 2008). Although they are not easy to conduct, the commitment to

complete a review article provides a tremendous service to one’s academic community (Paré et al., 2015; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006). Most, if not all, peer-reviewed journals in the fields of

medical informatics publish review articles of some type.

The main objectives of this chapter are fourfold: (a) to provide an overview of

the major steps and activities involved in conducting a stand-alone literature

review; (b) to describe and contrast the different types of review articles

that can contribute to the eHealth knowledge base; (c) to illustrate each

review type with one or two examples from the eHealth literature; and (d) to

provide a series of recommendations for prospective authors of review articles

in this domain.

9.2 Overview of the Literature Review Process and Steps

As explained in Templier and Paré (2015), there are six generic steps involved in conducting a review article:

- formulating the research question(s) and objective(s),

- searching the extant literature,

- screening for inclusion,

- assessing the quality of primary studies,

- extracting data, and

- analyzing data.

Although these steps are presented here in sequential order, one must keep in

mind that the review process can be iterative and that many activities can be

initiated during the planning stage and later refined during subsequent phases

(Finfgeld-Connett & Johnson, 2013; Kitchenham & Charters, 2007).

Formulating the research question(s) and objective(s): As a first step, members of the review team must appropriately justify the need

for the review itself (Petticrew & Roberts, 2006), identify the review’s main objective(s) (Okoli & Schabram, 2010), and define the concepts or variables at the heart of their

synthesis (Cooper & Hedges, 2009; Webster & Watson, 2002). Importantly, they also need to articulate the research

question(s) they propose to investigate (Kitchenham & Charters, 2007). In this regard, we concur with Jesson, Matheson, and Lacey

(2011) that clearly articulated research questions are key ingredients that

guide the entire review methodology; they underscore the type of information

that is needed, inform the search for and selection of relevant literature, and

guide or orient the subsequent analysis.

Searching the extant literature: The next step consists of searching the literature and making decisions about

the suitability of material to be considered in the review (Cooper, 1988).

There exist three main coverage strategies. First, exhaustive coverage means an

effort is made to be as comprehensive as possible in order to ensure that all

relevant studies, published and unpublished, are included in the review and,

thus, conclusions are based on this all-inclusive knowledge base. The second

type of coverage consists of presenting materials that are representative of

most other works in a given field or area. Often authors who adopt this

strategy will search for relevant articles in a small number of top-tier

journals in a field (Paré et al., 2015). In the third strategy, the review team concentrates on prior

works that have been central or pivotal to a particular topic. This may include

empirical studies or conceptual papers that initiated a line of investigation,

changed how problems or questions were framed, introduced new methods or

concepts, or engendered important debate (Cooper, 1988).

Screening for inclusion: The following step consists of evaluating the applicability of the material

identified in the preceding step (Levy & Ellis, 2006; vom Brocke et al., 2009). Once a group of potential studies has

been identified, members of the review team must screen them to determine their

relevance (Petticrew & Roberts, 2006). A set of predetermined rules provides a basis for including or

excluding certain studies. This exercise requires a significant investment on

the part of researchers, who must ensure enhanced objectivity and avoid biases

or mistakes. As discussed later in this chapter, for certain types of reviews

there must be at least two independent reviewers involved in the screening

process and a procedure to resolve disagreements must also be in place

(Liberati et al., 2009; Shea et al., 2009).

Assessing the quality of primary studies: In addition to screening material for inclusion, members of the review team may

need to assess the scientific quality of the selected studies, that is,

appraise the rigour of the research design and methods. Such formal assessment,

which is usually conducted independently by at least two coders, helps members

of the review team refine which studies to include in the final sample,

determine whether or not the differences in quality may affect their

conclusions, or guide how they analyze the data and interpret the findings

(Petticrew & Roberts, 2006). Ascribing quality scores to each primary study or considering

through domain-based evaluations which study components have or have not been

designed and executed appropriately makes it possible to reflect on the extent

to which the selected study addresses possible biases and maximizes validity

(Shea et al., 2009).

Extracting data: The following step involves gathering or extracting applicable information from

each primary study included in the sample and deciding what is relevant to the

problem of interest (Cooper & Hedges, 2009). Indeed, the type of data that should be recorded mainly depends

on the initial research questions (Okoli & Schabram, 2010). However, important information may also be gathered about how,

when, where and by whom the primary study was conducted, the research design

and methods, or qualitative/quantitative results (Cooper & Hedges, 2009).

Analyzing and synthesizing data: As a final step, members of the review team must collate, summarize,

aggregate, organize, and compare the evidence extracted from the included

studies. The extracted data must be presented in a meaningful way that suggests

a new contribution to the extant literature (Jesson et al., 2011). Webster and

Watson (2002) warn researchers that literature reviews should be much more than

lists of papers and should provide a coherent lens to make sense of extant

knowledge on a given topic. There exist several methods and techniques for

synthesizing quantitative (e.g., frequency analysis, meta-analysis) and

qualitative (e.g., grounded theory, narrative analysis, meta-ethnography)

evidence (Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young, & Sutton, 2005; Thomas & Harden, 2008).

9.3 Types of Review Articles and Brief Illustrations

EHealth researchers have at their disposal a number of approaches and methods

for making sense out of existing literature, all with the purpose of casting

current research findings into historical contexts or explaining contradictions

that might exist among a set of primary research studies conducted on a

particular topic. Our classification scheme is largely inspired from Paré and colleagues’ (2015) typology. Below we present and illustrate those review types that we

feel are central to the growth and development of the eHealth domain.

9.3.1 Narrative Reviews

The narrative review is the “traditional” way of reviewing the extant literature and is skewed towards a qualitative

interpretation of prior knowledge (Sylvester et al., 2013). Put simply, a

narrative review attempts to summarize or synthesize what has been written on a

particular topic but does not seek generalization or cumulative knowledge from

what is reviewed (Davies, 2000; Green et al., 2006). Instead, the review team

often undertakes the task of accumulating and synthesizing the literature to

demonstrate the value of a particular point of view (Baumeister & Leary, 1997). As such, reviewers may selectively ignore or limit the attention

paid to certain studies in order to make a point. In this rather unsystematic

approach, the selection of information from primary articles is subjective,

lacks explicit criteria for inclusion and can lead to biased interpretations or

inferences (Green et al., 2006). There are several narrative reviews in the

particular eHealth domain, as in all fields, which follow such an unstructured

approach (Silva et al., 2015; Paul et al., 2015).

Despite these criticisms, this type of review can be very useful in gathering

together a volume of literature in a specific subject area and synthesizing it.

As mentioned above, its primary purpose is to provide the reader with a

comprehensive background for understanding current knowledge and highlighting

the significance of new research (Cronin et al., 2008). Faculty like to use

narrative reviews in the classroom because they are often more up to date than

textbooks, provide a single source for students to reference, and expose

students to peer-reviewed literature (Green et al., 2006). For researchers,

narrative reviews can inspire research ideas by identifying gaps or

inconsistencies in a body of knowledge, thus helping researchers to determine

research questions or formulate hypotheses. Importantly, narrative reviews can

also be used as educational articles to bring practitioners up to date with

certain topics of issues (Green et al., 2006).

Recently, there have been several efforts to introduce more rigour in narrative

reviews that will elucidate common pitfalls and bring changes into their

publication standards. Information systems researchers, among others, have

contributed to advancing knowledge on how to structure a “traditional” review. For instance, Levy and Ellis (2006) proposed a generic framework for

conducting such reviews. Their model follows the systematic data processing

approach comprised of three steps, namely: (a) literature search and screening;

(b) data extraction and analysis; and (c) writing the literature review. They

provide detailed and very helpful instructions on how to conduct each step of

the review process. As another methodological contribution, vom Brocke et al.

(2009) offered a series of guidelines for conducting literature reviews, with a

particular focus on how to search and extract the relevant body of knowledge.

Last, Bandara, Miskon, and Fielt (2011) proposed a structured, predefined and

tool-supported method to identify primary studies within a feasible scope,

extract relevant content from identified articles, synthesize and analyze the

findings, and effectively write and present the results of the literature

review. We highly recommend that prospective authors of narrative reviews

consult these useful sources before embarking on their work.

Darlow and Wen (2015) provide a good example of a highly structured narrative

review in the eHealth field. These authors synthesized published articles that

describe the development process of mobile health (m-health) interventions for

patients’ cancer care self-management. As in most narrative reviews, the scope of the

research questions being investigated is broad: (a) how development of these

systems are carried out; (b) which methods are used to investigate these

systems; and (c) what conclusions can be drawn as a result of the development

of these systems. To provide clear answers to these questions, a literature

search was conducted on six electronic databases and Google Scholar. The search was performed using several terms and free text words, combining

them in an appropriate manner. Four inclusion and three exclusion criteria were

utilized during the screening process. Both authors independently reviewed each

of the identified articles to determine eligibility and extract study

information. A flow diagram shows the number of studies identified, screened,

and included or excluded at each stage of study selection. In terms of

contributions, this review provides a series of practical recommendations for

m-health intervention development.

9.3.2 Descriptive or Mapping Reviews

The primary goal of a descriptive review is to determine the extent to which a body of knowledge in a particular research

topic reveals any interpretable pattern or trend with respect to pre-existing

propositions, theories, methodologies or findings (King & He, 2005; Paré et al., 2015). In contrast with narrative reviews, descriptive reviews follow a

systematic and transparent procedure, including searching, screening and

classifying studies (Petersen, Vakkalanka, & Kuzniarz, 2015). Indeed, structured search methods are used to form a

representative sample of a larger group of published works (Paré et al., 2015). Further, authors of descriptive reviews extract from each study

certain characteristics of interest, such as publication year, research

methods, data collection techniques, and direction or strength of research

outcomes (e.g., positive, negative, or non-significant) in the form of

frequency analysis to produce quantitative results (Sylvester et al., 2013). In

essence, each study included in a descriptive review is treated as the unit of

analysis and the published literature as a whole provides a database from which

the authors attempt to identify any interpretable trends or draw overall

conclusions about the merits of existing conceptualizations, propositions,

methods or findings (Paré et al., 2015). In doing so, a descriptive review may claim that its findings

represent the state of the art in a particular domain (King & He, 2005).

In the fields of health sciences and medical informatics, reviews that focus on

examining the range, nature and evolution of a topic area are described by

Anderson, Allen, Peckham, and Goodwin (2008) as mapping reviews. Like descriptive reviews, the research questions are generic and usually

relate to publication patterns and trends. There is no preconceived plan to

systematically review all of the literature although this can be done. Instead,

researchers often present studies that are representative of most works

published in a particular area and they consider a specific time frame to be

mapped.

An example of this approach in the eHealth domain is offered by DeShazo,

Lavallie, and Wolf (2009). The purpose of this descriptive or mapping review

was to characterize publication trends in the medical informatics literature

over a 20-year period (1987 to 2006). To achieve this ambitious objective, the

authors performed a bibliometric analysis of medical informatics citations

indexed in MEDLINE using publication trends, journal frequencies, impact factors, Medical Subject

Headings (MeSH) term frequencies, and characteristics of citations. Findings

revealed that there were over 77,000 medical informatics articles published

during the covered period in numerous journals and that the average annual

growth rate was 12%. The MeSH term analysis also suggested a strong

interdisciplinary trend. Finally, average impact scores increased over time

with two notable growth periods. Overall, patterns in research outputs that

seem to characterize the historic trends and current components of the field of

medical informatics suggest it may be a maturing discipline (DeShazo et al.,

2009).

9.3.3 Scoping Reviews

Scoping reviews attempt to provide an initial indication of the potential size and nature of the

extant literature on an emergent topic (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Daudt, van Mossel, & Scott, 2013; Levac, Colquhoun, & O’Brien, 2010). A scoping review may be conducted to examine the extent, range and

nature of research activities in a particular area, determine the value of

undertaking a full systematic review (discussed next), or identify research

gaps in the extant literature (Paré et al., 2015). In line with their main objective, scoping reviews usually

conclude with the presentation of a detailed research agenda for future works

along with potential implications for both practice and research.

Unlike narrative and descriptive reviews, the whole point of scoping the field

is to be as comprehensive as possible, including grey literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Inclusion and exclusion criteria must be established to help

researchers eliminate studies that are not aligned with the research questions.

It is also recommended that at least two independent coders review abstracts

yielded from the search strategy and then the full articles for study selection

(Daudt et al., 2013). The synthesized evidence from content or thematic

analysis is relatively easy to present in tabular form (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Thomas & Harden, 2008).

One of the most highly cited scoping reviews in the eHealth domain was published

by Archer, Fevrier-Thomas, Lokker, McKibbon, and Straus (2011). These authors

reviewed the existing literature on personal health record (PHR) systems including design, functionality, implementation, applications,

outcomes, and benefits. Seven databases were searched from 1985 to March 2010.

Several search terms relating to PHRs were used during this process. Two authors independently screened titles and

abstracts to determine inclusion status. A second screen of full-text articles,

again by two independent members of the research team, ensured that the studies

described PHRs. All in all, 130 articles met the criteria and their data were extracted

manually into a database. The authors concluded that although there is a large

amount of survey, observational, cohort/panel, and anecdotal evidence of PHR benefits and satisfaction for patients, more research is needed to evaluate the

results of PHR implementations. Their in-depth analysis of the literature signalled that there

is little solid evidence from randomized controlled trials or other studies

through the use of PHRs. Hence, they suggested that more research is needed that addresses the current

lack of understanding of optimal functionality and usability of these systems,

and how they can play a beneficial role in supporting patient self-management

(Archer et al., 2011).

9.3.4 Forms of Aggregative Reviews

Healthcare providers, practitioners, and policy-makers are nowadays overwhelmed

with large volumes of information, including research-based evidence from

numerous clinical trials and evaluation studies, assessing the effectiveness of

health information technologies and interventions (Ammenwerth & de Keizer, 2004; Deshazo et al., 2009). It is unrealistic to expect that all

these disparate actors will have the time, skills, and necessary resources to

identify the available evidence in the area of their expertise and consider it

when making decisions. Systematic reviews that involve the rigorous application

of scientific strategies aimed at limiting subjectivity and bias (i.e.,

systematic and random errors) can respond to this challenge.

Systematic reviews attempt to aggregate, appraise, and synthesize in a single source all empirical

evidence that meet a set of previously specified eligibility criteria in order

to answer a clearly formulated and often narrow research question on a

particular topic of interest to support evidence-based practice (Liberati et

al., 2009). They adhere closely to explicit scientific principles (Liberati et

al., 2009) and rigorous methodological guidelines (Higgins & Green, 2008) aimed at reducing random and systematic errors that can lead to

deviations from the truth in results or inferences. The use of explicit methods

allows systematic reviews to aggregate a large body of research evidence,

assess whether effects or relationships are in the same direction and of the

same general magnitude, explain possible inconsistencies between study results,

and determine the strength of the overall evidence for every outcome of

interest based on the quality of included studies and the general consistency

among them (Cook, Mulrow, & Haynes, 1997). The main procedures of a systematic review involve:

- Formulating a review question and developing a search strategy based on explicit inclusion criteria for the identification of eligible studies (usually described in the context of a detailed review protocol).

- Searching for eligible studies using multiple databases and information sources, including grey literature sources, without any language restrictions.

- Selecting studies, extracting data, and assessing risk of bias in a duplicate manner using two independent reviewers to avoid random or systematic errors in the process.

- Analyzing data using quantitative or qualitative methods.

- Presenting results in summary of findings tables.

- Interpreting results and drawing conclusions.

Many systematic reviews, but not all, use statistical methods to combine the

results of independent studies into a single quantitative estimate or summary

effect size. Known as meta-analyses, these reviews use specific data extraction and statistical techniques (e.g.,

network, frequentist, or Bayesian meta-analyses) to calculate from each study

by outcome of interest an effect size along with a confidence interval that

reflects the degree of uncertainty behind the point estimate of effect

(Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009; Deeks, Higgins, & Altman, 2008). Subsequently, they use fixed or random-effects analysis models

to combine the results of the included studies, assess statistical

heterogeneity, and calculate a weighted average of the effect estimates from

the different studies, taking into account their sample sizes. The summary

effect size is a value that reflects the average magnitude of the intervention

effect for a particular outcome of interest or, more generally, the strength of

a relationship between two variables across all studies included in the

systematic review. By statistically combining data from multiple studies,

meta-analyses can create more precise and reliable estimates of intervention

effects than those derived from individual studies alone, when these are

examined independently as discrete sources of information.

The review by Gurol-Urganci, de Jongh, Vodopivec-Jamsek, Atun, and Car (2013) on

the effects of mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare

appointments is an illustrative example of a high-quality systematic review

with meta-analysis. Missed appointments are a major cause of inefficiency in

healthcare delivery with substantial monetary costs to health systems. These

authors sought to assess whether mobile phone-based appointment reminders

delivered through Short Message Service (SMS) or Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) are effective in improving rates of patient attendance and reducing overall

costs. To this end, they conducted a comprehensive search on multiple databases

using highly sensitive search strategies without language or publication-type

restrictions to identify all RCTs that are eligible for inclusion. In order to minimize the risk of omitting

eligible studies not captured by the original search, they supplemented all

electronic searches with manual screening of trial registers and references

contained in the included studies. Study selection, data extraction, and risk

of bias assessments were performed independently by two coders using standardized methods to ensure consistency and to

eliminate potential errors. Findings from eight RCTs involving 6,615 participants were pooled into meta-analyses to calculate the

magnitude of effects that mobile text message reminders have on the rate of

attendance at healthcare appointments compared to no reminders and phone call

reminders.

Meta-analyses are regarded as powerful tools for deriving meaningful

conclusions. However, there are situations in which it is neither reasonable

nor appropriate to pool studies together using meta-analytic methods simply

because there is extensive clinical heterogeneity between the included studies

or variation in measurement tools, comparisons, or outcomes of interest. In

these cases, systematic reviews can use qualitative synthesis methods such as

vote counting, content analysis, classification schemes and tabulations, as an

alternative approach to narratively synthesize the results of the independent

studies included in the review. This form of review is known as qualitative systematic review.

A rigorous example of one such review in the eHealth domain is presented by

Mickan, Atherton, Roberts, Heneghan, and Tilson (2014) on the use of handheld

computers by healthcare professionals and their impact on access to information

and clinical decision-making. In line with the methodological guidelines for systematic reviews, these authors: (a) developed and registered with PROSPERO (www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/) an a priori review protocol; (b) conducted comprehensive searches for

eligible studies using multiple databases and other supplementary strategies

(e.g., forward searches); and (c) subsequently carried out study selection,

data extraction, and risk of bias assessments in a duplicate manner to

eliminate potential errors in the review process. Heterogeneity between the

included studies in terms of reported outcomes and measures precluded the use

of meta-analytic methods. To this end, the authors resorted to using narrative

analysis and synthesis to describe the effectiveness of handheld computers on

accessing information for clinical knowledge, adherence to safety and clinical

quality guidelines, and diagnostic decision-making.

In recent years, the number of systematic reviews in the field of health

informatics has increased considerably. Systematic reviews with discordant

findings can cause great confusion and make it difficult for decision-makers to

interpret the review-level evidence (Moher, 2013). Therefore, there is a

growing need for appraisal and synthesis of prior systematic reviews to ensure

that decision-making is constantly informed by the best available accumulated

evidence. Umbrella reviews, also known as overviews of systematic reviews, are tertiary types of evidence

synthesis that aim to accomplish this; that is, they aim to compare and

contrast findings from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Becker & Oxman, 2008). Umbrella reviews generally adhere to the same principles and

rigorous methodological guidelines used in systematic reviews. However, the

unit of analysis in umbrella reviews is the systematic review rather than the

primary study (Becker & Oxman, 2008). Unlike systematic reviews that have a narrow focus of inquiry,

umbrella reviews focus on broader research topics for which there are several

potential interventions (Smith, Devane, Begley, & Clarke, 2011). A recent umbrella review on the effects of home telemonitoring

interventions for patients with heart failure critically appraised, compared,

and synthesized evidence from 15 systematic reviews to investigate which types

of home telemonitoring technologies and forms of interventions are more

effective in reducing mortality and hospital admissions (Kitsiou, Paré, & Jaana, 2015).

9.3.5 Realist Reviews

Realist reviews are theory-driven interpretative reviews developed to inform, enhance, or

supplement conventional systematic reviews by making sense of heterogeneous

evidence about complex interventions applied in diverse contexts in a way that

informs policy decision-making (Greenhalgh, Wong, Westhorp, & Pawson, 2011). They originated from criticisms of positivist systematic reviews

which centre on their “simplistic” underlying assumptions (Oates, 2011). As explained above, systematic reviews

seek to identify causation. Such logic is appropriate for fields like medicine

and education where findings of randomized controlled trials can be aggregated

to see whether a new treatment or intervention does improve outcomes. However,

many argue that it is not possible to establish such direct causal links

between interventions and outcomes in fields such as social policy, management,

and information systems where for any intervention there is unlikely to be a

regular or consistent outcome (Oates, 2011; Pawson, 2006; Rousseau, Manning, & Denyer, 2008).

To circumvent these limitations, Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey, and Walshe (2005)

have proposed a new approach for synthesizing knowledge that seeks to unpack

the mechanism of how “complex interventions” work in particular contexts. The basic research question — what works? — which is usually associated with systematic reviews changes to: what is it

about this intervention that works, for whom, in what circumstances, in what

respects and why? Realist reviews have no particular preference for either

quantitative or qualitative evidence. As a theory-building approach, a realist

review usually starts by articulating likely underlying mechanisms and then

scrutinizes available evidence to find out whether and where these mechanisms

are applicable (Shepperd et al., 2009). Primary studies found in the extant

literature are viewed as case studies which can test and modify the initial

theories (Rousseau et al., 2008).

The main objective pursued in the realist review conducted by Otte-Trojel, de

Bont, Rundall, and van de Klundert (2014) was to examine how patient portals

contribute to health service delivery and patient outcomes. The specific goals

were to investigate how outcomes are produced and, most importantly, how

variations in outcomes can be explained. The research team started with an

exploratory review of background documents and research studies to identify

ways in which patient portals may contribute to health service delivery and

patient outcomes. The authors identified six main ways which represent “educated guesses” to be tested against the data in the evaluation studies. These studies were

identified through a formal and systematic search in four databases between

2003 and 2013. Two members of the research team selected the articles using a

pre-established list of inclusion and exclusion criteria and following a

two-step procedure. The authors then extracted data from the selected articles

and created several tables, one for each outcome category. They organized

information to bring forward those mechanisms where patient portals contribute

to outcomes and the variation in outcomes across different contexts.

9.3.6 Critical Reviews

Lastly, critical reviews aim to provide a critical evaluation and interpretive analysis of existing

literature on a particular topic of interest to reveal strengths, weaknesses,

contradictions, controversies, inconsistencies, and/or other important issues

with respect to theories, hypotheses, research methods or results (Baumeister & Leary, 1997; Kirkevold, 1997). Unlike other review types, critical reviews

attempt to take a reflective account of the research that has been done in a

particular area of interest, and assess its credibility by using appraisal

instruments or critical interpretive methods. In this way, critical reviews

attempt to constructively inform other scholars about the weaknesses of prior

research and strengthen knowledge development by giving focus and direction to

studies for further improvement (Kirkevold, 1997).

Kitsiou, Paré, and Jaana (2013) provide an example of a critical review that assessed the

methodological quality of prior systematic reviews of home telemonitoring

studies for chronic patients. The authors conducted a comprehensive search on

multiple databases to identify eligible reviews and subsequently used a

validated instrument to conduct an in-depth quality appraisal. Results indicate

that the majority of systematic reviews in this particular area suffer from

important methodological flaws and biases that impair their internal validity

and limit their usefulness for clinical and decision-making purposes. To this

end, they provide a number of recommendations to strengthen knowledge

development towards improving the design and execution of future reviews on

home telemonitoring.

9.4 Summary

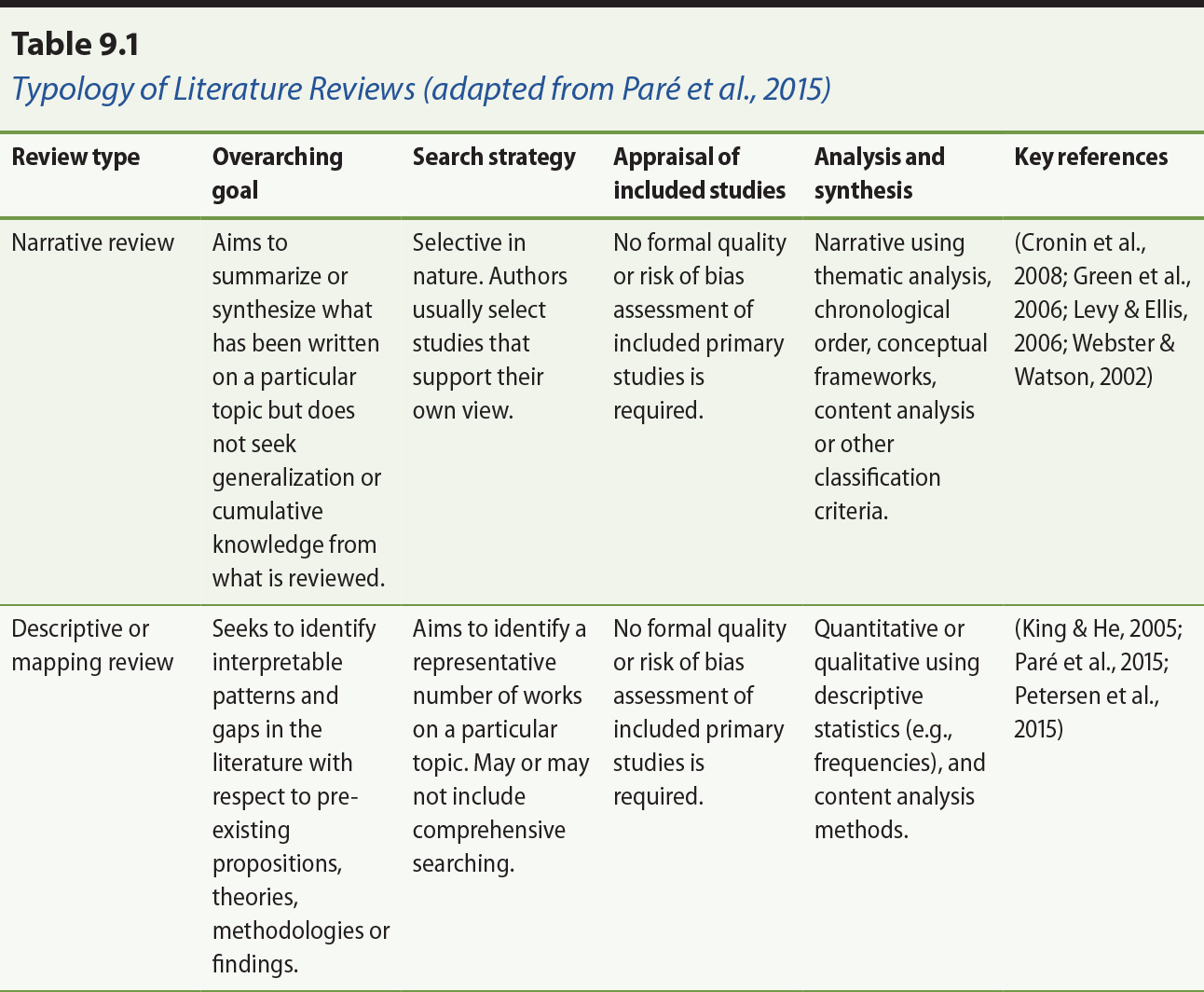

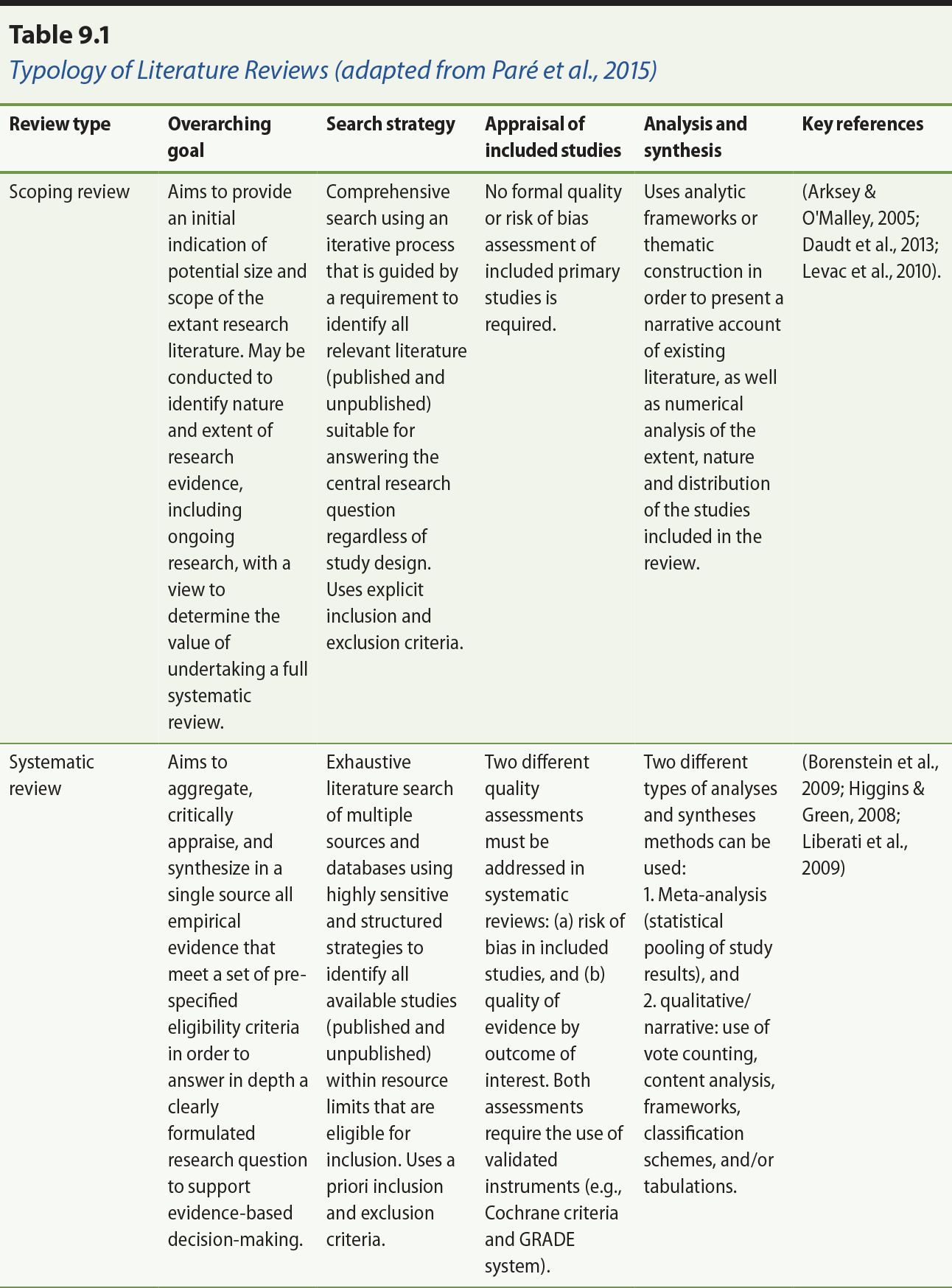

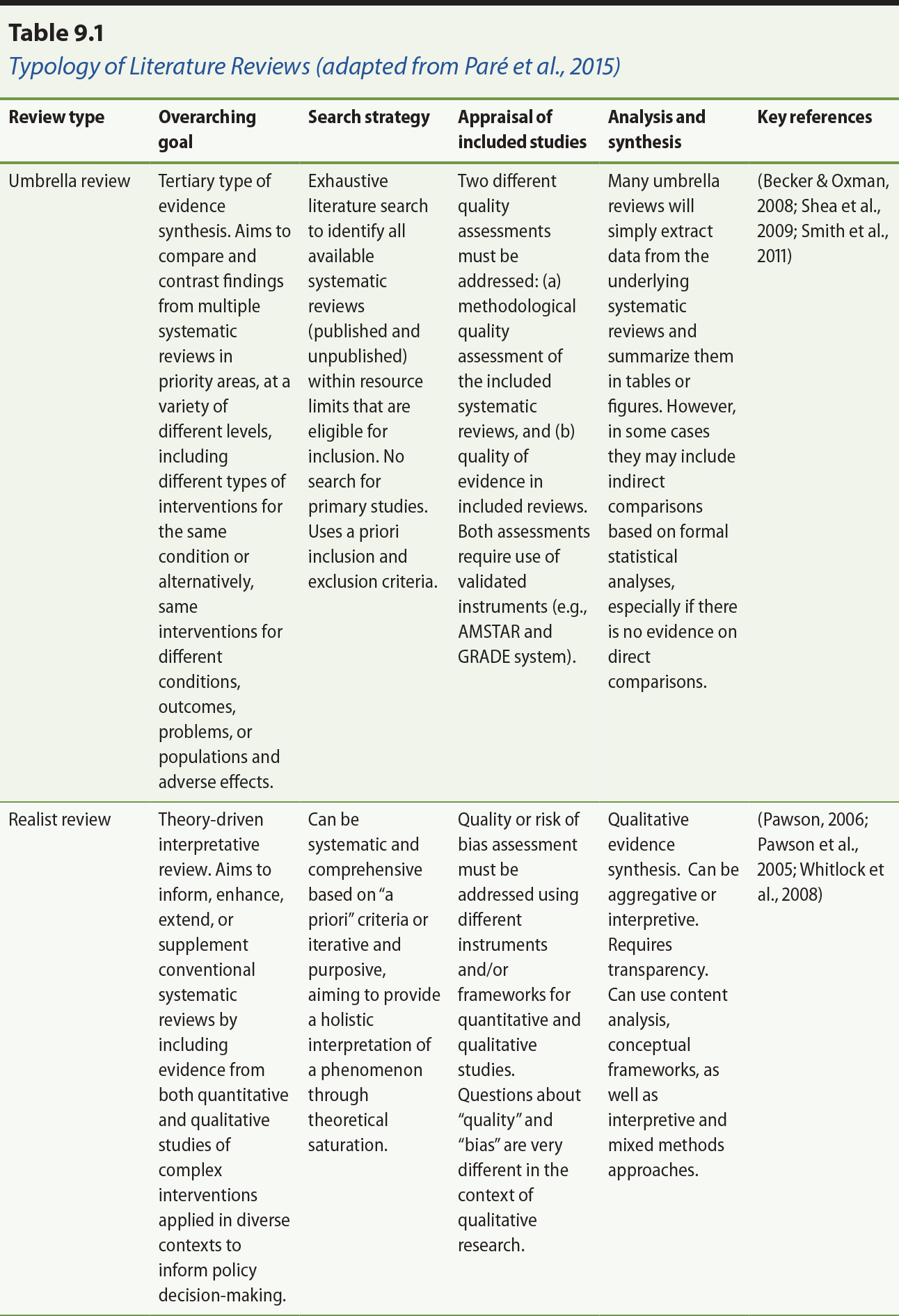

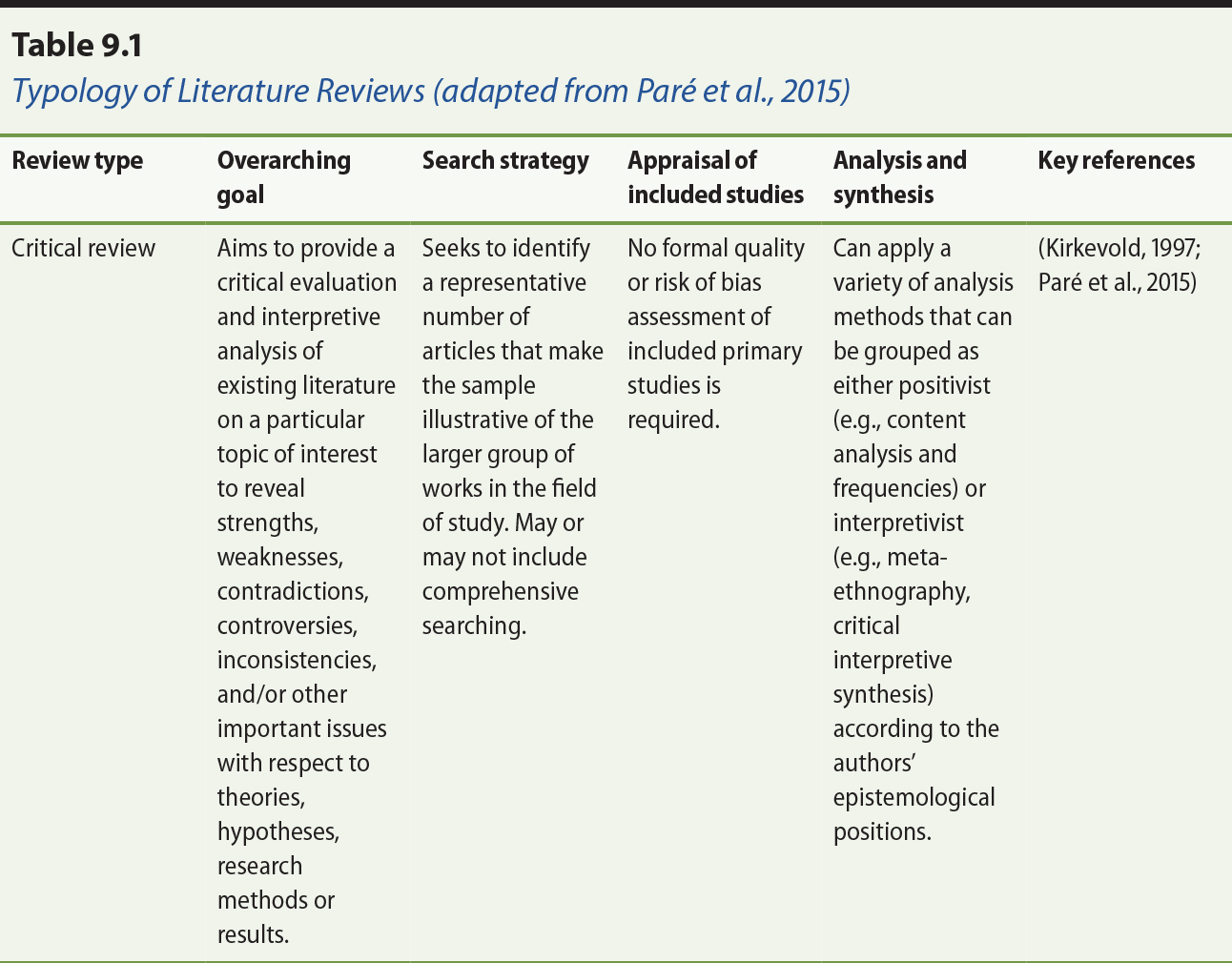

Table 9.1 outlines the main types of literature reviews that were described in

the previous sub-sections and summarizes the main characteristics that

distinguish one review type from another. It also includes key references to

methodological guidelines and useful sources that can be used by eHealth

scholars and researchers for planning and developing reviews.

. From “Synthesizing information systems knowledge: A typology of literature reviews,” by G. Paré, M. C. Trudel, M. Jaana, and S. Kitsiou, 2015, (2), p. 187. Adapted with permission.

As shown in Table 9.1, each review type addresses different kinds of research

questions or objectives, which subsequently define and dictate the methods and

approaches that need to be used to achieve the overarching goal(s) of the

review. For example, in the case of narrative reviews, there is greater

flexibility in searching and synthesizing articles (Green et al., 2006).

Researchers are often relatively free to use a diversity of approaches to

search, identify, and select relevant scientific articles, describe their

operational characteristics, present how the individual studies fit together,

and formulate conclusions. On the other hand, systematic reviews are

characterized by their high level of systematicity, rigour, and use of explicit

methods, based on an “a priori” review plan that aims to minimize bias in the analysis and synthesis process

(Higgins & Green, 2008). Some reviews are exploratory in nature (e.g., scoping/mapping

reviews), whereas others may be conducted to discover patterns (e.g.,

descriptive reviews) or involve a synthesis approach that may include the

critical analysis of prior research (Paré et al., 2015). Hence, in order to select the most appropriate type of review,

it is critical to know before embarking on a review project, why the research

synthesis is conducted and what type of methods are best aligned with the

pursued goals.

9.5 Concluding Remarks

In light of the increased use of evidence-based practice and research generating

stronger evidence (Grady et al., 2011; Lyden et al., 2013), review articles

have become essential tools for summarizing, synthesizing, integrating or

critically appraising prior knowledge in the eHealth field. As mentioned

earlier, when rigorously conducted review articles represent powerful

information sources for eHealth scholars and practitioners looking for

state-of-the-art evidence. The typology of literature reviews we used herein

will allow eHealth researchers, graduate students and practitioners to gain a

better understanding of the similarities and differences between review types.

We must stress that this classification scheme does not privilege any specific

type of review as being of higher quality than another (Paré et al., 2015). As explained above, each type of review has its own strengths

and limitations. Having said that, we realize that the methodological rigour of

any review — be it qualitative, quantitative or mixed — is a critical aspect that should be considered seriously by prospective

authors. In the present context, the notion of rigour refers to the reliability

and validity of the review process described in section 9.2. For one thing, reliability is related to the reproducibility of the review process and steps, which is

facilitated by a comprehensive documentation of the literature search process,

extraction, coding and analysis performed in the review. Whether the search is

comprehensive or not, whether it involves a methodical approach for data

extraction and synthesis or not, it is important that the review documents in

an explicit and transparent manner the steps and approach that were used in the

process of its development. Next, validity characterizes the degree to which the review process was conducted

appropriately. It goes beyond documentation and reflects decisions related to

the selection of the sources, the search terms used, the period of time

covered, the articles selected in the search, and the application of backward

and forward searches (vom Brocke et al., 2009). In short, the rigour of any

review article is reflected by the explicitness of its methods (i.e.,

transparency) and the soundness of the approach used. We refer those interested

in the concepts of rigour and quality to the work of Templier and Paré (2015) which offers a detailed set of methodological guidelines for conducting

and evaluating various types of review articles.

To conclude, our main objective in this chapter was to demystify the various

types of literature reviews that are central to the continuous development of

the eHealth field. It is our hope that our descriptive account will serve as a

valuable source for those conducting, evaluating or using reviews in this

important and growing domain.

References

Ammenwerth, E., & de Keizer, N. (2004). An inventory of evaluation studies of information

technology in health care. Trends in evaluation research, 1982-2002. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 44(1), 44–56.

Anderson, S., Allen, P., Peckham, S., & Goodwin, N. (2008). Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the

commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Research Policy and Systems, 6(7), 1–12. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-6-7

Archer, N., Fevrier-Thomas, U., Lokker, C., McKibbon, K. A., & Straus, S. E. (2011). Personal health records: a scoping review. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association, 18(4), 515–522.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32.

Bandara, W., Miskon, S., & Fielt, E. (2011). A systematic, tool-supported method for conducting literature reviews in

information systems. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on

Information Systems (ECIS 2011), June 9 to 11, Helsinki, Finland.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of General Psychology, 1(3), 311–320.

Becker, L. A., & Oxman, A. D. (2008). Overviews of reviews. In J. P. T. Higgins & S. Green (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (pp. 607–631). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Cook, D. J., Mulrow, C. D., & Haynes, B. (1997). Systematic reviews: Synthesis of best evidence for clinical

decisions. Annals of Internal Medicine, 126(5), 376–380.

Cooper, H., & Hedges, L. V. (2009). Research synthesis as a scientific process. In H. Cooper,

L. V. Hedges, & J. C. Valentine (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (2nd ed., pp. 3–17). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cooper, H. M. (1988). Organizing knowledge syntheses: A taxonomy of literature

reviews. Knowledge in Society, 1(1), 104–126.

Cronin, P., Ryan, F., & Coughlan, M. (2008). Undertaking a literature review: a step-by-step approach. British Journal of Nursing, 17(1), 38–43.

Darlow, S., & Wen, K. Y. (2015). Development testing of mobile health interventions for

cancer patient self-management: A review. Health Informatics Journal (online before print). doi: 10.1177/1460458215577994

Daudt, H. M., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large,

inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, 48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

Davies, P. (2000). The relevance of systematic reviews to educational policy and

practice. Oxford Review of Education, 26(3-4), 365–378.

Deeks, J. J., Higgins, J. P. T., & Altman, D. G. (2008). Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In J. P. T.

Higgins & S. Green (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (pp. 243–296). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Deshazo, J. P., Lavallie, D. L., & Wolf, F. M. (2009). Publication trends in the medical informatics literature:

20 years of “Medical Informatics” in MeSH. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 9, 7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-7

Dixon-Woods, M., Agarwal, S., Jones, D., Young, B., & Sutton, A. (2005). Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review

of possible methods. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 10(1), 45–53.

Finfgeld-Connett, D., & Johnson, E. D. (2013). Literature search strategies for conducting

knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(1), 194–204.

Grady, B., Myers, K. M., Nelson, E. L., Belz, N., Bennett, L., Carnahan, L., . .

. Guidelines Working Group. (2011). Evidence-based practice for telemental

health. Telemedicine Journal and E Health, 17(2), 131–148.

Green, B. N., Johnson, C. D., & Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed

journals: secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 5(3), 101–117.

Greenhalgh, T., Wong, G., Westhorp, G., & Pawson, R. (2011). Protocol–realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: evolving standards (RAMESES). BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 115.

Gurol-Urganci, I., de Jongh, T., Vodopivec-Jamsek, V., Atun, R., & Car, J. (2013). Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare

appointments. Cochrane Database System Review, 12, CD007458. doi: 10.1002/14651858

Hart, C. (1998). Doing a literature review: Releasing the social science research imagination. London: SAGE Publications.

Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (Eds.). (2008). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Cochrane book series. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Jesson, J., Matheson, L., & Lacey, F. M. (2011). Doing your literature review: traditional and systematic techniques. Los Angeles & London: SAGE Publications.

King, W. R., & He, J. (2005). Understanding the role and methods of meta-analysis in IS

research. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16, 1.

Kirkevold, M. (1997). Integrative nursing research — an important strategy to further the development of nursing science and nursing

practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(5), 977–984.

Kitchenham, B., & Charters, S. (2007). Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in

software engineering. EBSE Technical Report Version 2.3. Keele & Durham, UK: Keele University & University of Durham.

Kitsiou, S., Paré, G., & Jaana, M. (2013). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of home telemonitoring

interventions for patients with chronic diseases: a critical assessment of

their methodological quality. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(7), e150.

Kitsiou, S., Paré, G., & Jaana, M. (2015). Effects of home telemonitoring interventions on patients with

chronic heart failure: an overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(3), e63.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69.

Levy, Y., & Ellis, T. J. (2006). A systems approach to conduct an effective literature

review in support of information systems research. Informing Science, 9, 181–211.

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., … Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that

evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), W-65.

Lyden, J. R., Zickmund, S. L., Bhargava, T. D., Bryce, C. L., Conroy, M. B.,

Fischer, G. S., . . . McTigue, K. M. (2013). Implementing health information

technology in a patient-centered manner: Patient experiences with an online

evidence-based lifestyle intervention. Journal for Healthcare Quality, 35(5), 47–57.

Mickan, S., Atherton, H., Roberts, N. W., Heneghan, C., & Tilson, J. K. (2014). Use of handheld computers in clinical practice: a

systematic review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 14, 56.

Moher, D. (2013). The problem of duplicate systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 347(5040). doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5040

Montori, V. M., Wilczynski, N. L., Morgan, D., Haynes, R. B., & Hedges, T. (2003). Systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study of location and

citation counts. BMC Medicine, 1, 2.

Mulrow, C. D. (1987). The medical review article: state of the science. Annals of Internal Medicine, 106(3), 485–488. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-106-3-485

Oates, B. J. (2011). Evidence-based information systems: A decade later.Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems. Retrieved from http://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1221&context=ecis2011

Okoli, C., & Schabram, K. (2010). A guide to conducting a systematic literature review of

information systems research. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Otte-Trojel, T., de Bont, A., Rundall, T. G., & van de Klundert, J. (2014). How outcomes are achieved through patient portals:

a realist review. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association, 21(4), 751–757.

Paré, G., Trudel, M.-C., Jaana, M., & Kitsiou, S. (2015). Synthesizing information systems knowledge: A typology of

literature reviews. Information & Management, 52(2), 183–199.

Patsopoulos, N. A., Analatos, A. A., & Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2005). Relative citation impact of various study designs

in the health sciences. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293(19), 2362–2366.

Paul, M. M., Greene, C. M., Newton-Dame, R., Thorpe, L. E., Perlman, S. E.,

McVeigh, K. H., & Gourevitch, M. N. (2015). The state of population health surveillance using

electronic health records: A narrative review. Population Health Management, 18(3), 209–216.

Pawson, R. (2006). Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. London: SAGE Publications.

Pawson, R., Greenhalgh, T., Harvey, G., & Walshe, K. (2005). Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 10(Suppl 1), 21–34.

Petersen, K., Vakkalanka, S., & Kuzniarz, L. (2015). Guidelines for conducting systematic mapping studies in

software engineering: An update. Information and Software Technology, 64, 1–18.

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide: Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Co.

Rousseau, D. M., Manning, J., & Denyer, D. (2008). Evidence in management and organizational science:

Assembling the field’s full weight of scientific knowledge through syntheses. The Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 475–515.

Rowe, F. (2014). What literature review is not: diversity, boundaries and

recommendations. European Journal of Information Systems, 23(3), 241–255.

Shea, B. J., Hamel, C., Wells, G. A., Bouter, L. M., Kristjansson, E., Grimshaw,

J., … Boers, M. (2009). AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality

of systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1013–1020.

Shepperd, S., Lewin, S., Straus, S., Clarke, M., Eccles, M. P., Fitzpatrick, R.,

. . . Sheikh, A. (2009). Can we systematically review studies that evaluate

complex interventions? PLoS Medicine, 6(8), e1000086.

Silva, B. M., Rodrigues, J. J., de la Torre Díez, I., López-Coronado, M., & Saleem, K. (2015). Mobile-health: A review of current state in 2015. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 56, 265–272.

Smith, V., Devane, D., Begley, C., & Clarke, M. (2011). Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic

reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 15.

Sylvester, A., Tate, M., & Johnstone, D. (2013). Beyond synthesis: re-presenting heterogeneous research literature. Behaviour & Information Technology, 32(12), 1199–1215.

Templier, M., & Paré, G. (2015). A framework for guiding and evaluating literature reviews. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 37(6), 112–137.

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research

in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45.

vom Brocke, J., Simons, A., Niehaves, B., Riemer, K., Plattfaut, R., & Cleven, A. (2009). Reconstructing the giant: on the importance of rigour in documenting the

literature search process. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on

Information Systems (ECIS 2009), Verona, Italy.

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a

literature review. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 26(2), 11.

Whitlock, E. P., Lin, J. S., Chou, R., Shekelle, P., & Robinson, K. A. (2008). Using existing systematic reviews in complex systematic

reviews. Annals of Internal Medicine, 148(10), 776–782.

Annotate

EPUB