Skip to main content

Notes

table of contents

Chapter 5

eHealth Economic Evaluation Framework

Francis Lau

5.1 Introduction

Increasingly, healthcare organizations are challenged to demonstrate the worth

of eHealth investments with respect to their economic return. Over the years,

different approaches have been applied to determine the value of eHealth

investments such as the financial benefit, cost-effectiveness and

quality-adjusted life years gained. Despite the work done to date, there is

still limited evidence on the economic return associated with the myriad of

eHealth systems deployed. This available evidence is often mixed as to whether

eHealth can demonstrate a positive return on the investment or not. Moreover,

the methodological rigour of some evaluation studies is questionable.

In 2013, Bassi and Lau published a scoping review of primary studies on the

economic evaluation of HIS or health information systems (2013). Based on 33 high-quality HIS economic evaluation studies published between 2000 and 2012 we reported on the

key components of an HIS economic evaluation study, the current state of evidence on economic return of HIS, and a set of guidance criteria for conducting HIS economic evaluation studies. Drawing on the review findings, we proposed an

economic evaluation classification scheme that is the basis of the eHealth

Economic Evaluation Framework described in this chapter.

This chapter describes an eHealth Economic Evaluation Framework based on our

scoping review findings and related best practices in economic evaluation

literature. The chapter covers the underlying conceptual foundations and the

six dimensions of our framework, guidance on its potential use and implications

for healthcare organizations.

5.2 Conceptual Foundations

Different economic evaluation approaches for eHealth have been described in the

literature. They vary according to the analytical methods applied, the health

consequences being considered, and whether it involves a synthesis of multiple

studies. The quality of eHealth economic evaluation studies also varies

depending on the methodological rigour applied in their design, analysis and

reporting. The type and quality of eHealth economic evaluation studies are

described below.

5.2.1 Types of Economic Evaluation in eHealth

Economic evaluation is the comparative analysis of alternative interventions

with respect to their costs and consequences. Economic evaluation can be based

on empirical trials, mathematical models, or a combination of both. The types

of economic evaluation studies found in eHealth literature include cost-benefit

analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, and cost-utility analysis. Other

variants are cost-minimization analysis, cost-consequence analysis, input cost

analysis, and cost-related outcome analysis. These types of economic evaluation

are defined below (Roberts, 2006).

- Cost-benefit analysis – examines both costs and consequences in monetary terms.

- Cost-effectiveness analysis – examines costs and a single consequence in its natural unit such as hospital length of stay in days or frequency of adverse events as a percentage.

- Cost-utility analysis – examines costs and a single consequence in the form of a health-related quality of life measure such as quality-adjusted life years.

- Cost-consequence analysis – examines the costs and multiple consequences in their natural units without aggregation into a single consequence.

- Cost-minimization analysis – examines the least costly consequence among alternatives with equivalent consequences.

- Input cost analysis – examines the costs of all alternatives but not their consequences.

- Cost-related outcome analysis – examines the consequences of all alternatives in monetary terms but not the input costs incurred.

When the economic analysis involves the comparison of both the costs and

consequences, it is considered a full economic evaluation. Cost-benefit,

cost-effectiveness, cost-utility, and cost-consequence analyses are examples of

full economic evaluation. If the analysis involves only the costs (e.g., input

cost analysis) or consequences (e.g., cost-related outcome analysis), it is

considered a partial or one-sided economic evaluation. Cost-minimization is a

form of input cost analysis since it assumes all of the consequences are

equivalent and therefore the focus is on the least costly alternative.

In the eHealth literature, sometimes the term “benefit” is used to include different types of consequences which may be non-monetary in

nature. An example is the term “benefits evaluation” where the benefits can be in dollar terms or in some other units such as

hospital length of stay in days or number of adverse events in a given time

period. To avoid confusion it is important to describe the type of economic

analysis used and the nature of the benefits involved.

5.2.2 Quality of eHealth Economic Evaluation Studies

Different criteria for assessing the quality of economic evaluation studies in

terms of their design, analysis and reporting have been published in the

literature. In this section, we briefly describe the quality assessment

criteria from our scoping review and the Consolidated Health Economic

Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) publication guidelines (Husereau et al., 2013) as two ways to enhance the

rigour of our eHealth Economic Evaluation Framework. These are described in

more detail in chapter 14 under methodological considerations and best practice

guidelines.

Ten quality criteria derived from four literature sources were used in our

scoping review to assess the methodological quality of the selected HIS economic evaluation studies (Drummond & Jefferson, 1996; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination [CRD], 2009; Evers, Goossens, de Vet, van Tulder, & Ament, 2005; Machado, Iskedjian, & Einarson, 2006). Each criterion scores between 0 and 1, from not stated,

somewhat stated, to clearly stated, for a maximum score of 10 as having the

highest quality. These criteria are listed below:

- Is there a research question or definition of the study aim?

- Are the primary outcome measures stated?

- Is the study sample provided and described?

- Is the HIS being evaluated described?

- Is the study time horizon stated?

- Are the data collection methods described?

- Are the analytical methods described?

- Are the results clearly reported with caveats where needed?

- Do the conclusions follow from the study question/objective?

- Are generalizability issues addressed along with limitations?

The CHEERS guidelines were published in 2013 (Husereau et al., 2013) by the Good Reporting

Practices Task Force of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and

Outcomes Research (ISPOR). The guidelines are recommendations for optimized reporting of health economic

evaluation studies. They were derived from previous systemic reviews and

surveys of task force members, followed by two rounds of Delphi process that

reduced an initial list of 44 candidate reporting items to 24 items with

accompanying recommendations in a checklist format.

- Title and abstract – two items on having a title that identifies the study as an economic evaluation, and a structured summary of objectives, perspective, setting, methods, results and conclusions.

- Introduction – one item on study context and objectives, including its policy and practice relevance.

- Methods – 14 items on target populations, setting, perspective, comparators, time horizon, discount rate, choice of health outcomes, measurement of effectiveness, measurement and valuation of preference-based outcomes, approaches for estimating resources and costs, currency and conversion, model choice, assumptions, and analytic methods.

- Results – four items on study parameters, incremental costs and outcomes, describing uncertainty, and describing heterogeneity.

- Discussion – one item on findings, limitations, generalizability and current knowledge.

- Others – two items on the source of study funding and conflicts of interest.

5.3 Framework Dimensions

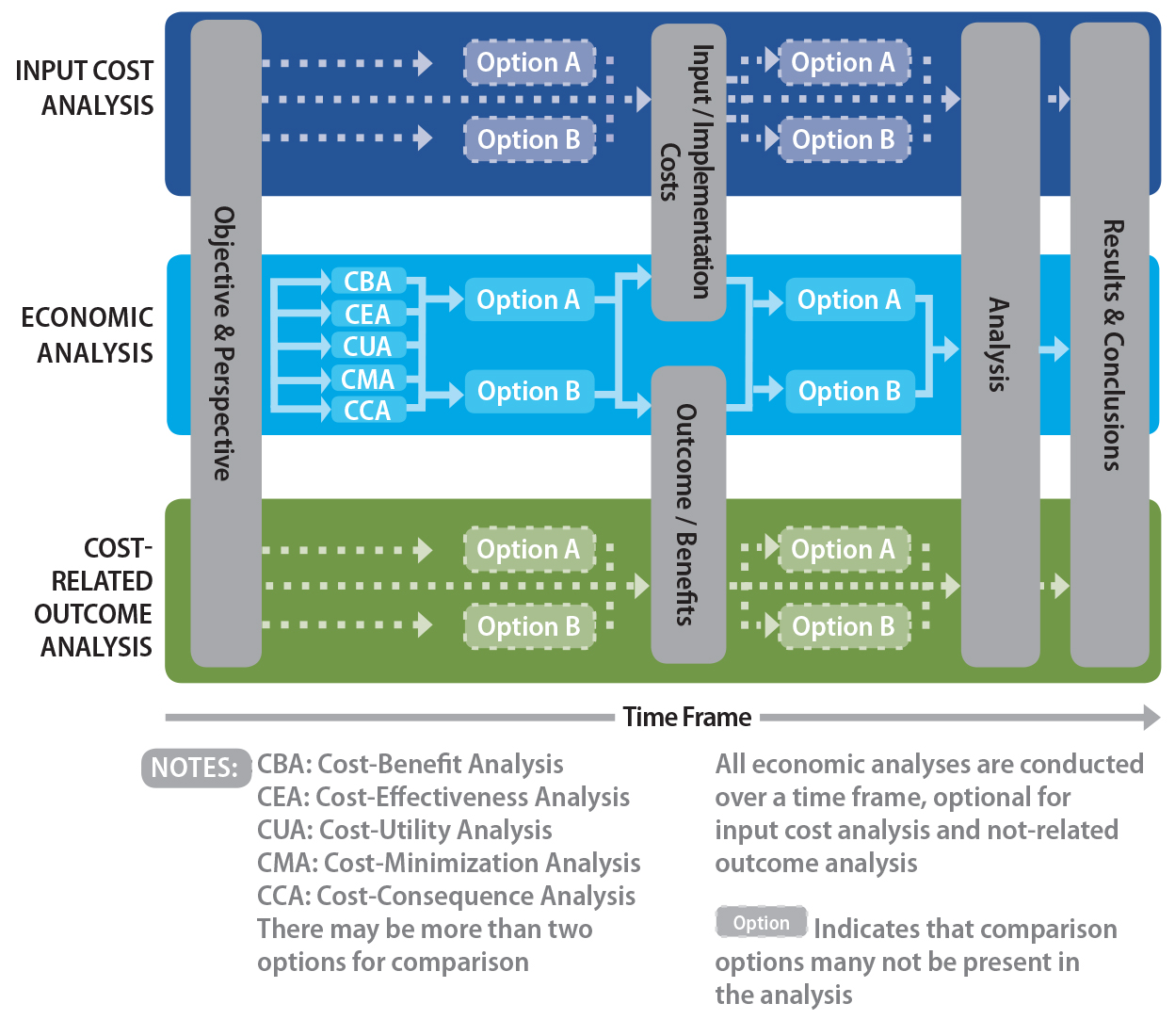

The eHealth Economic Evaluation Framework is derived from our scoping review of HIS economic evaluation studies. Its intent is to provide a classification scheme

for the different approaches used in eHealth economic evaluation studies. The

framework is made up of six components: having a perspective, options, time

frame, costs, outcomes, and method of analyzing/comparing options. These

components are shown in Figure 5.1 and described below.

Figure 5.1. eHealth economic evaluation framework.

Note.From “Measuring value for money: A scoping review on economic evaluation of health

information systems,” by J. Bassi and F. Lau, 2013, Journal of American Medical Informatics Association, 20(4), p. 793. Copyright 2013 by Oxford University Press, on behalf of American

Medical Informatics Association. Reprinted with permission.

5.3.1 Perspective

Perspective refers to the point of view under which an eHealth economic

evaluation is being conducted. It is an important component in the framework

because the costs and consequences accrued can affect different parts of the

healthcare system. As such, the economic return of an eHealth system is

dependent upon who makes the decision, who incurs the costs and who benefits

from the consequences. For instance, care providers mandated by the government

to adopt an electronic prescription tracking system may perceive it as an added

cost that only benefits the government by controlling their practice. The

perspectives considered in our framework are those of the individual,

organization, payer, and society at large. These are defined below:

- Individual – the person affected such as the provider, patient or caregiver. The effect may involve a change in the person’s expenditures, routines and/or health conditions.

- Organization – the group affected such as the health region, professional association, or patient advocacy where multiple individuals within the group are affected in similar ways.

- Payer – the group that finances the healthcare service such as the government or private insurers. The effect may involve a change in the group’s cost of providing the service.

- Society – the general public affected such as the residents in a geographic region or the entire population of a country. The effect may involve a change to the overall financing of the healthcare system and/or the health status of the population.

5.3.2 Options

Options are the alternative eHealth systems being considered. It is important to

clearly define each eHealth system option since they often perform multiple

functions and can be adopted for different reasons by different organizations.

Also, the behaviour of the system can evolve over time as users become more

experienced in using it to support their work. Increasingly, eHealth systems

are combined with other interventions to enhance the intended effects. For

these reasons, the features within each of these options must be clearly

defined for meaningful comparisons to be made. The types of options reported in

the eHealth economic evaluation literature are with or without the system, pre-

or post-implementation, types of systems, levels of systems, different time

points, and different sites. These options are defined below:

- With or without the system – one or more eHealth system options and a status quo with no system

- Pre- or post-implementation – before and after the adoption of an eHealth system

- Types of systems –different eHealth system options with the same or similar functions

- Levels of systems – extent of eHealth systems and/or functions adopted in the organization

- Different time points – the same eHealth system at different points in time

- Different sites – the same eHealth system adopted in different organizations or locations

Two important aspects of options are the status quo and opportunity cost. Status

quo refers to the costs and consequences of the current situation without

adopting any eHealth systems, or a default “do nothing” position. Opportunity cost refers to the foregone benefit as a result of

selecting a given eHealth system option. Status quo and opportunity cost are

important in eHealth investment decisions when there are limited resources

among competing priorities. For example, a healthcare organization addressing

patient medication safety has to decide whether its existing rate of medication

errors, or the status quo, is acceptable or needs improvement with an

electronic surveillance system as an option. Similarly, an organization wishing

to adopt an EMR system to improve its overall care delivery may consider the opportunity cost

by asking whether the EMR investment can be better spent elsewhere with comparable effect.

5.3.3 Time Frame

Time frame refers to the length of time for which the costs and consequences of

an eHealth system are accrued. One must allow for sufficient time to ensure all

of the relevant costs are captured and the consequences are realized as they

can accrue differently over time. Often there is a time lag before the

consequences, such as a reduction in the rate of adverse events, can be

realized after the adoption of an eHealth system. For pragmatic reasons,

studies based on empirical data for costs and consequences tend to use shorter

time frames, as it is difficult and costly to collect data for a long period.

Studies based on mathematical modelling tend to have longer time frames since

there is little added effort to predict long-term trends. The time frames

reported in eHealth economic evaluation literature are less than one year, one

to five years, six to 10 years, and greater than 10 years. They are defined

below:

- Less than one year – typically for small-scale studies where empirical data on costs and consequences from an eHealth system or intervention are collected over a short time period such as three to six months for comparison. Sometimes the cost and/or consequence are extrapolated to an annual period such as estimated cost savings from an EMR system per year.

- One to five years – the most common time periods used are between one and five years in duration to capture the costs, consequences, or both, that are accrued. Sometimes different time periods are used to collect the accrued costs and consequences. For instance one may extract the historical costs for EMR adoption over one year then estimate the return on investment over a five-year period.

- Six to 10 years – typically for modelling studies where the costs and consequences are projected over a six- to 10-year period. The data can be based on historical, prospective, estimated or combined sources.

- Greater than 10 years – mostly for predicting the long-term consequences of an eHealth system such as the cumulative economic impact of a diabetes management system expected over a 40-year period.

- Multiple time points – typically in studies where different types of costs and consequences are captured across multiple time periods depending on the availability of the data.

Note that the time period covered in an economic evaluation study is different

from the time it takes to conduct the study itself. For instance, the economic

return of a computerized provider order entry system (CPOE) may be determined over a 5-year period to ensure all of the costs incurred are

captured and the CPOE is sufficiently stabilized to realize an improvement in ordering medications.

Yet the study itself may only take two or three months to collect and analyze

the data if it is retrospective in nature or if predictive modelling is used to

estimate the effect over a five-year period based on historical data.

5.3.4 Input Costs

Input costs are the amounts of money spent in the adoption of an eHealth system.

The types of costs reported in the eHealth economic evaluation literature are

one-time direct costs, ongoing direct costs, and ongoing indirect costs. They

are defined below.

- One-time direct costs – expenditures incurred in order to implement the system. They include such items as hardware equipment, software licences, application development/customization, data conversion, system configuration, training, user and technical support.

- Ongoing direct costs – recurrent expenditures to operate the system after its implementation. They include such items as hardware and software maintenance, system upgrades, technical and support staffing, ongoing training, and related professional services (e.g., system audits).

- Ongoing indirect costs – recurrent expenditures related to the system that is allocated by the organization after its implementation. They include prorated expenditures such as managing IT-related privacy, security, policy and help desk, and changes in staff workload.

Intangible costs are another type of cost that is mentioned in the economic

evaluation literature. Intangible costs refer to things that are unquantifiable

or difficult to measure. Examples of intangible costs in the adoption of an

eHealth system are a change in staff morale and patient anxiety before, during

and after the implementation of an EMR as they learn to work with the new system. Intangible costs are seldom

addressed in eHealth economic evaluations. One approach is to estimate

intangible costs as a type of input or outcome such as the quality of staff

work life in terms of productivity before or after the adoption of an EMR.

5.3.5 Outcomes

Outcomes refer to the consequences from adopting an eHealth system. There are

different types of outcomes reported in the eHealth economic evaluation

literature. These outcomes may be financial or non-financial in nature, and can

be derived from empirical data, projections or both. Financial outcomes include

changes in revenues, labour and supply costs, and capital costs expressed in

monetary units. Non-financial outcomes include changes in resource utilization

and health outcomes in their natural units. These types of consequences are

outlined below. Note that only tangible outcomes are considered here.

- Revenues – money generated from billing and payment of patient care service provision supported by the eHealth system, and change in such financial arrangements as the reimbursement rates, accounts receivable days and payer mix for service claims.

- Labour and supply cost savings – change in staffing costs due to altered productivity associated with the eHealth system such as data entry, charting, communication and reporting, and change in supply costs such as the amount of stocked materials and goods consumed.

- Capital cost savings – change in capital expenditures for such items as facilities, equipment and technology due to the adoption of an eHealth system.

- Resource utilization – change in healthcare resource usage such as the volume of laboratory and radiology tests, medications and other diagnostic/interventional procedures consumed.

- Health outcomes – change in patients’ conditions and clinical events such as one’s physiologic status, or the number of medical errors and adverse events reported.

5.3.6 Comparison of Options

Comparison of options refers to the analytical methods used to determine the

return on investment for each eHealth system option being considered. Different

methods have been reported in the eHealth economic evaluation literature. They

include accounting, statistical, and operations research methods that draw on

different types of data as their input sources. These are defined below.

- Data sources – tabulation of cost and outcome data as the input data sources, based on historical records, expert estimates, model projections, or combinations.

- Accounting – measuring the financial performance of each option, which includes the outcome measures, time value of money, uncertainty and risks. Examples of outcome measures are incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, payback, net present value, operating margin and quality-adjusted life years. Examples of time value of money are discounting, inflation, depreciation and amortization. Examples of handling uncertainty and risks are sensitivity and scenarios analysis.

- Statistics – measuring the financial performance of each option based on statistical techniques such as linear/logistic regression, general linear modelling and testing for group differences.

- Operations research – measuring the financial performance of each option based on operational research methods such as panel regression, parametric cost analysis, stochastic frontier analysis and simulation modelling.

5.4 Framework Usage

The eHealth Economic Evaluation Framework was derived from a scoping review of

33 high-quality HIS economic evaluation studies published between 2000 and 2012. The review provides

a rich source of published studies, methods, measures, and lessons that can

serve as guidance for designing, analyzing and reporting eHealth economic

evaluation studies. The potential usage and implications of this framework

based on the six components reported in the review are described below.

5.4.1 Potential Usage

For the 33 HIS studies in the review, 12 were considered full economic evaluations as they

included all six framework components. Of these, six were on cost-benefit, two

were on cost-effectiveness, two on cost-consequence, and one on cost-utility.

For the remaining studies, 16 were on cost-related outcomes, and five on input

costs. As for the categories described under each of the six framework

components, their patterns of usage among the 33 HIS studies are tabulated below (for more detail, see Bassi & Lau, 2013).

- Perspective – Most studies (87.9% or 29/33) were based on an organizational perspective, while 12.1% (4/33) were on society, and 3.0% (1/33) each on individual and payer. Note that the total count exceeds 100% as two studies had two perspectives each and therefore were counted twice.

- Time Frame – Over half (54.5% or 18/33) of the studies had time periods of one to five years. Of the remainder, 24.2% (8/33) had six to 10 years, 12.1% (4/33) less than one year, and 3.0% (1/33) each for less than six months, greater than 10 years and multiple time points, respectively.

- Options – Close to half (45.5% or 15/33) of the studies had options of with or without the system, while 27.3% (9/33) had pre- and post-implementation options. The remaining were 9.1% (3/33) on different types of options with similar functions, 9.1% for different levels of adoption, and 3.0% (1/33) each for different time points and not defined, respectively.

- Input Costs – 277 measures were reported based mostly on input cost analysis and cost benefit analysis studies. The majority of these measures were one-time direct costs (60.6% or 168/277) with the remaining as ongoing direct costs (32.9% or 91/277). Ongoing indirect costs were seldom mentioned (0.7% or 2/277). Of the 168 one-time direct cost measures, just over one-third (35.1% or 59/168) were for application development and deployment, with the remaining on hardware and software (32.1% or 54/168), initial data collection/conversion (6.5% or 11/168), initial user training (6.0% or 10/168) and other costs. Of the 91 ongoing direct cost measures, close to half were for IT and support staff salaries (25.3% or 23/91) and software licences, maintenance and upgrades (20.0% or 18/91). Many studies also had direct and indirect costs combined into other, overall and total costs.

- Outcomes – 195 measures were reported based mostly on cost-benefit analysis or cost-related outcome analysis studies. Close to half of the measures (46.7% or 91/195) were on resource utilization, mostly for medications (47.3% or 43/91) and laboratory tests (34.1% or 31/91). Other outcome categories include labour savings (17.4% or 34/195), healthcare service provision savings (12.3% or 24/195), and total costs/savings (12.8% or 25/195). Examples of labour savings reported are efficiency and time-related savings. Healthcare service provision savings refer to changes in clinical outcomes and include rates of adverse drug events, patient safety events and disease prevention or management. Total cost savings include such measures as annual cost savings, net benefit and incremental cost effectiveness ratio.

- Comparison of Options – Accounting was the most common method (72.7% or 24/33) used to compare options through such measures as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, return on investment, payback, net present value, net benefit, operating margin, least cost, average cost and cost savings. The estimation methods used to estimate future outcomes included linear/logistic regression (15.2% or 5/33), scenarios analysis (9.1% or 3/33), and general/linear modelling (9.1%). Many studies adjusted for inflation (30.3% or 10/33), discounting (24.2% or 8/33), and amortization/depreciation (12.1% or 4/33). Some studies applied statistical methods to test for differences among groups such as t-test (15.2% or 5/33), analysis of variance (6.1% or 2/33) and chi-square (3.0% or 1/33). Several studies used econometric or financial modelling methods based on simulation (12.1% or 4/33), parametric cost analysis (6.1% or 2/33), stochastic frontier analysis (3.0% or 1/33), and panel regression (3.0% or 1/33). For data sources, close to half (48.5% or 16/33) of the studies used both historical and published costs for comparison, while just over one-tenth (12.1% or 4/33) used historical and estimated costs. The remaining studies (39.4% or 13/33) used historical and estimated costs to project future costs and benefits.

5.5 Implications

The eHealth Economic Evaluation Framework described in this chapter can serve as

a classification scheme for the approaches used to evaluate the economic return

on eHealth system investments. The framework defines the six key components

that should be addressed when designing, analyzing and reporting eHealth

economic evaluation studies. There are four practice implications to be

considered when applying this framework: (a) the type of economic analysis

involved, (b) the use of estimated costs, (c) the importance of incremental

return, and (d) the issue of opportunity cost (Gospodarevskaya & Westbrook, 2014). These are described below.

- Type of economic analysis – From the scoping review we found only 12 studies were considered full economic evaluations with half of them being cost-benefit analysis, while the other types such as cost-utility analysis were rarely seen. The review included 16 cost-related outcome analysis studies that focused mostly on cost savings or cost changes after implementation. However, without knowing the initial costs of implementing the system it is difficult to determine whether the savings were worth the investment. Similarly, there were five studies on input cost analysis, which alone does not reveal the respective return on each option to make an investment decision.

- Estimated costs – Over half of the 33 studies in the review included some type of estimated costs when deriving the input costs or projecting cost-related outcomes. In general, economic evaluation studies that are based on expert opinions, cost avoidance and modelling should be viewed with caution. Expert opinions are subjective in nature and it is often difficult to validate their accuracy. Cost avoidance refers to potential reductions only and these are less convincing than tangible measureable outputs such as actual cost savings in dollars. Modelling studies are hypothetical in nature and may lead to unrealistic forecasts and expectations.

- Marginal return – Within the economics discipline, full economic evaluation is the comparative analysis of options that involves the identification, measurement and valuation of costs and outcomes to determine the incremental difference in costs in relation to difference in outcomes. This is demonstrated through the cost for each additional unit of outcome compared with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). In the review, only two studies applied ICER to determine the incremental return of the investment decision. The remaining studies compared the costs and outcomes for each option, which provides only an average cost-effectiveness ratio.

- Opportunity cost – Related to the notion of incremental return is the opportunity cost, which is the foregone benefit from the alternative use of resources beyond the eHealth system options. As such, the investment decision must demonstrate its economic efficiency by providing better value than the alternative use of resources and associated outcomes, including non-eHealth options.

5.6 Summary

This chapter described the eHealth Economic Evaluation Framework as a

classification scheme to help understand the different approaches used in

eHealth economic evaluation studies. The framework has six components: having a

perspective, options, time frame, input costs, outcomes, and method of

analyzing/comparing options. Best practice guidance does exist for each of the six

framework components and there are quality criteria for assessing such studies

that should be considered. By applying the framework components one can improve

the design, analysis, and reporting of eHealth economic evaluation.

References

Bassi, J., & Lau, F. (2013). Measuring value for money: A scoping review on economic

evaluation of health information systems. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association,20(4), 792–801.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). (2009, January). Systematic reviews —CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York, UK: University of York. Retrieved from http://www.york.ac.uk/crd/guidance

Drummond, M. F., & Jefferson, T. O. (1996). Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic

submissions to the BMJ. British Medical Journal,313(7052), 275–283.

Evers, S., Goossens, M., de Vet, H., van Tulder, M., & Ament, A. (2005). Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of

economic evaluations: Consensus on health economic criteria. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 21(2), 240–250.

Gospodarevskaya, E., & Westbrook, J. I. (2014). Correspondence: Call for discussion about the

framework for categorizing economic evaluations of health information systems

and assessing their quality. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association,21(1), 190–191.

Husereau, D., Drummond, M., Petrou, S., Carswell, C., Moher, D., Greenberg, D., … Loder, E. (2013). Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) – Explanation and elaboration: A report of the ISPOR health economic evaluation publication guidelines good reporting practices task

force. Value in Health,16, 231–250.

Machado, M., Iskedjian, M., & Einarson, T. R. (2006). Quality assessment of published health economic

analyses from South America. Annals of Pharmacotherapy,40(5), 943–949.

Roberts, M. S. (2006). Economic aspects of evaluation. In C. P. Friedman & J. C. Wyatt (Eds.), Evaluation methods in biomedical informatics (2nd ed., pp. 301–337). New York: Springer.

Annotate

EPUB