Skip to main content

Notes

table of contents

Chapter 25

Evaluating Telehealth Interventions

Anthony J. Maeder, Laurence S. Wilson

25.1 Introduction

This chapter discusses an area viewed by many as a “special case” in eHealth evaluations: dealing with usage of telehealth, which is the delivery of healthcare services of a clinical nature where the

provider of the service is remote in location and/or time from the recipient

(such as teleconsultation, or teleradiology). We use the term telehealth intervention to indicate that our focus is on clinical processes (such as diagnosis or

therapy) employing telehealth as a major component of their delivery. This term

implies that the telehealth aspect is overlaid or inserted in a broader

clinical activity or service, of which other components may be achieved by

non-telehealth means.

Within the scope of our discussion, we also include evaluation of projects that

establish and deploy these types of interventions, but not the evaluation of

health services or systems as a whole, within which the interventions are

delivered as one of a set of diverse and often complex interconnected

components. This exclusion applies also to regional and national telehealth

systems which serve multiple purposes and are therefore in the domain of health

enterprise evaluation, rather than directly tractable by analysis methods

intended for clinical services. An approach to such broader analysis is

exemplified by work undertaken in Canada to develop a set of National

Telehealth Outcome Indicators (Scott et al., 2007), which provided a base set

of measurable indicators in the areas of quality, access, acceptability and

costs, for post-implementation service-based evaluations. We also exclude the

evaluation of underlying ICT-based mechanisms and infrastructure, including networks and systems that

transmit and support telehealth such as broadband communications connectivity,

and turnkey videoconferencing or store-and-forward systems, which are able to

be suitably evaluated by application of established technology or information

systems analysis methods.

In the following sections we will first discuss how perspectives on telehealth

can impact philosophically on evaluation approaches, imposing in some cases

limitations and a narrowed view, which can discourage inclusion of a “full spectrum” of potential elements in evaluations. We will identify a wide range of

approaches and associated elements that may be considered appropriate for

telehealth evaluations, drawing predominantly from contributions in the

clinical literature. Next we will link these elements with frameworks for

evaluation that have been suggested by several authors, to demonstrate that the

same elements may be viewed in different combinations and targeting different

evaluation purposes. Finally, we will provide a commentary on practical

constraints and considerations when conducting telehealth evaluations, and

illustrate this with a case study based on a stand-alone intervention project.

25.2 Background

Early work in telehealth was poorly served by inadequate evaluation efforts.

There are several reasons for this deficiency. Emphasis was often placed on the

novelty of the technology or organizational aspects of the intervention,

leading to evaluation of these aspects in preference to others more relevant to

health impacts, and using associated evaluation methods which were often

unfamiliar in clinical settings. A simplistic initial view of telehealth as the

utilization of one of only a few different IT delivery mechanisms (such as video or image transfer), which could be analysed

separately from any human or organizational aspects, reinforced this viewpoint.

Health benefits and health economics gains are typically realized only after a

lengthy period of time, beyond the extent of projects which delivered the

intervention. Consequently, long-term clinical quality of care improvements and

health services efficiency gains have often been regarded as impractical to evaluate. On the other hand, participant experience and

satisfaction is relatively easy to assess, and so many early evaluations incorporated that as a significant component, a trend that has continued.

As noted by Bashshur, Shannon, and Sapci (2005), a dilemma exists as to whether

to evaluate a telehealth intervention as if it were a typical health

intervention coincidentally delivered by telehealth technology, or whether to

treat it as a special type of intervention for the purpose of evaluation,

because it relies on telehealth. A related issue arising is whether

conventional evaluation methods for health interventions generally are

applicable to telehealth interventions, as the first model above would imply,

or whether specific evaluation methods should be developed for telehealth, in

line with the second model. In reality, telehealth interventions are seldom

evaluated without substantial interest in the telehealth aspects, so the second

model has tended to dominate evaluation approaches. Consequently, evaluation

methods designed for eHealth such as STARE-HI and GEP-HI in the clinical process arena, or for technology-based health interventions

more generally such as TAM and UTAUT in the user arena, are often deemed inadequate for telehealth interventions.

25.3 Telehealth Evaluation Approaches

Initial formal contributions in the field proposed flexible approaches

concentrating on case-specific aspects of interest (Bashshur, 1995) or

selective use of generic health services measures. For example, Hailey, Jacobs,

Simpson, and Doze (1999) proposed that evaluation be performed across five

areas: specification, performance measures, outcomes, summary measures, and operational considerations. Cost and workload aspects were identified as an important specific area, warranting careful

development of appropriate analysis methods (Wootton & Hebert, 2001), and these have subsequently been a focus of many studies.

Another important area targeted by many researchers was psychosocialaspects related to users (Stamm, Hudnall, & Perednia, 2000), such as usability and satisfaction. Emphasis was also placed

on the efficacy of diagnostic and management decisions (Hersch et al., 2002) and associated impacts on access and outcomes in telehealth services (Hersch et al., 2006). Furthermore, technical aspects of implementations were also seen as a part of evaluation (Clarke & Thiyagarajan, 2008), in the areas of information capture and display, and information transmission (including statistical analysis and visual quality).

The notion of inferred causality linking the intervention characteristics with observed effects which were

ascribed to telehealth in evaluations was described by Bashshur et al. (2005),

and the influence of medical care process models for unifying the effects of client and provider behaviours and explaining

participation effects and clinical outcomes was advocated by Heinzelmann,

Williams, Lugn, and Kvedar (2005). These two alignments suggest that one

strategy for conducting evaluations is to focus predominantly on the clinical

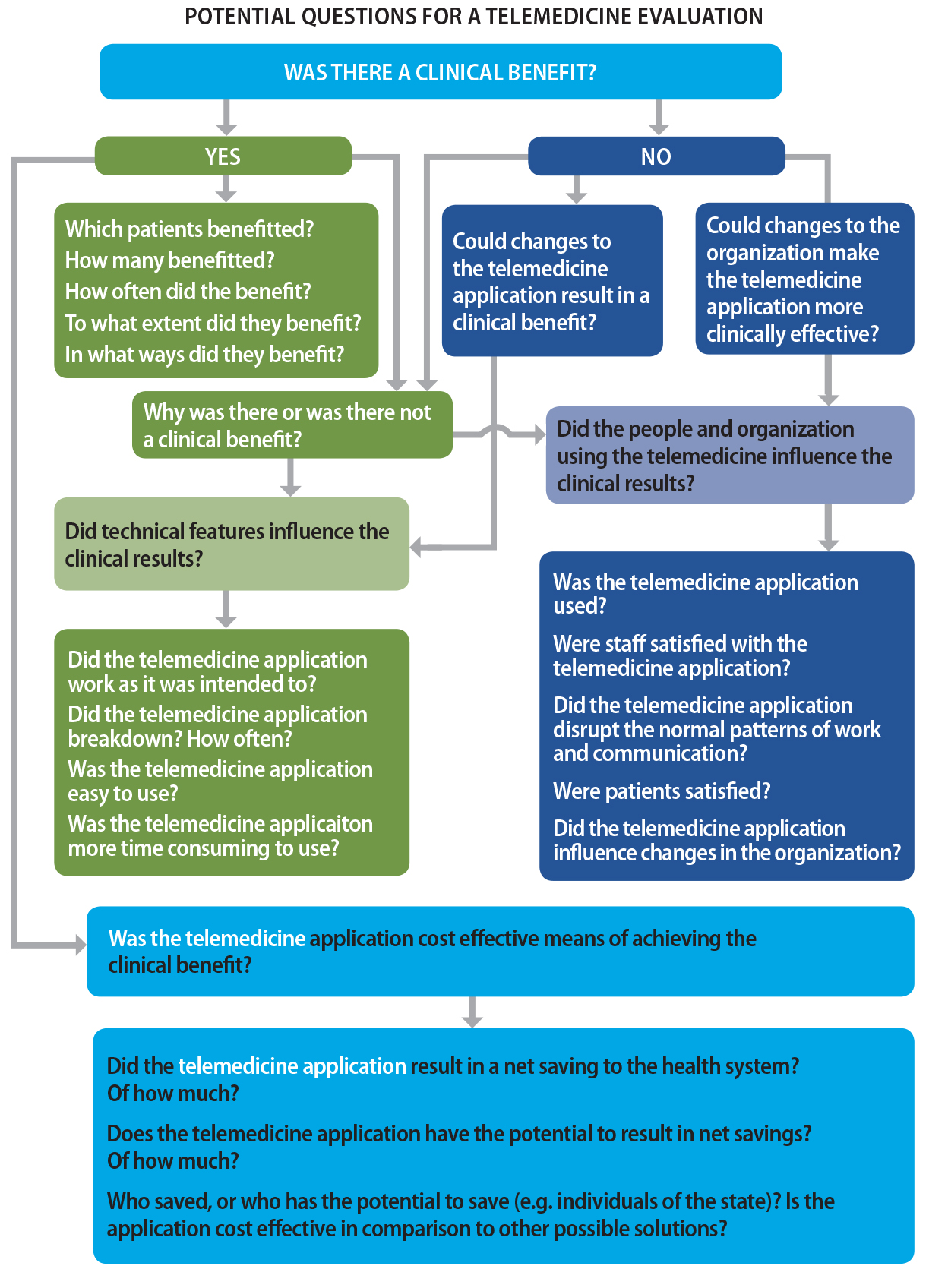

aspects, which Brear (2006) has typified as determining clinical benefits, causal influences from technical, people and organizational factors, and cost-effectiveness in terms of obtaining the benefits (see Figure 25.1 below).

Alternatively, approaches to evaluation can be derived through synthesis, by

identifying key groupings of evaluation elements from reviews of studies of a

number of comparable interventions. Ekeland, Bowes, and Flottorp (2010)

reviewed a wide range of studies offering evidence of clinical effectiveness

and itemized major evaluation elements as behavioural, cost/economic, health, organizational, perception/satisfaction,

quality of life, safety, social, and technology. Deshpande and colleagues (2009) reviewed store-and-forward interventions and

summarized the main evaluation elements in four categories: health outcomes, process of care, resource utilization and user satisfaction. Wade, Kanon, Elshaug, and Hiller (2010) considered economic analyses of

telehealth services, and determined that evaluation elements could be grouped

as costs and effects, technology, and organizational aspects.

Figure 25.1. Clinically focused evaluation strategy.

Note.From “Evaluating telemedicine: lessons and challenges,” by M. Brear, 2006, The Health Information Management Journal (Australia), 35(2), p. 25. Copyright 2006 by SAGE Publications, Ltd. Reprinted with permission.

Recently a collaborative European proposal has been developed for a

comprehensive Model for Assessment of Telemedicine Applications (MAST) (Kidholm et al., 2012) which provides a wide scope of synthesis by addressing

seven distinctive evaluation domains: health problem and application, safety, clinical effectiveness, patient

perspectives, economic approach, organizational aspects, and socio-cultural/ethical/legal aspects. It is recommended that these be analysed in a three-step approach, covering preceding considerations, multidisciplinary assessment, and transferability assessment. This possibly is the most extensive example of a synthesis approach and has

yet to see widespread adoption.

25.3.1 Telehealth Evaluation Frameworks

Evaluation frameworks have been developed to provide a higher-level contextual

setting for selection, or aggregation, of the above diverse elements. An

evaluation framework consists of categories containing different evaluation

questions or objectives, from which an evaluator might choose those most

pertinent to the intervention. A strong argument in favour of framework

approaches is that ad hoc choices of evaluation elements can lead to selection

(or, alternatively, omission) of measures which are strongly correlated with

the success (or failure) of interventions (Jackson & McClean, 2012).

Some early framework concepts followed a sequential set of considerations

related to the telehealth intervention: Hebert (2001) proposed three areas of

focus for evaluation: structure, process and outcomes. Bashshur et al. (2005) advocated a refined version of this approach with high

level sequential structuring of evaluation aspects in four time steps: evaluability assessment to identify what could or could not be evaluated based on the description and

scope of the intervention project; documentation evaluation (including artefacts such as software) for the intervention design and

implementation; then applying formative or process evaluation for the change and acceptance associated with deployment of the intervention in

a clinical service; and finally summative or outcome evaluation applicable to health and economic benefits.

Taxonomies of telehealth are useful for identifying and grouping elements, which

may be candidates for evaluation, in different circumstances. Tulu, Chatterjee,

and Maheshwari (2007) defined a structural taxonomy based on the components

that must be used in the realization of a service, namely application purpose, application area, environmental setting, communication

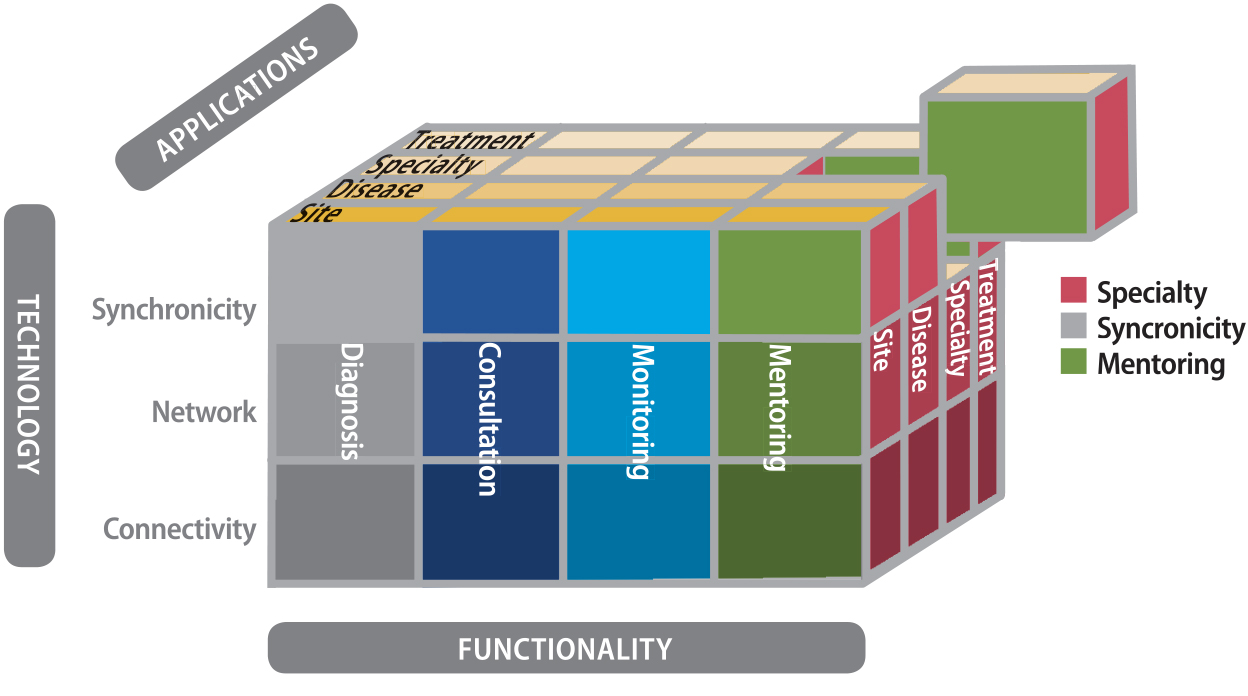

infrastructure, and delivery options. More recently, Bashshur, Shannon, Krupinski, and Grigsby (2011) advanced a

more top-down approach via conceptualization as a three dimensional space

describing intersection sets of functionality, application and technology elements (see Figure 25.2). Nepal, Li, Jang-Jaccard, and Alem (2014) proposed a

framework of broader coverage, including six aspects for evaluation: health domains, health services, delivery technologies, communication

infrastructure, environment setting, and socio-economic analysis.

Alternative approaches to evaluation frameworks have emerged recently in an

attempt to provide greater inclusivity and flexibility, as those described

above tend to focus on abstract concepts to define them. Van Dyk (2014)

reviewed possible areas for evaluation based on technology development models,

and proposed a multi-dimensional space associated with technology maturity principles and systems life cycle concepts. A hybrid approach was proposed by Maeder, Gray, Borda, Poultney, and

Basilakis (2015) as a means of aligning evaluation with organizational learning models and health system performance indicators. Such frameworks as these offer comprehensive coverage and useful mechanisms

for describing evaluation instances (especially those pertinent to large-scale

projects or services), but add conceptual complexity that cannot be easily

navigated for simpler telehealth implementations.

Figure 25.2. Top-down taxonomy.

Note. From “The taxonomy of telemedicine,” by R. Bashshur, G. Shannon, E. Krupinski, and J. Grigsby, 2011, Telemedicine and e-Health, 17(6), p. 491. Copyright 2011 by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Publishers.

25.3.2 Telehealth Evaluation Practice

The lack of consensus on evaluation methodologies for telehealth is largely a

consequence of the complexity of telehealth interventions. Many of the

frameworks discussed so far represent attempts to map this complexity onto

evaluation methodologies, whose aim is to measure the impact and efficacy of a

telehealth intervention. The “gold standard” in the evaluation of medical interventions is the randomized controlled trial (RCT), which tends to be applied to an intervention as a self-standing analysis,

without catering for the effects of contextual complexity.

There are many reasons why such a trial is not usually feasible in telehealth

(Agboola, Hale, Masters, Kvedar, & Jethwani, 2014), including the inability to conceal from participants the

assignment of subjects into control or intervention groups. The complexity and

expense of RCTs limits their application to small, short-term projects. There is also an

ethical issue of denying control groups access to apparently beneficial

technologies, when the aim of the evaluation might be to assess the

cost-effectiveness of an intervention whose clinical benefit might not be in

dispute (Bonell, Fletcher, Morton, Lorenc, & Moore, 2012). Furthermore, there is a need in telehealth evaluations to

investigate not only the change in clinical outcomes, but also the mechanisms

underlying such changes. Such mechanisms should ideally be studied

individually, as well as through their combined impacts on clinical outcomes. RCTs are not capable of such things as assessing the separate effects of

intervention components or of discovering hidden explanations for the success

or otherwise of interventions (Marchal et al., 2013).

A major telehealth evaluation exercise using cluster randomized trial

methodology was conducted as part of the United Kingdom-based Whole Systems

Demonstrator (WSD) project, seeking to validate the effects of home telecare on a range of

clinical aspects including mortality, hospital admissions, use of care, quality

of life, etc. (Steventon, Bardsley, & Billings, 2012). This provides a good example of the pros and cons of the

randomized trial approach. While a high strength of evidence was obtained by

sample sizes in the range of thousands, many of the findings did not show major

gains for telehealth and it has been suggested that such large-scale trials may

be subject to systematic bias due to their health system context (Greenhalgh,

2012).

A feature of RCTs is the separation of experimenters and participants; a double-blind trial is

administered by clinicians who are unaware of which group (control or

intervention) subjects belong to. As pointed out above, such methodologies

produce rigorous verifiable measures, but might not capture the benefits and

mechanisms of complex medical interventions such as telehealth. A growing trend

is to reduce the isolation of researchers and subjects, with benefits to both

assessing the benefits of interventions, and to more widespread implementation

of such interventions. For example, in a wide-ranging review of participatory

research by Jagosh and colleagues (2012), it was concluded that “multi-stakeholder co-governance can be beneficial to research contexts,

processes, and outcomes in both intended and unintended ways”.

It is clear from the preceding that telehealth is among the more complex medical

interventions and, accordingly, evaluation of telehealth systems cannot adopt

methodologies that might be appropriate for, say, a pharmaceutical trial.

Increasingly, telehealth projects are assessed by methods in which a large

number of stakeholders contribute to the process, and the underlying research

questions go beyond simple measures of clinical effectiveness. It has been

noted (Gagnon & Scott, 2005) that telehealth evaluation often serves different purposes for

different stakeholders, so it might be expected that no single evaluation

framework or methodology can cater comprehensively for it.

This complex environment may be best approached by a participatory strategy for

evaluation, involving stakeholders in study designs. Translation of evaluation

findings and evidence to influence policy is a further challenge, as

policy-makers are typically difficult to engage as stakeholders in long-term

studies; nevertheless, the power of case studies to connect back to them has

been demonstrated (e.g., Jennett et al., 2004). The question of responsiveness

and insight by policy-makers in response to the provision of evaluation

findings and evidence has been raised (Doarn et al., 2014) and it is argued

that policy formulation might be included as a stage of any overall evaluation.

25.4 Case Study: Evaluation Using Participatory Principles

Chang (2015) identified five stages in the cycle of telehealth implementation: inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impact. However, in practical telehealth implementations, the early stages of the

project (system design, stakeholder analysis) are often separated from other

processes, mainly through such restraints as the need to use off-the-shelf

hardware, or interoperability issues outside the scope of the project, or the

difficulty of involving all stakeholders in the study. In cases where

participants are able to contribute to technology design, such participatory

methods have been shown to contribute to the success of telehealth systems (Li

et al., 2006).

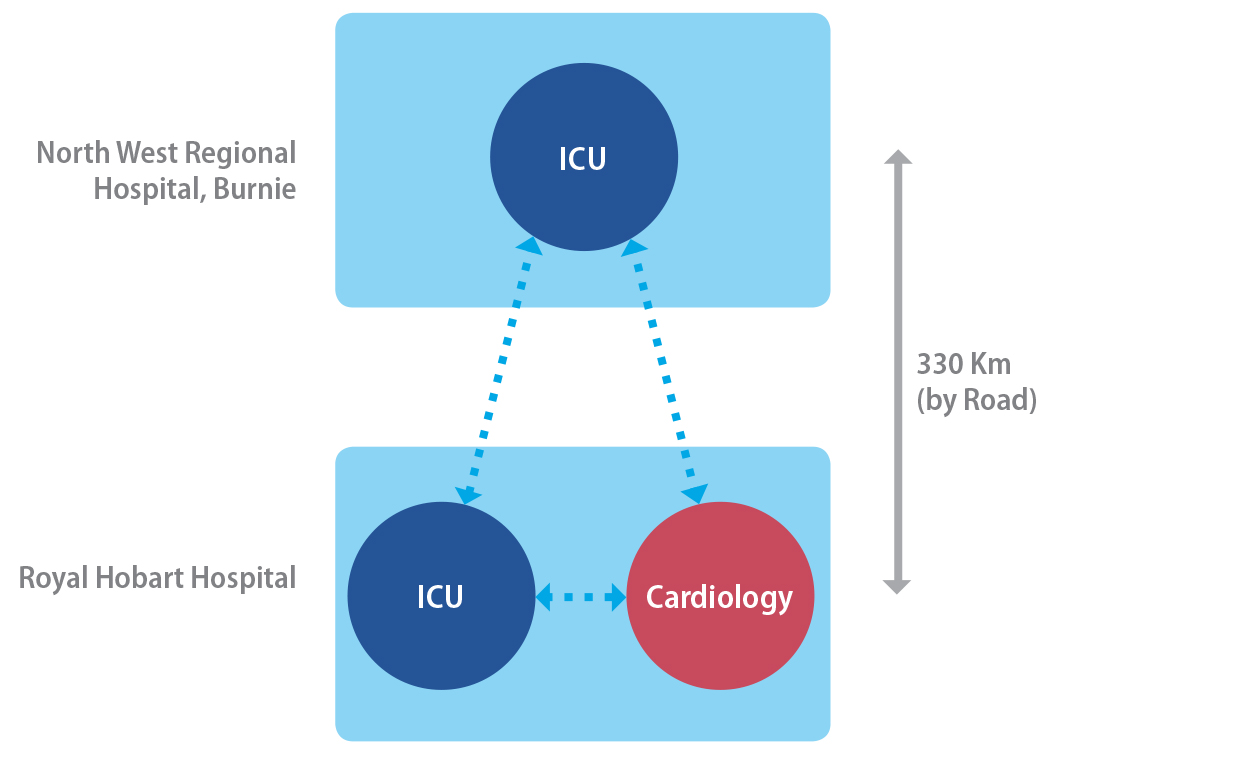

Figure 25.3. Telehealth connectivity for the case study project.

Note. From “Applying an integrated approach to the design, implementation and evaluation of

a telemedicine system,” by S. Hansen, L. Wilson, and T. Robertson, 2013, Journal of the International Society for Telemedicine and eHealth, 1(1), p. 21. Copyright 2013 by ISFTEH. CC BY License.

An example of a telehealth implementation, which incorporates aspects of

participatory design and participatory research/evaluation, was the ECHONET project in Australia described by Hansen, Wilson, and Robertson (2013). Its

principal aim was to support the Intensive Care Unit of North West Regional

Hospital (NWRH) located in Burnie, North Western Tasmania. This ICU had basic intensivist coverage, but relied on other hospitals, and

predominantly a major tertiary hospital Royal Hobart Hospital (RHH), for support in other specialist services, notably bedside echocardiography

(see Figure 25.3). In this project, three mobile multichannel broadband

telemedicine units connected, over a broadband network, the ICU of NWRH with separate nodes in two departments (Cardiology and ICU) of RHH. The aim was not to provide a fully outsourced intensivist service, the

suggested model for some recent eICU implementations (Goran, 2012), but to provide support for the small, isolated

specialist staff at NWRH.

A combination of a participatory research philosophy and learnings from the team’s previous experience with telemedicine systems (Wilson, Stevenson, & Cregan, 2009) influenced the approach. It was agreed from the beginning that an

integrated design, implementation and evaluation approach would be adopted.

Underpinning the practice of participatory research is an intention of the

researcher to effect positive change on the situation within which the research

is taking place while simultaneously conducting research, and a collaborative

approach between the researcher and subject in reaching this objective and

developing understanding.

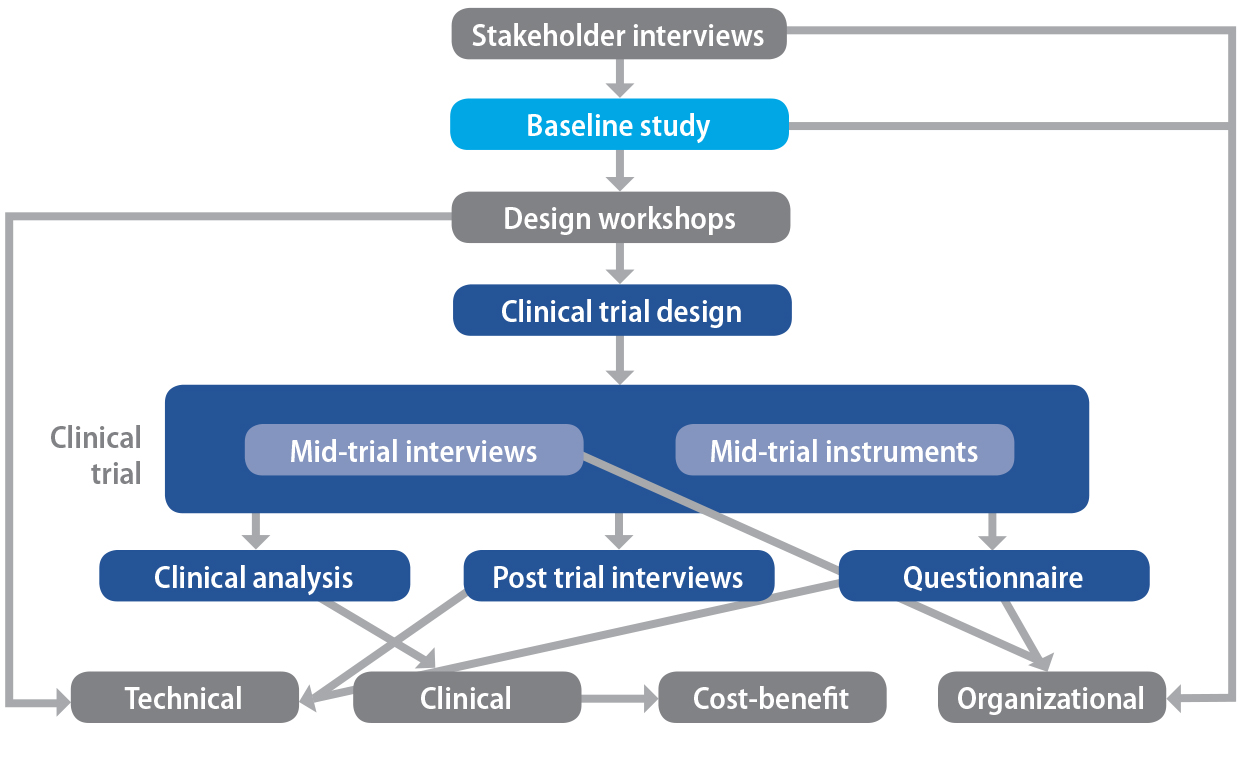

Activities were carried out in the ECHONET project that informed the design of the system, the implementation strategy

adopted, and the criteria assessed in the evaluation. These activities

consisted of stakeholder interviews, baseline study, design workshops, and activities relating directly to the clinical trial of ECHONET including interviews, questionnaires and logbooks. In detail, these activities were as follows:

- The stakeholder interviews helped to establish the success criteria by which the system was assessed in the evaluation phase. They also served to inform the design workshops by establishing potential applications outside the design brief.

- The baseline study provided a datum on which changes might be captured as a result of the implementation and provided the project team with an understanding of the context and environment in which ECHONET would be used, including clinicians’ existing work practices.

- Several design workshops were carried out with mock-ups of the graphical user interface (GUI) and as early prototypes became available, enabling the project to capture the benefits of user-centred design as described by Sutcliffe et al. (2010).

- Instruments deployed during the trial included weekly interviews with all users, logbooks, and a series of mid-trial interviews to monitor the trial for possible modifications, and to refine the end-of-trial processes. Post-trial instruments consisted of interviews with participants, a questionnaire for all participants and an analysis of the nature and frequency of all system activations.

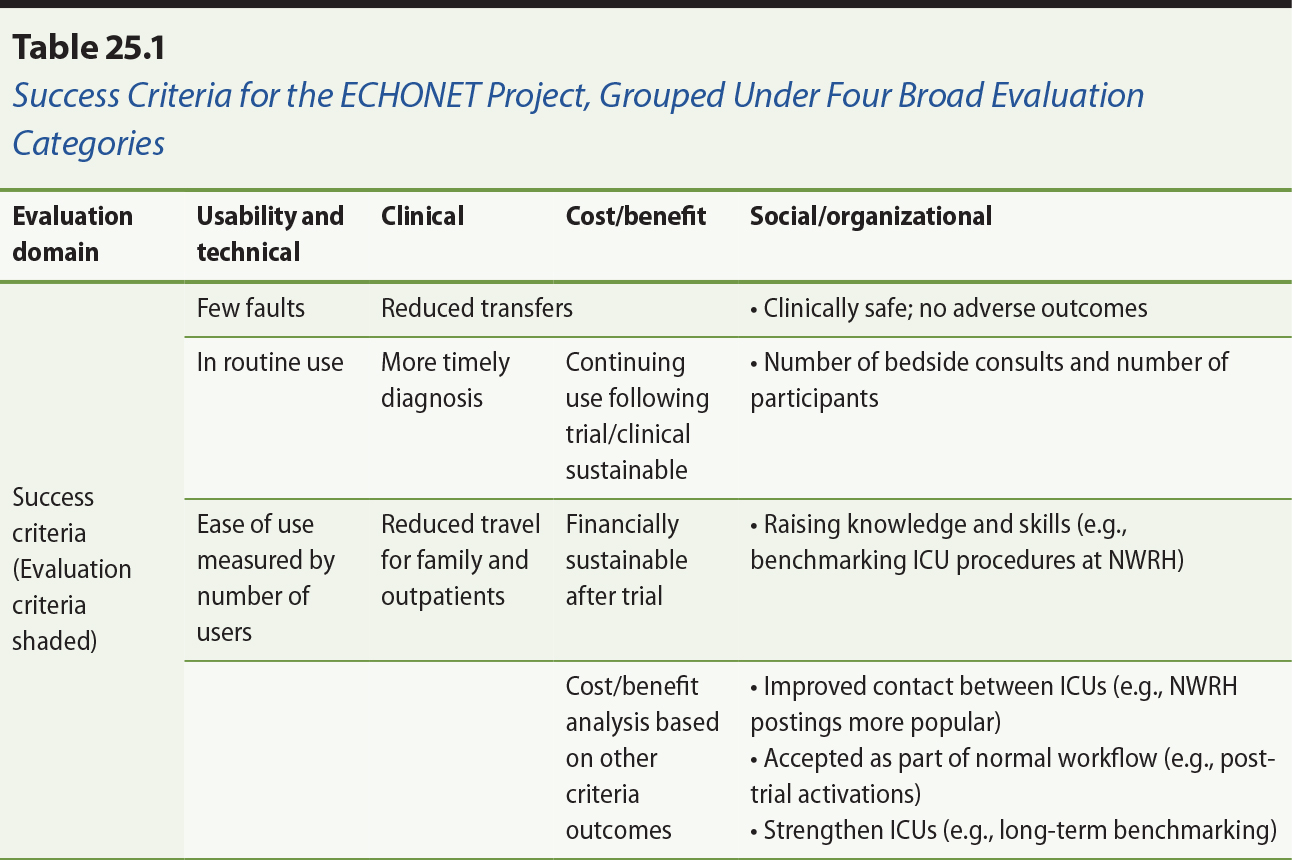

These activities resulted in a list of success criteria, against which the

success of the trial could be assessed, and were grouped under four broad

categories of technical success, clinical efficacy, cost-benefit, and

social/organizational. These criteria, described in detail by Hansen et al.

(2013), differed markedly from those envisaged before the interactive process

described above, and formed the basis of the final evaluation. While improved

clinical outcomes are usually regarded as the primary benefit of telemedicine

systems, in this case clinically driven activations of the system proved to be

a relatively minor application, and the trial yielded too few such activations

in any particular clinical category to achieve statistical significance. The

way in which the success criteria were themselves outcomes of the combined

process is shown in Figure 25.4, in which the vertical axis represents

approximately a time axis.

Figure 25.4. Components of the ECHONET project.

Note. From “Applying an integrated approach to the design, implementation and evaluation of

a telemedicine system,” by S. Hansen, L. Wilson, and T. Robertson, 2013, Journal of the International Society for Telemedicine and eHealth, 1(1), p. 27. Copyright 2013 by ISFTEH. CC BY License.

The success criteria and the measurable outcomes have been tabulated in Table

25.1. They are grouped as relating to the four broad categories of

usability/technical, clinical, cost/benefit and organizational. Clinical

benefits were difficult to quantify due to the diversity of clinical

applications, but the validity of the technical solution was verified, and a

range of social/organizational benefits were demonstrated, mainly among

improved collegiate and educational interactions among the three participating

sites.

It is clear from Table 25.1 that most of the perceived benefits were in the

social/organizational area. However, the principal outcome of the project was a

verification of the methodology of integrating design, implementation and

evaluation processes. Many of the benefits were not envisaged at the beginning

of the project, and the adaptive nature of the evaluation process ensured that

these benefits could be assessed.

The most significant outcomes centred around improved collegiate relationships

and educational opportunities among the users. Participants, in both the

interviews and questionnaires, were very positive about the usability and

usefulness of ECHONET, with some minor technical reservations. While all participants agreed that

there were strong clinical benefits, the data sample was too small and diverse

for this to be quantified by this study.

While the benefits of the collaboration supported by ECHONET for clinicians in the more remote hospital site at NWRH were more obvious and expected, clinicians in Hobart also recognized they had

benefited from the collaborations made possible by the new technology. The

educational benefits of ECHONET were realized early in the clinical trial. Education represents a good area in

which to start using new telemedicine systems as sessions can be scheduled to

allow familiarization with the system in a relatively low-pressure situation

and routine use. The potential for ECHONET to be used for this purpose emerged early and strongly during the baseline study

and this potential was confirmed and further explored during the clinical trial

by clinicians at both hospitals.

25.5 Summary

This chapter has presented a view that Telehealth may be regarded as a “special case” in eHealth evaluation, in that it difficult to treat its components in

isolation from the context of usage. Nevertheless, typical telehealth

evaluations tend to have focused on selected areas which include costs and

resources, organizational and social aspects, and clinical benefits, rather

than comprehensive coverage. Attempts to identify various sets of criteria,

models and frameworks for evaluation have been described in the literature

without achieving widespread consensus. These have been based around such

disparate views as the inherent sequential characterization of a Telehealth

intervention over time, or the taxonomic analysis of Telehealth along system

functionality lines. It is argued that there is an overarching need to take a

holistic approach and integrate different elements of evaluation to understand

characteristics of the overall system of interest which is enabled by

Telehealth. A case study has been presented to illustrate this process,

borrowing from the central paradigm of participatory research as the holistic

mechanism. This example was not intended to be definitive or exclude other

approaches, but to emphasize the power of multifactor evaluations in such

settings.

References

Agboola, S., Hale, T. M., Masters, C., Kvedar, J., & Jethwani, K. (2014). “Real-world” practical evaluation strategies: A review of telehealth evaluation. JMIR Research Protocols, 3(4), e75.

Bashshur, R. L. (1995). On the definition and evaluation of telemedicine. Telemedicine Journal, 1(1), 19–30.

Bashshur, R., Shannon, G., & Sapci, H. (2005). Telemedicine evaluation. Telemedicine and e-Health, 11(3), 296–316.

Bashshur, R., Shannon, G., Krupinski, E., & Grigsby, J. (2011). The taxonomy of telemedicine. Telemedicine and e-Health, 17(6), 484–494.

Bonell, C., Fletcher, A., Morton, M., Lorenc, T., & Moore, L. (2012). Realist randomised controlled trials: A new approach to

evaluating complex public health interventions. Social Science and Medicine, 75(12), 2299–2306.

Brear, M. (2006). Evaluating telemedicine: lessons and challenges. The Health Information Management Journal (Australia), 35(2), 23–31. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18209220

Chang, H. (2015). Evaluation framework for telemedicine using the logical

framework approach and a fishbone diagram. Healthcare Informatics Research, 21(4), 230–238.

Doarn, C. R., Pruitt, S., Jacobs, J., Harris, Y., Bott, D. M., Riley, W., Lamer,

C., & Oliver, A. L. (2014). Federal efforts to define and advance telehealth — A work in progress. Telemedicine and e-Health, 20(5), 409–418.

Clarke, M., & Thiyagarajan, C. A. (2008). A systematic review of technical evaluation in

telemedicine systems. Telemedicine and e-Health, 14(2), 170–183.

Deshpande, A., Khoija, S., Lorca, J., McKibbon, A., Rizo, C., Husereau, D., & Jadad, A. J. (2009). Asynchronous telehealth: a scoping review of analytic

studies. Open Medicine, 3(2), 69–91.

Ekeland, A. G., Bowes, A. S., & Flottorp, S. (2010). Effectiveness of telemedicine: A systematic review of

reviews. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 79(11), 736–771.

Gagnon, M.-P., & Scott, R. E. (2005). Striving for evidence in e-health evaluation: lessons from

health technology assessment. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 11(suppl 2), 34–36.

Goran, S. F. (2012). Measuring tele-ICU impact: Does it optimize quality outcomes for the critically ill patient? Journal of Nursing Management, 20(3), 414–428.

Greenhalgh, T. (2012). Whole System Demonstrator trial: Policy, politics and

publication ethics. British Medical Journal, 345, e5280.

Hailey, D., Jacobs, P., Simpson, J., & Doze, S. (1999). An assessment framework for telemedicine applications. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 5(3), 162–170.

Hansen, S., Wilson, L., & Robertson, T. (2013). Applying an integrated approach to the design,

implementation and evaluation of a telemedicine system. Journal of the International Society for Telemedicine and eHealth, 1(1), 19–29.

Hebert, M. (2001). Telehealth success: Evaluation framework development. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics,84(2), 1145–1149.

Heinzelmann, P. J., Williams, C. M., Lugn, N. E., & Kvedar, J. C. (2005). Clinical outcomes associated with

telemedicine/telehealth. Telemedicine and eHealth, 11(3), 329–347.

Hersch, W., Helfand, M., Wallace, J., Kraemer, D., Patterson, P., Shapiro, S., & Greenlick, M. (2002). A systematic review of the efficacy of telemedicine for

making diagnostic and management decisions. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 8(4), 197–209.

Hersch, W. R., Hickham, D. H., Severance, S. M., Dana, T. L., Pyle Krages, K., & Helfand, M. (2006). Diagnosis, access and outcomes: Update of a systematic

review of telemedicine services. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 12(suppl 2), 3–31.

Jackson, D. E., & McClean, S. I. (2012). Trends in telemedicine assessment indicate neglect of

key criteria for predicting success. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 26(4), 508–523.

Jagosh, J., Macaulay, A. C., Pluye, P., Salsberg, J., Bush, P. L., Henderson,

J., ... Greenhalgh, T. (2012). Uncovering the benefits of participatory

research: Implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Quarterly, 90(2), 311–346.

Jennett, P. A., Scott, R. E., Affleck Hall, L., Hailey, D., Ohinmaa, A.,

Anderson, C., … Lorenzetti, D. (2004). Policy implications associated with the socioeconomic

and health system impact of telehealth: A case study from Canada. Telemedicine and e-Health, 10(1), 77–83.

Kidholm, K., Ekeland, A. G., Jensen, L. K., Rasmussen, J., Pedersen, C. D.,

Bowes, A., Flottorp, S. A., & Bech, M. (2012). A model for assessment of telemedicine applications: MAST. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 28(1), 44–51.

Li, J., Wilson, L. S., Percival, T., Krumm-Heller, A., Stapleton, S., & Cregan, P. (2006). Development of a broadband telehealth system for critical

care: Process and lessons learned. Telemedicine and e-Health, 12(5), 552–561.

Maeder, A., Gray, K., Borda, A., Poultney, N., & Basilakis, J. (2015). Achieving greater consistency in telehealth project

evaluations to improve organizational learning. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 209, 84–94.

Marchal, B., Westhorp, G., Wong, G., Van Belle, S., Greenhalgh, T., Kegels, G., & Pawson, R. (2013). Realist RCTs of complex interventions – an oxymoron. Social Science and Medicine, 94(1), 124–128.

Nepal, S., Li, J., Jang-Jaccard, J., & Alem, L. (2014). A framework for telehealth program evaluation. Telemedicine and e-Health, 20(4), 393–404.

Scott, R. E., McCarthy, F. G., Jennett, P. A., Perverseff, T., Lorenzetti, D.,

Saeed, A., Rush, B., & Yeo, M. (2007). National telehealth outcome indicators project. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 13(suppl 2), 1–38.

Stamm, B. H., & Perednia, D. A. (2000). Evaluating psychosocial aspects of telemedicine and

telehealth systems. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31(2), 184–189.

Steventon, A., Bardsley, M., Billings, J., Dixon, J., Doll, H., Hirani, S., … Newman, S., for the Whole System Demonstrator Evaluation Team. (2012). Effect

of telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality: Findings from the Whole

System Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. British Medical Journal, 344, e3874.

Sutcliffe, A., Thew, S., De Bruijn, O., Buchan, I., Jarvis, P., McNaught, J., & Proctor, R. (2010). User engagement by user-centred design in e-Health. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. Mathematical, Physical and

Engineering Sciences, 368(1926), 4209–4224.

Tulu, B., Chatterjee, S., & Maheshwari, M. (2007). Telemedicine taxonomy: a classification tool. Telemedicine and e-Health, 13(3), 349–358.

Van Dyk, L. (2014). A review of telehealth service implementation frameworks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(2), 1279–1298.

Wade, V. A., Kanon, J., Elshaug, A. G., & Hiller, J. E. (2010). A systematic review of economic analyses of telehealth

services using real time video communication. BMC Health Services Research, 10, 233.

Wilson, L. S., Stevenson, D. R., & Cregan, P. (2009). Telehealth on advanced networks. Telemedicine and e-Health, 16(1), 69–79.

Wootton, R., & Hebert, M. A. (2001). What constitutes success in telehealth? Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 7(suppl 2), 3–7.

Annotate

EPUB